| + click to enlarge |

EMAAR

|

William F. Baker, SOM’s structural partner for the job, does not underplay the amount of effort poured into the design of the 479,830-sq-m vertical cantilever to keep it as simple and repetitive as possible. “You wouldn’t believe the amount of time it took [just] to get the core right,” he says.

| + click to enlarge |

More than 200-m-tall steel spire sprouts from tower’s 585-m-tall concrete base.

|

But Baker is somewhat understated about the sophisticated design’s realization: “Construction is uneventful because the structure is not complicated.”

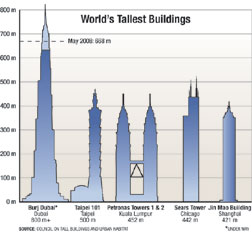

That is easy for Baker to say. He did not have to work out the nitty gritty of “extruding” the record-breaker on its way to superseding the 509-m-tall Taipei 101 by a whopping 300 m (if rumors of the final height are true). The difference is equivalent to a 70-story-plus tower—no mean feat in itself.

The engineer does not have to organize and lead the vertical wagon train of up to 8,000 workers—moving them up and down and providing for their daily needs for five years.

It was not on Baker’s shoulders to pump concrete 600 m up, keeping it fluid for the 30 minute ride to the top. (That is 152 m higher than the record set at Taipei 101, the tallest occupied high-rise.)

Baker did not have to maintain a vertical frame to extremely tight tolerances, nor did he have to jump the three tower cranes at extreme heights. He also does not have to operate the luffing-boom cranes, with cable as long as 805 m, or lift steel as high up as 740 m.

And the engineer did not have to cope with environmental plagues. In Dubai, summer temperatures can hit 130° F. In winter, high winds reduce crane and hoist efficiency to 50% because of safety shutdowns for days at a time.

Michael Goodman / ENR Dubai’s high winds and heat put demands on Burj Dubai’s building team.

|

On the 162-story Burj Dubai, the nuts and bolts of construction were largely left to Samsung Corp., the Seoul-based leader of the pack that is building the tower, and its army of subcontractors. The general contractor, which includes Belhasa Six Construct LLC, Brussels, and the local Arabtec Construction LLC, tells tales of traveling to unchartered territory to put the United Arab Emirates boomtown on the supertall-building map.

“As the building got taller and the tapered structure became more slender, working at extreme heights was very challenging,” says Ahmad Abdelrazaq, Samsung’s executive vice president for high-rise and structural engineering.

Taking concrete to such heights is only possible thanks to advances in materials technologies, structural-engineering theories, wind-and-seismic engineering, construction methods and computers, says Abdelrazaq. Still, “there are not many analysis programs available to do the construction sequence that includes the effects of creep and shrinkage [over] time at those heights, especially for concrete,” he says.

|

| ALABBAR |

To help keep the 585-m-tall structural-concrete portion vertical, Abdelrazaq prepared a “very detailed” construction sequence analysis and ran it monthly. He says most contractors do not do that.

Samsung also implemented the most extensive structural-behavior monitoring program in the history of building construction. The research, which measures load distribution throughout the frame as it is built, allows Samsung to correlate design with reality. “It gave us more confidence,” says Abdelrazaq. “To see actual data demonstrate what you dreamed about is very special,” he adds. The data will likely be shared with others, he says.

In the end, Samsung and its team produced a concrete superstructure very close to design assumptions, investigated in creep and shrinkage tests carried out three years ago, says Kyung-Jun Kim, Samsung’s project director.

| + click to enlarge |

|

Abdelrazaq attributes the positive outcome in part to the sequencing analyses. “It was more sophisticated than what was done during design,” he says.

He should know. From 1987 through 2004, Abdelrazaq, a structural engineer, was working at SOM’s Chicago office. His spent his last year designing the tower he now is helping to build.

Abdelrazaq’s former colleagues at SOM, which is providing architectural, interior, structural and mechanical-electrical-plumbing design, agree the job is height- and climate-challenged. “If it were easy, everyone would do it,” says Roger E. Frechette, SOM’s MEP...

kidmore, Owings & Merrill’s lead structural designer for the $1.1-billion Burj Dubai—already a 668-meter concrete- and-steel giant—is blasé about the complexity of construction, even at the upper reaches of the desert “cloudbuster.” But for most others on the unprecedented vertical expedition, the trek to the top—a rumored 800-plus meters—is as exciting as a trip to outer space.

Related Links:

Related Links: