Maturing Visualization Tools Make Ideas Look Real

|

| I-Room. Construction information workspace links programs in synchronized display. (Photo by Tom Sawyer for ENR) |

Making fast decisions is easy. Any fool can do that. Making good decisions fast is whats hard. Now, more and more firms are turning to visualization tools to help make that possible. A look at how some are doing it suggests that a revolution in construction communications is under way.

People up and down the chain of construction are churning out graphics created with blends of digital photographs and three-dimensional design data. They are manipulating images as models or animated construction sequences, or snapping off screen shots to be e-mailed or printed as instant renderings or graphical instructions to subs for display or distribution. And they are finding that the imagery is not only relatively inexpensive and easy to produce, but makes a superb tool for conveying complex information.

"It [3-D imagery] is a wonderful communications tool," says Paul Case, president of Urban Building Inc., Los Angeles, which offers development and project and construction management services, specializing in high-end commercial and institutional work. "It allows people to understand buildings better." Case has learned that getting people to understand better and more quickly can speed projects through the decisions that stand between ideas and work under way.

Selling Ideas

Lt. Cmdr. Jack Dempsey, a U.S. Coast Guard civil engineer pioneering facilities planning tools based on building information modeling, says the ability to use model data to generate even simple isometric drawings and renderings can propel design meetings directly past explanations to decision-making with surprising ease.  Click here to view images

Click here to view images

Last December, for instance, Dempsey was tasked with an almost impossibly fast-tracked, $625,000 project to renovate a facility on Yuerba Point Island in San Francisco Bay for a joint operations center. But he also had to deal with the ticklish problem of selling the plans to the two officers who were going share it as they combined their formerly independent commands.

Dempsey purposely presented what looked like a low-tech approach. He got architect Kimon G. Onuma, Onuma & Associates, Pasadena, Calif., to pull a few isometric line drawings from a highly detailed 3-D model of the project being created with ArchiCAD. When the meeting opened, Dempsey says he went straight to them. "When we got that one little picture up, it was all over," he says. "The ability to communicate the concept in quick, intuitive means really turned the tide."

Dempsey puts it simply: "If you are going to close the deal you are going to have to communicate a lot of information to someone who does not know how to read plans. Its the presentation of information. There is a lot under the hood... its not eye candy....But if they like it just for the picture, fine. Its good both ways."

With the plan approved, builders jumped to construction sooner and gained three weeks on the schedule. The combined Sector Operations Center, which is one of about 40 similar Coast Guard operation centers being created around the country, was to open July 7.

Coordinating Teams

At the other end of the spectrum of concept communication, model-generated graphics are helping construction professionals visualize, validate and explore complex sequences with each other before the job starts and the clock begins ticking.

|

| Imagine That. Virtual master plan shows how buildings fit before they are designed and built. (Image courtesy of Urban Buildings Inc.) |

"Virtual planning helps everyone understand at the speed of thought," said Greg Knutson, general superintendent with M. A. Mortenson Co.s Bellevue, Wash., office, during a presentation at the Center for Integrated Facilities Engineering at Stanford University in late June. Mortenson makes liberal use of construction model-generated graphics to explain requirements to subs and speed and coordinate work.

Knutson says 4-D model-generated graphicsthose that introduce time and scheduleare especially useful because they can be navigated like 3-D models, but also played like movies. "At a glance, in 30 seconds, you really understand the essence of the issue," he says. Processes can be paused, reversed, or sampled into stills that can be printed out, e-mailed or burned to CDs.

"The use of 3-D and 4-D really opens the door to innovation and process improvement," Knutson says. "It really promotes collaboration and problem solving."

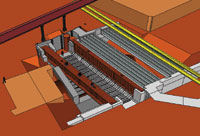

|  |

| High Stakes. SPSs crash project was tested virtually, first. (Photo and Image courtesy of Strategic Project Solutions) | |

Andre Koerckel, an implementation leader for Strategic Project Solutions, San Francisco, points out how critical such coordination and communication can be. As part of construction of a railway link between London and the Channel Tunnel last year, SPS was given a 51-hour window to shear the top off of a major sewer line and cross it with a rack of girders and beams and a steel deck fabricated in seven panels off site. It faced liquidated damages of $350,000 per hour, or $1.7 million per day, if the job ran long.

"Many [project team members] believed this process and volume of work in the time available was impossible," said Koerckel at CIFE. But after modeling it for...