While the Tideway super sewer project, following the River Thames through the heart of London, is a British endeavor, the contracting team is very multinational. Even though the United Kingdom is preparing to leave the European Union, contractors from France, Spain and the Netherlands, backed by European Union financing, are helping to drive the U.K.’s biggest water project, being built to comply with EU law.

The first of five German and French-made tunnel boring machines set off on its stretch of the super sewer in November. With its diameter varying from 6.5 meters to 7.2 m, the Tideway Tunnel will run from Acton in the west to Abbey Mills, sloping down at a 1:800 incline and reaching about 65 m below ground at its deepest point.

When it goes into operation in about 2024, the tunnel will divert discharges from 34 combined sewer overflow (CSO) points, eliminating more than 90% of the annual amount of raw sewage that enters the river, as high as 39 million tonnes some years.

With around $2 billion worth of design and construction completed along the riverside tunnel route, three design-build contractors have now mobilized 20 of 21 sites and are sinking large sewage and machine access shafts to finish the $5.4-billion job.

Brexit will end the free movement of EU workers into the U.K. “The question is whether [London] is still an attractive place for people to stay and work.”

– Nick Bertram, McKinsey & Company

Under a $530-million contract, the joint venture of Dutch-owned BAM Nuttall Ltd. with Morgan Sindall Plc. and Balfour Beatty Group Ltd. is preparing to drive 6 kilometers west from Acton to the Carnwath shaft, including the 1.1-km Frogmore drive from Carnwath south to a CSO in Wandsworth. To the east, Spain’s Ferrovial Agroman U.K. Ltd., with Laing O’Rourke Construction, is handling the 12.7-km central contract between Carnwath and Chambers Wharf, signed for $950 million. Ferrovial subsidiary Amey Plc. has a separate system integration contract. Paris-based Vinci Construction Grands Projects and its affiliate Bachy Soletanche with Costain Ltd. have the $770-million, 5.5-km contract from Chambers Wharf to Abbey Mills. A 4.6-km link to Greenwich is part of the contract. Vinci also led the earlier team that built the 6.9-km Lee tunnel from Abbey Mills, completed in 2016, which will deliver Tideway’s flow for treatment at the large wastewater plant in Beckton.

The contractors were lured by the super sewer project at a time when heavy construction on the Lee tunnel and London’s vast Crossrail system was nearing completion, creating spare capacity around 2014, says Andy Alder, the owner’s program delivery director. “There was a lot of interest and a lot of capability built up in London,” he says. International bidders are drawn to the U.K. by work that is often packaged in bigger contracts than elsewhere in Europe, leading to more competitive bids, says Nick Bertram, an associate partner with the management consultant McKinsey & Company. France, for example, bids about 10 times more projects for the same total value of work, he says.

But, warns Bertram, that competitive advantage risks being eroded by Brexit’s termination of the free movement of EU workers into the U.K. “The question is whether [London] is still an attractive place for people to stay and work,” he says. With some projects employing 50% EU workers, “in London, it’s a serious issue.” In recruitment terms, that could challenge Tideway, which is expected to create 4,000 jobs directly and 5,000 more indirectly.

Because contractors need to import skills to boost the industry’s productivity, “in a world post-Brexit [that] could well be shut off,” he says. Bertram expects employment uncertainty to last around two years, after which “hopefully we will reach a steady state.”

While regional utility Thames Water developed Tideway and procured it, the tunnel was considered too big for the utility’s balance sheet, so the government and the Office of Water Services, the sector regulator for water, agreed that a private entity would finance, build, own and operate the new infrastructure.

In the summer of 2015, Thames Water procured Bazalgette Tunnel Ltd., a private consortium of financial companies and funds, to own the project, and transferred to it the main design-build contractors it had selected earlier that year.

To attract investors to the inherently risky tunnel venture, the government offered a security package, including a commitment to inject equity to counter cost overruns, as well as insurance indemnities and compensation in case of project termination.

Bazalgette committed more than $1.5 billion in equity and shareholder loans to the project, and also raised bonds and commercial debt. The EU’s nonprofit lender, the European Investment Bank, committed an $890-million, 35-year loan, its largest ever in the water sector. Thames Water’s customers will fund repayment of this investment through increased rates.

With this financing, the company will upgrade a sewer system built in the 1860s by the Metropolitan Board of Works, then led by chief engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette. The 1,770-km network of mostly large, egg-shaped sewer tunnels, lined with over 300 million bricks, remains generally in good shape. But it now serves a city with double the original design population of 4 million people.

As the population and per capita water use grew, the CSOs increasingly polluted the river. When the EU’s Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive was finalized by member states in 1991 to clean up Europe’s receiving waters, London CSOs weren’t in compliance.

In 2007, the government endorsed Thames Water’s proposal for a tunnel as the lowest cost option. Alternatives were not investigated with sufficient rigor, according to a review last year by the National Audit Office. But in 2014, the government decided “that delaying the tunnel to consider alternatives further would likely increase the risk of fines for breaching the directive,” according to the auditor.

Nevertheless, refinements to Thames Water’s sewer model allowed the tunnel’s reference design length to be shortened, saving more than $800 million, reports the auditor. This helped offset increasing estimates, which rose to the current official figure of $5.4 billion (in 2016 values) from $2.8 billion. This includes $4.1 billion for construction and related work.

