Nearly a decade before the Brooklyn Bridge opened for business, tunnelers successfully bored 25,081 ft, or roughly five miles, through the Hoosac Mountain in western Massachusetts. For more than 40 years after opening in 1875, it was the longest tunnel in North America.

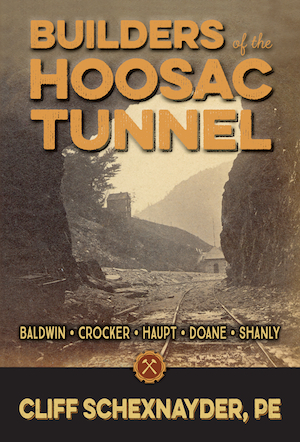

New tools and materials, the designs of which led to others still in use, were developed to complete the massive tunnel, according to construction scholar Cliff Schexnayder, who wrote the new book "Builders of the Hoosac Tunnel" (Peter E. Randall Publisher, 2015).

Although the project featured early prototypes for tunnel-boring machines, it was nitroglycerin and pneumatic rock drills that eventually helped engineers to complete the work, which took more than 20 years. During the project's early years, workers chipped away at the stubborn rock face by pounding hammers against steel drills, which special laborers, called shakers, would twist slightly between blows.

"The introduction of the Burleigh Rock Drill into the Hoosac Tunnel marked the beginning of modern tunneling," Schexnayder writes. "Mechanically powered rock drilling was no longer a dream or an inventor's tinkering—it was finally a practical reality."

The epic project did not come without its setbacks. For example, the book details a chilling scene in October 1867, when 13 men died inside a 581-ft-deep central shaft after naphtha lamps started a deadly blaze.

Other parts of the book detail fascinating stories of early American engineers whose audacity, innovation and persistence paved the way for future infrastructure.