The Los Angeles County district attorney filed charges in August against a former Santa Clarita assistant city engineer who allegedly redirected to his own account more than a half-million dollars in refunds of cash payments in lieu of bonds from contractors, engineers and others that performed services for the city.

David Rubira was originally arrested in May but many details of his alleged crimes had not previously been disclosed. City of Santa Clarita officials say they will seek restitution as well as making a claim under an employee-fraud insurance policy with a $1 million limit.

According to a city statement made at the time of Rubira's arrest, he "admitted to the crimes during questioning."

A preliminary hearing in the county’s case against Rubira will occur September 30. If Rubira is convicted without a special plea agreement, he faces 13 years and eight months in state prison.

Exactly what plea Rubira will make and what penalty may follow is unclear. And it is unclear whether the city can collect the full amount under its fraud insurance policy. The name of the insurer was not released.

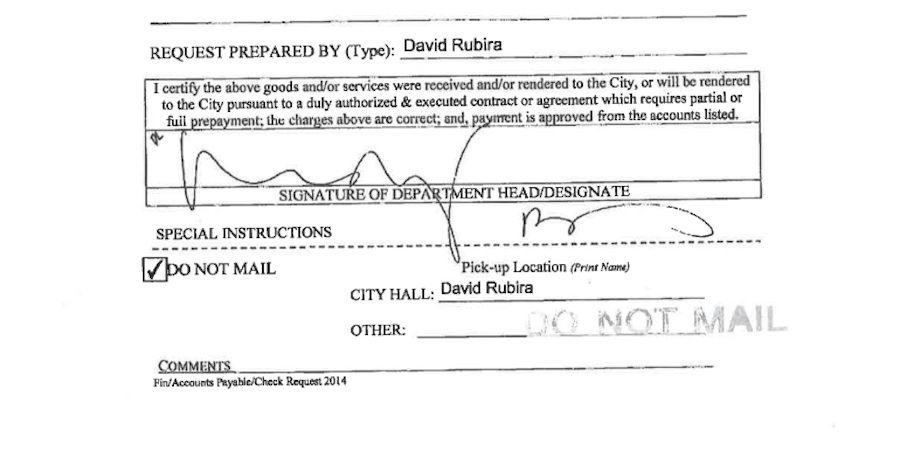

At the time of the initial arrest, the city stated that Rubira oversaw developer funds deposited as part of the permit entitlement process and held pending completion of the developers' work on city project. After finishing their work, developers requested refunds. "Rubira appears to have manipulated city documents/paperwork to avoid detection and perpetrate the fraud," city officials said in a statement.

More is known about the alleged crimes now. The county district attorney’s office said in a press release that from November 2012 to April 2015, Rubira embezzled $533,571 in 58 check payments to himself. The incident caused Santa Clarita officials to hire investigators to identify what factors allowed the embezzlement to go unnoticed for so long, and how to prevent it from happening again.

The money came from the city of Santa Clarita’s program to accept cash in lieu of bonds from companies doing any kind of permitted work in the city. When the work is complete, the cash is usually returned to the development companies or contractors who made the deposits. The district attorney alleges that Rubira instead issued the refunds to bank accounts he opened using names very similar to the intended refund recipients.

Few Prevention Measures in Place

According to the audit by KPMG US LLP, Rubira volunteered to work through a backlog of refunds to contractors for the city’s Development Services office. The audit claims that he was able to make the check payments to himself because he left few traces of communications about his work, changed vendor details in the invoicing system without oversight and circumvented controls intended to ensure that checks were mailed to the appropriate addresses.

The KPMG investigators believe that Rubira worked alone.

The KPMG audit states that Rubira used seven vendor names to issue the checks, which he deposited in five bank accounts he controlled. The firms whose names Rubira allegedly emulated include a commercial development company and several engineering and design firms.

Gail Morgan, public information officer for the Santa Clarita city manager’s office, says that the projects related to the refunds were almost all for public works.

Rubira worked for the city of Santa Clarita for eight years, and was terminated after his arrest in May. He was not a licensed engineer.

Cash in Lieu of Bonds

The city of Santa Clarita accepts cash in lieu of bonds from anyone seeking a permit to do work in the city, as a guarantee that the work will be completed.

For projects owned by the city, it requires a faithful performance bond and a labor and material bond, each for the complete contract amount. Contractors submitting bids to the city are also expected to submit a bid bond for 10% of the contract amount, which can take the form of a certified or cashier’s check returned when the city council awards the contract. Santa Clarita does not accept cash in lieu of these requirements for its own projects, says Morgan.

The cash-in-lieu-of-bonds program is a response to state regulations, she says.

“The State Code requires security for improvements and obligations at time of map recordation, so our program is similar to other Cities," says Morgan. "The revised release program is much more comprehensive than most.”

Revisions to the refund release program suggested in the KPMG audit include more thorough procedures for changing recorded vendor data, proactive vendor information updates and check refunds, more checks and balances throughout the process of issuing refunds, regular reviews, surprise audits, and regularly changing who is responsible for refunds.