Project Preparation

While still in Thames Water’s hands, from 2012-13 the Tideway team “did a lot of premarketing engagement before going out to [contractor] prequalification,” says Roger Bailey, who is now Bazalgette’s Chief Technical Officer. That helped the team decide on procuring three packages “to get a balance between size and competition,” he adds. The main contracts are design-build with target prices and pain-gain sharing.

After selecting preferred bidders for the main contracts in February 2015, the Thames Water Tideway team initiated a period of optimized contractor involvement as companies were no longer competing. A key focus was determining the best method to form the tunnel’s concrete secondary lining.

With a team of about 70 Bazalgette staff, Bailey’s job is to ensure the project will work correctly and last 120 years. To manage the design, construction and commissioning, Bazalgette hired Jacobs Engineering Group, which is deploying around 200 people, led by program delivery director Andy Alder.

The Tideway team has created a digital version of the River Thames. “We did that because some of the practice and training on the river has been a bit traditional.”

– Roger Bailey, Bazalgette

While builders of the Lee tunnel cast the lining’s crown and invert separately in long formwork, the Tideway work will use full circle, shorter equipment, says Bailey. The Lee project used “huge” pieces of formwork, he adds. They weighed “hundreds of tonnes … very big loads being placed onto the primary lining. Then the loads changed as the shutter got filled up,” he says.

The Tideway team is also trying a novel precast segmental lining, “using a kind of erection and grouting system from a conventional TBM,” says Alder. “The key issue is grouting,” adds Bailey. Grout has to harden quickly enough so that it does not flow out of the open end as the machine advances and be durable enough to last 120 years, he says.

If successful, three or four precast machines will line the central and east sections, reports Alder. Linings for the shorter, smaller west tunnel will be cast in full circle in shorter shutters.

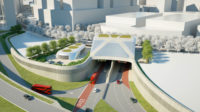

To sink shafts to capture CSO flows and provide tunnelling access, Tideway’s contractors are working at sites along the Thames, reclaiming stretches of river. Seven stretches of the reclaimed river will become public spaces, jutting into the river after construction.

Among them is the central Blackfriars site, which is “probably one of the most complicated,” says John Gullick, the owner’s deputy delivery manager for that section. Structures there will divert the old, covered subterranean River Fleet, which pours over 500,000 cu m of sewage into the river in some years.

The contractor is driving steel king, sheet, tube and bored piles to form the 200-m-long cofferdam, which will extend 40 m from the river bank. Piling started last November, but work has been delayed by the presence of two large utility pipes.

Resulting delays at Blackfriars and at other sites have “substantially eroded available [budget] contingency,” reported Bazalgette recently. Through value engineering and other means, the company hopes to hold to the baseline target cost and schedule.

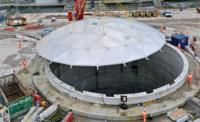

Meanwhile, contractors at the riverside sites are using a range of techniques to sink the project’s 21 shafts, the first of which started June 2017 at Kirtling Street, in Battersea. With internal diameters of up to 30 m, the shafts will be 25 m to 65 m deep, cutting through a range of soil conditions. Shafts at four sites are expected to be completed by the end of the year, with another five under construction.

Located in clay, the Putney shaft, in the west, will be a full-depth gravity sunk caisson. The other western shafts will be excavated and progressively lined with sprayed concrete.

Most central shafts will be started within secant piles or caissons in weaker upper layers, then excavated in good clay with sprayed linings below. Deeper shafts at all the chalky eastern sites, and also Kirtling Street, will be excavated within slurry trench walls. The shaft at Kirtling street, as well as those at Carnwath Road and Chambers Wharf, near London bridge, will provide TBM access.

Three earth pressure balance (EPB) TBMs will drive the west and central stretches, where the ground is clay in the west and then passes through a wet mixture of clays and flinty gravel in the center. A slurry TBM will bore the main tunnel through the eastern chalk.

The first machine, an EPB from France’s NFM Technologies S.A., is now driving the 5-km section from Kirtling Street to Carnwath Road. Its twin TBM will soon start tunnelling 7.6 km east to Chambers Wharf.

From Carnwath Road, a Herrenknecht EPB is due to start its 6 km drive to Acton around March. The same contractor has refurbished a Lovatt EPB for the 1.1-km-long, 2.6-m-dia Frogmore tunnel.

The last big TBM to start, in early 2020, will be a Herrenknecht slurry unit, driving from Chambers Wharf in the east section to Abbey Mills. The same team will use a 5-m-dia slurry Herrenknecht for a 4.6-km link to Greenwich.

As part of its innovation program, Tideway has set up a virtual TBM used for “familiarization of the crews before they start work,” says Alder. “And we’ve used it for reviewing the design [of the TBMs],” he adds.

Another piece of virtual reality is simulating a shaft base, allowing steelfixers to “walk” into their rebar cages. “By bringing them in you’re marrying up the technical visualization with their practical skill, and it’s going to pay off tens of times over,” says Bailey.

The Tideway team has also created “a digital version of the River Thames … where boat crews can validate their competence in a three-to-four-day intensive course,” says Bailey. “We did that because some of the practice and training on the River Thames has been a bit ‘traditional,’ and we felt that as we were in some places potentially tripling the amount of freight movement … we need to make sure that people on our logistics are of the highest level of competence,” he adds.

With the first TBM due to break through in the central section late next year and the last one about two years later in the east, Tideway’s commissioning is expected to start in 2022, says Alder. “Once we start system testing and commissioning, it will get to the point when we will need heavy rainfall to test the system,” he says, so the final completion date is “a little bit in the hands of the weather.”