Best Overall Project/Best Sports and Entertainment: Barclays Center

To build an 18,100-seat arena, it's best to avoid certain obstacles. One is choosing a property at the busiest intersection of a borough with 2.5 million people. Another is breaking ground before settling ownership disputes over large chunks of the site. One more is making big design changes after basic structural engineering features are set in place.

Any of these hurdles—not to mention a superstorm, multiple legal challenges and a key team member's default—could have derailed completion of Brooklyn's 675,000-sq-ft Barclays Center. Instead, the $1-billion arena developed by Forest City Ratner Cos. (FCRC) opened on time last fall without cost overruns and quickly became a new civic hub, hosting more than 200 events, including concerts and home games for the National Basketball Association's Nets and National Hockey League's Islanders.

It was this sizable project's success in the face of such challenges, coupled with the arena's immediate impact, that captured the 2013 Best Projects judging panel's attention and, ultimately, its unanimous vote for the tristate region's project of the year.

"It certainly enhanced the community and provided a lot of opportunities in terms of employment both during construction and afterward," one judge said. Others noted the substantial level of coordination and logistics the project demanded.

The latter point was also underscored by the project team members themselves. They said two factors made the stack of hurdles manageable, the first being the collaborative atmosphere of the design-build process, led by Hunt Construction Group as contractor and buttressed by design team members staying involved throughout. The other factor was the team's extensive use of three-dimensional modeling to coordinate major design, planning and logistics decisions.

"It was a true example of collaboration between Thornton, Hunt, AECOM [Ellerbe Becket], SHoP, Banker Steel and others," says Jonathan Mallie, principal at SHoP Architects, the facade design consultant. "We used the BIM model across all the parties to solve very complex issues in a short amount of time."

Such collaboration helped drill down to "the most cost-effective and the most sequence-effective" ways to address challenges, says Kenneth Johnson, executive vice president and Eastern division manager for Hunt.

The use of 3D modeling was also important for fabricating complicated connections of the facade, which came late in the design process, says Michael Squarzini, managing principal at structural engineer Thornton Tomasetti. "It let the steel fabricator hit the ground running and do mill orders right away, pulling it into the design team's time frame," he says.

Coordination helped the project move along from its March 2010 groundbreaking to a September 2012 opening. It also allowed for the smooth incorporation of features such as 100 luxury suites and two full concourse levels around the precast seating bowl, as well as background elements such as a pair of 80,000-lb elevators ferrying trucks to below-grade loading docks. Coordination was especially critical when the team installed the complex steel facade, despite the fabricator going bankrupt during the project.

Challenges early on included opposition from some community members, including residents of structures slated for demolition to make way for the project. The arena anchors a 22-acre, 16-building residential and commercial development site that has had extensive delays and has faced opposition. FCRC recently signed a proposal to form a joint venture with Shanghai-based Greenland Group to develop Atlantic Yards, excluding Barclays Center and B2, the first housing tower.

When legal challenges and property acquisition delays prevented access to the whole arena site, FCRC asked the team to work around it, Johnson says. "We worked the whole sequence of building around the property acquisition schedule," he says.

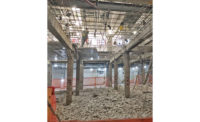

That meant the team would start sooner on foundation work, a significant element because much of the seating bowl is below grade to make the structure less imposing at street level. Still, staggered site access forced a more complicated roof erection sequence and delayed work on the busiest site housing the truck elevators, Johnson says.

That stage also required work around active city subway and Long Island Rail Road tunnels, including a 100-year-old tube the team had to expose and brace to build the foundation wall, Squarzini says.

Designing and erecting the roof posed problems because of its arched style and additional loads from the revamped facade, says Jeffrey Callow, Thornton Tomasetti vice president. "To ensure the arena could resist the arch thrusts, we used a tied arch system," he says. The roof spans more than 380 ft, supported by a pair of 350-ft tied arch trusses stretching across the arena's longer dimension.

The design called for the steel fabricator to make major portions of the roof in shippable sections, minimizing the need for welding, bolting and erection tasks on site, Squarzini says.

Such project innovations didn't make construction tasks less complex, however. For instance, the truck elevators and underground loading docks—forced by the tight, congested location—feature a 360-degree turntable that repositions trucks to exit facing forward. They required extensive load transfers in the superstructure, using large plate girders that spanned the dock. The elevators also meant crews didn't have the typical arena's loading dock access ramp during construction. Instead, the team built a ramp right through one side of the structure onto the event floor.

"It was the most constrained site we've ever worked on for an arena," Johnson says. "Access was a huge challenge, to get all of the men, machines, equipment—the large cranes to erect the roof—[inside] using the [temporary] ramp. We built the whole building, and then we took the ramp out with us. We had to finish steel erection with small cranes and other equipment from the bowl."

The close coordination paid off on the facade. The 12,000 weathered steel panels and 85-ft cantilevered entry plaza canopy were not part of the initial design and required extensive changes that 3D modeling made much smoother, Squarzini says. The team added 1,000 tons of steel to support the facade.

"The foundations had already been awarded," he says. "We had features that were locked in, but we were able to integrate the panels and not overstress the members in the structure. But the geometry was so complicated, the only way to hand it off was in 3D."

The exterior posed another challenge when the fabricator, ASI Ltd., went into default with only a quarter of its work done, Johnson says. Fortunately, the surety firm stepped in, and the team was able to proceed, losing only a few weeks from the schedule.

The main entry plaza—a highlight of the project—includes the distinctive canopy, connections to subways and a visual sight line to the scoreboard inside the arena.

"The view corridor between the transit station and the scoreboard creates a procession from the plaza to the lobby and into the seating bowl," Mallie says. "We looked at the canopy structure as the civic gesture of the project, the element of the building that reaches out to the plaza and creates that inviting entrance."

Barclays Center, Brooklyn

Key Players

Owner/Developer Forest City Ratner Cos.

Design Builder Hunt Construction Group Inc.

Architect of Record AECOM Ellerbe Becket

Facade Design SHoP Architects

Civil Engineer Langan Engineering & Environmental Services

Structural Engineer Thornton Tomasetti

MEP Engineer WSP Flack Kurtz

Steel Fabricator Banker Steel

Steel Erector James F. Stearns Co.