French Fusion Reactor Advances, Amid Delays and Cost Revisions

A radial array of heavy rebar now marks the circular footprint of a vast experimental nuclear machine that is the centerpiece of a research program into atomic fusion, potentially a limitless energy source. Fusion research at the site will be challenging enough, but just getting the $16-billion facility up and running is no easy task.

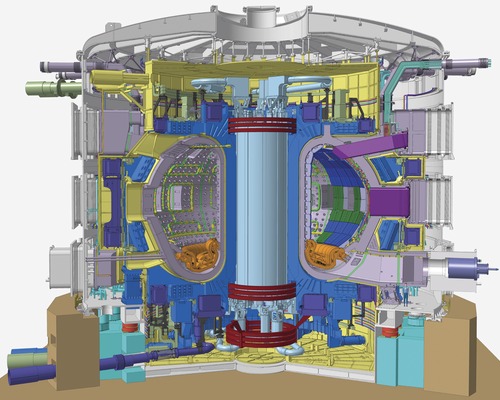

Weighing over three times more than the Eiffel Tower but far more complicated, the 23,000-tonne Tokamak reactor, located in southern France, is being designed in pieces all over the world; it will be assembled at the site near Saint Paul-lez-Durance, some 75 kilometers north of Marseille.

Like the Tower of Babel, the complex device has a lofty goal and many designers. The project is running years late and over budget. "A lot has been achieved, and, certainly, we will go ahead faster," says Sabina Griffith, spokeswoman for the ITER Organisation (IO), which is running the fusion project on behalf of the 35 participating countries.

With Europe funding around 45% of the fusion experiment, China, India, Russia, South Korea and the U.S. are chipping in less than 10% each. During some 20 years of operations, the project aims to generate 500 MW of energy from 50 MW of input heat, leading to a 2,000- to 4,000-MW demonstration plant.

Of the various routes to fusion, IO has chosen the Tokamak reactor system, which merges deuterium and tritium isotopes of hydrogen at temperatures around 150 million degrees Celsius. Arrays of powerful magnets will be needed to keep the superhot isotopes away from the doughnut-shaped reactor walls. IO's 30-meter-tall, 30-m-dia machine will be housed in a heavily reinforced, seven-floor concrete building, now taking shape.

"We need to design a large civil structure [that] can not only support the loads that are applied to it, but we [also] need to be able to put in large temporary openings," says Roger Holt, design manager for IO's buildings and infrastructure. Dense concentrations of rebar and the inclusion of tens of thousands of steel embedments add to the complexity, he says.

Holt is a principal engineer at W.S. Atkins plc., London, which leads the architect-engineer Engage consortium. Engage includes Empresarios Agrupados S.A., Madrid, and the Paris-based French firms Assystem S.A., and Egis S.A.

Engage likely will use up some of the 36-month extension allowed in its eight-year design-and-supervise contract, started in 2010, and its cost will be much more than the original $160 million, concedes another senior engineer.

Since work began some five years ago, the start date for fusion research has slipped by up to five years, to 2024, and the project cost has grown, says Griffith. To improve control and set new targets, the ITER Council in March replaced Osamu Motojima with Bernard Bigot as director-general.

Bigot will complete a cost and progress review that started last year, aiming to produce a new baseline this November. The aim is introduce "a more rational strategy of management," says Aris Apollonatos, spokesman at Fusion for Energy (F4E). This Barcelona, Spain-based group is managing the EU's contribution to IO, including site facilities.

To help explain the delays, Griffith says, "It's an R&D project [that] has scientists at the end of it." Scientists haven't appreciated "some of the engineering realities," agrees Steven Lisgo, one of about 25 physicists at IO. "We have started to understand how engineers work. … It's not many physicists who have to work to deadlines," he says.

Just as the culture clash between science and engineering is an obstacle, so is the procurement approach involving each of IO's seven members making their contributions in kind, officials concede. "Europe alone could have done it," but the aim was to spread the development effort, says Griffith.

Domestic agencies in each region procure parts of the machine to be shipped for assembly in France. The U.S., for example, is doing 75% of the steady-state electrical network. As part of that deal, ITER U.S. last January had an 87-tonne transformer delivered from South Korea to the Marseilles site.

Europe is delivering the 29 buildings and infrastructure at the 42-hectare site at a cost exceeding $1 billion. The buildings—totalling some 50,000 sq m—will consume 250,000 cu m of concrete, mostly in the Tokamak complex.

The complex is rising from a 1.5-m- thick, seismically isolated base slab in a 120-m-long, 80-m-wide, 17-m-deep pit. The 9,600-sq-m slab floats on 493 elastomeric bearings 18 centimeters deep atop 1.8-m-tall concrete plinths cast on a 1.5-m-thick foundation slab. A consortium led by Paris-based VINCI Group started work in 2010 and completed both slabs and plinths last August.

From the slab, VRF, another VINCI-led consortium, will build the Tokamak complex and other buildings in a $315-million contract awarded by F4E in late 2012.

VRF is working on the first level of walls, which include some of most heavily reinforced concrete in the Tokomak's support system, says Romaric Darbour, F4E's deputy head of site, buildings and power supplies. The team of designers and contractors have tested constructibility with 3D computer simulations and, in March, a full-scale trial concrete placement.

The machine will be founded on 18 spherical bearings distributed around a concrete ring. The ring will be connected to a concrete bioshield by 1-m-thick, 3.5-m-long, 3.6-m-tall radial walls. The Tokamak will be enclosed by a cylindrical, 30-m-dia bioshield that has, in places, walls more than 3 m thick.

Preparing for machine assembly, another team is putting up a 60-m-tall steelwork building next to the Tokamak pit. Six thousand tonnes of steel started to be erected last September, and the 900-tonne roof is due for raising this summer, says Darbour.

At present, IO is preparing to start procuring contracts this June to assemble the machine. By next spring, IO aims to appoint a construction manager to handle three contracts that cover the assembly and the electrical and mechanical installations, says Ken Blackler, head of assembly and operations.

At over $1 billion, the work has roughly doubled in price since 2010 because "the design was not ready," says Blackler. He believes assembly will start in 2017 and end around 2024. But he adds, "We are still working on the baseline."