A distinctive feature of the new $825-million Barclays Center in Brooklyn is its "pre-weathered" facade of rusted steel panels that give the 675,000-sq-ft arena a been-there-all-along air. The unusual curtain wall of the structure, set to open this fall as the home for the National Basketball Association's Nets, has called for pioneering fabrication techniques on a project that has sometimes progressed by trial and error.

The toughened exterior is also a fitting motif for a development that has endured and been shaped by a host of setbacks that included delays, budget cuts, design changes, legal battles and project team overhauls—not to mention a schedule so tight that it kicked off in March 2010 while some residents fighting eviction still lived in a building smack in the middle of the site.

That pockmarked trail, especially the bitter battle with opponents and the development market's collapse, colored many construction and design decisions along the way. Indeed, five years into the planning, developer Forest City Ratner Cos. (FCRC) scrapped an elaborate Frank Gehry design for the arena, which anchors the larger $4.9-billion Atlantic Yards mixed-use development, in favor of the less expensive, more feasible strategy that FCRC handed to Hunt Construction Group, the construction manager.

"Instead of tinkering with the old design, we worked with our team on a smaller, tighter design," says Bob Sanna, director of construction and design development at FCRC, which is the majority partner in a joint venture with Onexim Sports and Entertainment Holding USA to build the center. "We took a radical approach to completing it."

As the hub of a 22-acre, 16-building development that is upending a mostly low-rise retail, residential and industrial district, the arena will be a big new neighbor abutting three of the planned apartment towers in the larger complex that are mostly framed by Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. Barclays and, eventually, the entire Atlantic Yards site are ushering in new infrastructure, including a $72-million upgraded transit station for nine subway lines and a $100-million railyard relocation.

The transit connections, as well as nearby surface parking lots, will funnel visitors to more than 200 events annually, including the 2012-13 season of the Nets franchise, which is relocating from Newark, N.J.

On the inside, the arena's precast concrete seating bowl will host 18,000 basketball fans, with retractable seating for other configurations. The facility has 104 suites on two concourses, six clubs and restaurants, and an onsite practice facility visible to the public.

A major design goal was to integrate the facility into the local bustle. It includes exterior views into the seating bowl, says Stephen Duethman, Midwest region managing principal for AECOM, the lead architect. AECOM partnered on the project with SHoP Architects which, as design architect, developed features such as technology applications that streamlined fabrication and construction of the weathered steel exterior panels.

"The whole dynamic of the interior is based on the industrial and nightlife theme, the feeling of the streets of Brooklyn," Duethman says.

That transparency was a feature of the original design, though little else of that eclectic vision remains other than Gehry's master plan for the Atlantic Yards. "The building had to be transparent and activate the street—not just a big blank wall," Sanna says.

The facility also features an uncommon 80,000-lb capacity elevator and turntable system that will allow trucks to pull in, descend to the sunken event floor for unloading and then be spun around to exit. Crews began pouring concrete footings for the elevator and turntable late last year.

Early Battles

Getting started was an ordeal because Atlantic Yards has been a hotly contested project. It took several years for FCRC to win site development rights. Opponents filed 37 lawsuits, none of which the developer has lost. However, there is one dispute on appeal.

Among the last holdouts trying to stop the arena was Daniel Goldstein, who lived in a condominium building on a Pacific Avenue block that is now part of the site. After seven years as a leading opponent, he left the property after reaching a $3-million settlement, only weeks before a forced eviction in May 2010. He says questions remain about the larger development's impact, particularly thorny parking and traffic issues.

Still, many residents have grudgingly "accepted the arena—it's here," says Letitia James, the district's New York City Council member and a leading opponent. She says traffic and security plans are her main concerns now as the opening nears.

However, FCRC has long contended that Atlantic Yards is rebuilding a "blighted" area and that the arena provides a civic centerpiece and economic engine for the entire borough.

Though it was clear by late 2009 that the courts would let the arena proceed, several buildings that were slated for demolition stood on the footprint well into 2010. "Hunt's team knew they had to work in phases," says Linda Chiarelli, FCRC's deputy director of construction.

Not having full site access for six months led to workflow and schedule changes to design, fabrication, materials shipment and assembly on various parts of the job, says Mark Gladden, project executive for Hunt.

"We also were limited on where we could set up our cranes," Gladden says.

The uneven schedule forced Hunt and its design partners to re-sequence plans for the 10,500 tons of steel it started erecting in November 2010 and topped out last month. The design-assist format helped, though it was new to several local subcontractors and specialty designers, says Ken Johnson, executive vice president for Hunt. "We spent time teaming them up," he adds.

That task was harder still because of the new design's smaller scale and budget than the original Gehry plan, says Jeffrey Fisher, contract manager for Hunt. "A lot of those folks had larger price tags in their heads," he says.

Unlike more common design-build projects, in which designers hand off plans to contractors early on to save time and money, this "design-assist" project has designers staying on board and consulting throughout, Duethman says. "We continued to have a high level of design for the project, and it did not compromise the delivery process," he adds.

It also aided structural designs, says Mike Squarzini, senior principal at Thornton Tomasetti, which coordinated superstructure and facade work throughout the fabrication phases. Working closely with steel suppliers let Thornton adjust its 3D models without losing time or disrupting mill orders. "If the fabricator had framed the facade one way, it could have made for much more load, or if we had designed it another way, it could have made their system too expensive," he says.

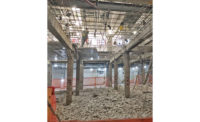

Three cranes and various booms in the main bowl have kept the project humming with tasks such as erecting precast seating, connecting giant free-spanning trusses in sections across eight shoring towers, installing the roof and adding ductwork, Chiarelli says.

The team also progressed on the facade, despite a hiccup in December 2011 when the Indiana-based panel fabricator ASI Limited shut down due to financial problems. Hunt helped to reopen the operation a few weeks later.

The exterior will include a contoured canopy with a giant open oval in the middle that cantilevers more than 80 ft from the main Atlantic Avenue entrance toward the subway station. The canopy will sport materials similar to the main glass-and-steel curtain wall.

Each of the facade's roughly 12,000 uniquely shaped steel pieces is going through 1,050 wet-and-dry cycles across an 88-day cycle to create a rust layer that acts as a protective, hardened shell. The fabricator is pre-setting pieces into about 1,000 larger units that crews install on site.

Using rainwater and humidity and temperature controls to perfect the rusting effect hit snags that required further tweaking, Chiarelli says.