Access to water played a critical role in the development of Los Angeles into one of the country’s largest cities. In 1900, it covered 61 square miles and had 102,000 residents. The supply of water from the Los Angeles River—which ran dry in the summer months, and from wells drawing on local aquifers—was approaching its limit.

Frederick Eaton and William Mulholland were prime movers in securing a new source. Both were self-taught engineers. Eaton, superintendent of the Los Angeles City Water Company in the 1870s, first hired Mulholland as a ditch digger for water distribution canals. Eaton ran for mayor in 1898, on a platform calling for a new municipal water system, and after winning office got a bond issue passed that allowed the city to buy the private water company. Mulholland became superintendent of the Los Angeles Bureau of Water Works and Supply, now called the Los Angeles Dept. of Water and Power.

By 1901, Eaton, having served a two-year term, was a private citizen and turned his sights on the Owens Valley, 200 miles northward, on the eastern flank of the Sierra mountain range. In the early 1900s, the federal government was reclaiming land in the Owens Valley for a large irrigation system. Eaton began buying thousands of acres there from farmers who assumed he represented the federal Reclamation Service, which he did not.

Several lengthy articles about the aqueduct’s construction published in Engineering News were written by Burt A. Heinly, the private secretary of Mulholland, so they cannot be regarded as objective. In one 1913 article he states, “… the city’s Board of Water Commissioners ... secretly began in the early part of 1905 to take options on lands and appurtenant water rights. [By] July 1, 1905, these negotiations had reached a point where speculators could not impose upon the municipality, and the plans of the board with a report on the negotiations in the valley were made public.”

Construction kicked off in 1908. A cement plant in Monolith produced 1,200 barrels of portland cement per day. The workforce peaked at 3,900. Given the project’s remote location, the Southern Pacific railroad was contracted to build a 118-mile-long line from Monolith north to Olancha.

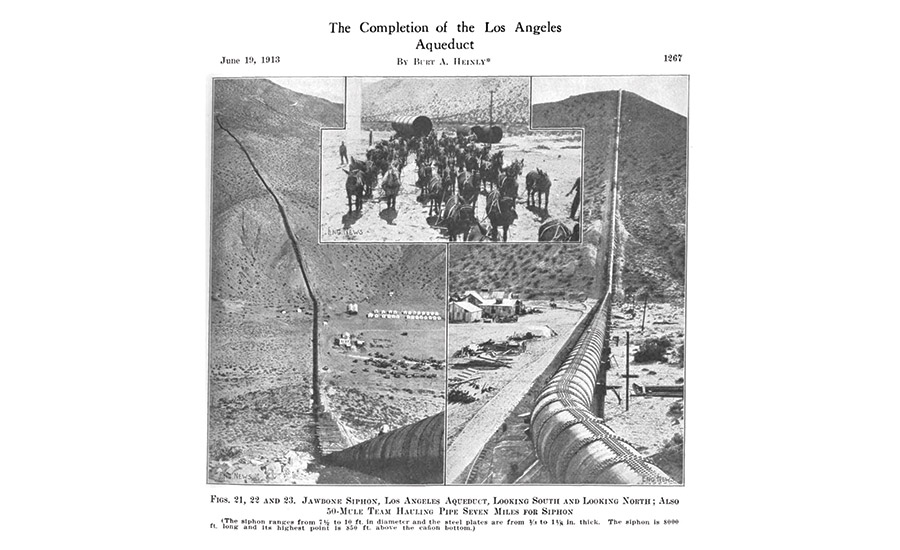

The aqueduct follows a 233-mile route southward, dropping from 3,812 ft elevation at its intake to its outlet at the edge of the San Fernando Valley, at 1,461 ft. The water is conveyed through 52 miles of tunnels, 60 miles of unlined and open lined canals, 98 miles of concrete-covered conduits, eight miles of reservoirs and 12 miles of siphons. Fifty mule teams hauled the large steel pipe sections.

The failure of a pressure-tunnel siphon in Sand Canyon 150 miles north of Los Angeles during a test phase was the project’s greatest challenge. The section of excavated rock tunnel that suffered the blowout was replaced with steel pipe, rush-ordered from a Pennsylvania mill. The repair work pushed back the completion by 90 days, to November 1913.

At two points where there were steep drops, the water drives turbines to produce 122 MW of electrical energy.

A city charter provision preventing the sale of the city’s water prodded many adjoining municipalities into being annexed to Los Angeles. By 1930, the city spread across 440 square miles and counted 1.2 million residents.

This political skullduggery was colorfully portrayed in the 1974 film Chinatown, starring Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway, with John Huston as a character based on a composite of Eaton and Mulholland.