...construction is relatively seamless for the visitor, although an observer may notice the transition between the old and new slabs.”

Indeed, the Pacific War experience begins before visitors enter the museum, with the transition from the German-influenced historic Fredericksburg architecture to WWII, say David and Elizabeth Chu Richter of Richter Architects, Corpus Christi.

Visitors first encounter the bow of a submarine, which seems to be rising to the surface in front of the museum. General contractor Duecker Construction, Fredericksburg, used an actual American WWII submarine, the Pintado, sunk it 150 ft and formed concrete waves on the grounds around it, says Glenn Duecker, vice president and project manager.

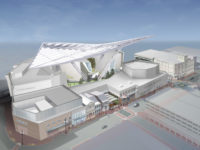

The museum’s military gray, galvanized-metal panel exterior begins to draw visitors into the military setting, and the three-story tower sets a nautical tone, says Chu Richter. The metal vaulted roof is reminiscent of Quonset huts, the dominant military construction in the Pacific during the period.

“Most architecture tells subliminal, hidden, sometimes unintentional stories,” David Richter says. “This architecture has a lot of embedded, intentional meaning, trying to support the story line.”

The contractor had to work in a tight space, while the museum was still operational, and maintain precise temperature and humidity requirements throughout the process to ensure protection of the historic collection, Duecker says. “It was a tough site, building from property line to property line on all four sides, amid lots of traffic and tourists,” he adds.

The contractor began construction in late 2007 by making a new entrance for the museum. “We built the new addition around the existing museum and across the front of it,” Duecker says. “Then we went in there and gutted the inside.”

The museum was closed from June to December while the contractor demolished the old gallery and rebuilt in that space.

“Probably the biggest part of the whole project was the HVAC system,” Duecker says. During construction, the contractor was required to maintain a temperature of 70 degrees, plus or minus two degrees, and 55% relative humidity, plus or minus 5%.

“There are units that do nothing but process outside air, units that inject humidity, units that remove humidity, and you can’t just move ducts around without coordinating,” says Duecker, who praised HVAC subcontractor Consolidated Service Co., San Antonio, for a job well done.

THC hired Cleary Zimmerman Engineers, San Antonio, to commission the HVAC systems to provide assurance that plans, installation and operation met requisite museum standards, Cavanaugh says.

Although Duecker’s electrician roughed in the wiring for the exhibit space, the real “magic” was performed by the Douglas Group, Houston, which designed the actual exhibits in the Bush Gallery, Duecker and Cavanaugh say.

Exhibit Concepts Inc., Vandalia, Ohio, had a separate contract for fabrication of the exhibition, and that company had two subcontractors—Bowen Technovation, Indianapolis, and Boston Productions Inc., Boston—who handled the audiovisual production.

“Those are the really neat gizmos and shows in this thing,” Cavanaugh says. “For example, they have five, 65-in. LCD screens designed into massive table tops that show five of the battle areas.” At key stages in the battles, significant people, maps and digitally enhanced actual Army and Navy raw film footage are highlighted on the screens.