Divers Searching for Way To Get TBM 'Bertha' Moving Again

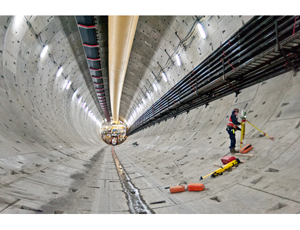

Joint-venture contractor Seattle Tunnel Partners needs divers to enter the chamber behind a tunnel-boring machine’s cutting head to investigate what possibly slowed—and subsequently forced a shutdown of—North America’s largest TBM, nicknamed "Bertha." The 57.5-ft-dia TBM is attempting to bore a 1.7-mile Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement under downtown Seattle.

On Friday, Dec. 6, Bertha, which had been boring at a rate of as much as 50 ft per day under a $2-billion contract in the larger $3.1-billion project, hit a snag at 1,019.5 ft bored, with its penetration and advancement rates dropping dramatically.

“We were applying the same force and only able to move a fraction of the distance compared to what we were able to do up until that point,” says Chris Dixon, project manager for Seattle Tunnel Partners. “Rather than continually mine at high pressure with a low advance rate, we thought it best to stop and assess the situation.”

The situation requires an “intervention.”

Matt Preedy, the Washington State Dept. of Transportation’s deputy project administrator, says the top of the machine sits 55 ft below grade, with Bertha stretching over 110 ft below the surface. At this point, operators aren’t sure if the obstruction is a clog within Bertha or something in her path.

Ballard Marine Construction, a subcontractor with experience in underground-pressurized situations, is now mobilizing and plans for crews to enter Bertha’s hyperbaric plenum behind the cutter head on or around Dec. 19.

In order to perform an atmospheric intervention, in which the pressure behind the cutter head is the same as the atmosphere, crews would need to drill through the fill above the TBM and construct a device to isolate pressure. Dixon says a hyperbaric dive, in which the divers would go through Bertha’s man-lock system to compress them into the proper pressure, would allow them to get inside the plenum much sooner.

Crews will clear the plenum of material debris about halfway, visibly freeing the upper half of the cutter head. “They will see the material in the chamber below them but not all the way to the bottom, and we’ll see what information becomes available at that point in time,” Dixon says.

The progressive investigation has divers first inspecting the cutter head, mixing arms, screw intake and debris-transporting conveyer belt to see if something has worked its way into the plenum, slowing the TBM's ability to extract excavated material. Crews may have to clear more debris for a better look. Further, by gaining an outside view of the cutter head, divers may be able to see if anything external is causing the slowdown.

Dixon says the project team hopes there is no damage to the machine or cutter head but won’t know until the divers do a visual inspection.

As Bertha progressed on its downgrade, it went through 30 to 40 ft of fill, mixed with a variety of contaminated soils and timber debris. Below 40 ft, crews expected—as per extensive geotechnical data obtained, pre-bore, by Shannon & Wilson—native soils, a complex glacial till mix of silts, sands, clays, gravel, cobbles and boulders. Data shows Bertha will encounter all sorts of mixes throughout the path as it moves, at points, all the way to 200 ft below surface level.

"We know we have a lot of ground variations, big thick layers of clay, big thick layers of sand and gravel and silts and always a potential for boulders or cobble,” Preedy says.

“We don’t know if we are in soils we were not anticipating until we get inside and see what we’ve encountered,” Dixon says. “We know we will encounter boulders along the way—the technical documents are pretty clear [on that].”

If a boulder proves to be the issue, Bertha’s rotating head is designed to break it up. If Bertha can crunch it down to pieces 3 ft dia or less, those pieces will fit in the plenum and move through the system. But boulders don’t always cooperate. Some boulders are so large that the cutter head has difficulty breaking them up; also, if the rock sits in loose soil, the boulder can potentially spin right along with the cutter head, making progress “problematic.”

In either of these situations, divers will move into the 18 in. of space between Bertha and the boulder and use hand tools to break up the boulder.

Bertha is now “roughly on schedule,” Dixon says. Even though labor issues, hardened grout and a conveyor screw clog has delayed boring, Bertha was making better-than-expected progress during what was planned as a “slow and deliberate” drive toward Safe Haven 3, at 1,500 ft—also where Ballard Diving was scheduled for a plenum inspection.

Plans were to push Bertha into “full production mode” after Safe Haven 3 in early 2014, moving her under the existing Alaskan Way Viaduct and under downtown Seattle. First, though, Bertha needs to get to her safe haven, and it will take the intervention of divers to move past this obstruction.

This story was updated Dec. 18, 2013, to identify correctly the specialty subcontractor working on the project. It is Ballard Marine Construction, not Ballard Divers.