San Diego State University football fans will celebrate a big day on Sept. 3, 2022, when the SDSU Aztecs take the field for the first time in their new stadium for a game against the Arizona Wildcats.

But for Clark Construction, opening day has represented a daunting milestone as crews have pushed to complete the $310-million project within two years. From the public vantage, the project will bring a new iconic sports facility to the city, but behind the scenes, its success hinged on extensive site preparation, executed concurrently with large-scale demolition and new construction—all under an aggressive schedule.

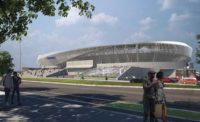

The 35,000-seat Snapdragon Stadium is set on 160 acres that was previously the site of Qualcomm Stadium, former home of the San Diego Chargers. The existing 70,000-seat stadium was located in the center of the site, surrounded by parking lots that nearly covered the rest of it.

For its redevelopment, SDSU had a bigger vision for what was possible. The new stadium would be set to one side of the site—with limited surface parking—while the opposite side would accommodate a future mixed-use development. The new development, dubbed Mission Valley, is expected to include up to 4,600 residential units, a 400-room hotel and an “innovation district” with 1.6 million sq ft of space to accommodate future research and laboratory tenants.

Crews built the most complex portion of the stadium first, then worked in a clockwise rotation to complete construction.

Photo by Aleksey Kondratyev, Clark Construction Group

From a procurement standpoint, SDSU needed to execute each component of the total site redevelopment separately, says Bob Schultz, associate vice president of real estate, planning and development at SDSU. However, both projects had to proceed concurrently.

“They are technically individual projects, but in reality, they are inseparable projects,” he adds.

At issue from the start was the fact that the original site was within a 100-year floodplain. Schultz says the university recognized that it needed to raise the entire site by up to 35 ft in some areas—not only to protect the new stadium but also to make the development more attractive to future tenants. Ultimately, the entire site would require more than 450,000 cu yd of imported fill to achieve the required elevation.

“We essentially became a dirt broker.”

—Albert Valdivia, Vice President, Clark Construction

For the stadium portion of the site, which Clark won a contract to build in February 2019, roughly 150,000 cu yd of infill would be needed. Albert Valdivia, vice president of Clark Construction, says the company also recognized the need to win the site development portion from a logistics standpoint as well as a business standpoint. “Once we had won the stadium project, we wanted to be able to treat it like one big job,” he says. “We knew we could be more efficient if we controlled the whole site.”

By the time the development went out for bid, Clark and its subcontractors already had a head start on how and where to find enough dirt near San Diego to meet the project’s needs. Valdivia says the team ultimately tested soils from nearly 50 project sites around the city that were planning to remove dirt, identifying 35 sites that could provide enough fill in time to meet the project schedule. Armed with solid sourcing and pricing, Clark was able to come in $20 million below the next closest bidder. “We essentially became a dirt broker,” he said. “That’s how we won the job.”

Adding to the challenge, the site itself also faced geotechnical issues that could present some settlement risks. As a result, crews would need to take the entire site down to 5 ft above the water table, with excavation depths ranging from 10 ft to 35 ft. From there, soils were refilled and recompacted to reduce possible settlement. At any one time, up to 30 scrapers were in use on site. Valdivia says that between the imported fill and the onsite soils that were recompacted, crews moved more than 2 million cu yd of dirt.

With much of earthwork underway in 2020—at the height of pandemic lockdowns—Valdivia says local traffic was light, so the team could keep a steady flow of material into the site. In total, roughly 40,000 truckloads of dirt were transported on site, averaging 115 trucks per day and reaching a daily peak of 400.

To help manage the dirt work, the team used drones in combination with Site Scan software. Drones flew daily, capturing thousands of site photos that were run through the software for analysis. The team overlaid images of existing daily conditions with finished CAD and topographic views, then calculated the amount of fill needed in different areas of the site. From there, data was connected to delivery schedules so the team could track production.

Between imported fill and recompaction of existing soils, crews moved more than 2 million cu yd of dirt.

Photo by Aleksey Kondratyev, Clark Construction Group

Demolition Options

In addition to the massive earthwork required, the team also had to determine how to demolish the existing Qualcomm Stadium. In its master plan, SDSU sited the new stadium adjacent to the existing one with the intent of leaving the stadium in place so the Aztecs could play the 2020 season there while work on the new stadium continued. When COVID hit and athletic schedules were placed in limbo, SDSU decided to move games to another location, where they would be played with no fans in attendance.

With the change in plans, options for demolition opened up. The original plan called for an implosion, which would leave the stadium up longer and enable the team to bring it down faster than conventional methods. However, an implosion would have to happen on a permitted date that could not be changed. An implosion also ran the risk of triggering air-quality fines and the need to clean up any dust that affected neighboring businesses. Plus, the implosion would take place directly next to construction of the new stadium, which would be well underway at the time of the scheduled February 2021 implosion date.

Clark shifted its plan from implosion to conventional demolition and saved two months of time.

Photo by Aleksey Kondratyev, Clark Construction Group

With more time in the schedule, Clark shifted its plan to conventional demolition, ultimately saving two months and shaving the budget. Valdivia notes that demolition of the above-ground stadium was only one portion of the job; crews also had to remove below-grade foundations, including nearly 1,500 steel H-piles. “Implosion would have gotten us down halfway, then it would have just been a pile of rubble,” he says. “[By using conventional demolition] we had it pretty much leveled in March, and we still couldn’t get all the foundations out until September. Implosion wouldn’t have helped because we still had to address below grade.”

With site soils properly compacted, crews put in foundations for the new stadium. With no underground spaces in the stadium, which was designed by Gensler, one side of the stadium sits on traditional footings and an elevated slab while the other uses slab on grade.

For the structure, a combination of cast-in-place concrete, precast concrete and steel was used. “We had to hustle with the concrete to get ready for steel,” Valdivia says. “Then, the steel had to get up quickly to get the rest of the concrete up. So there wasn’t a clean handoff. That was a challenge versus just having more of an all-steel or all-concrete structure.”

When completed, the Gensler design will deliver a stadium that emphasizes open air spaces.

Photo courtesy of Gensler

Crews started by first building the more complex portion of the stadium, which featured premium seating spaces. From there, they worked in a clockwise rotation to complete construction. Although the stadium is being delivered at a capacity of 35,000 spectators, it is designed to be expanded as needed, potentially accommodating up to 40,000 additional seats. As such, soils around the stadium were improved to accommodate future structural needs.

When completed, the Gensler design will deliver a stadium that emphasizes open air spaces. “We took inspiration from around San Diego, where people go on the weekends,” says Steve Chung, design director at Gensler Sports. “We drew inspiration from the beach communities and the craft food and beverage experience that is uniquely San Diego.”

At the corners, which are traditionally the cheaper seats in most stadiums, Gensler designed open decks that reference San Diego’s piers. The piers will provide standing room for 500 people with ready access to bars and concession spaces.

“Those piers will be an iconic aspect of the stadium,” Shultz says. “It’s part of the vibe of coastal San Diego.”