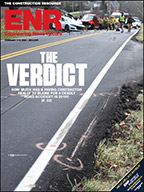

Opposing attorneys were summing up their cases on June 15 in the manslaughter trial of three construction managers and a now-defunct subcontractor for the 2007 Manhattan high-rise fire that killed two firefighters. Predictably, they sharply disagreed over who was to blame for those deaths and 34 other injuries.

Prosecutor Joel J. Seidemann told jurors that fault lies with the defendants, who were tasked with removing asbestos from the former Deutsche Bank building and deconstructing its 40 floors. That work on the structure, damaged in the 9/11 attack in 2001, was completed in January.

Throughout the 10-week trial, prosecutors argued that a cigarette sparked the fire that killed firefighters Robert Beddia 53, and Joseph Graffagnino, 33, and that site safety manager Jeffrey Melofchik, 49, a former executive of project contractor Bovis Lend Lease, so often shirked his duty to enforce a non-smoking policy on site that workers cut cigarette holes in their face masks.

Prosecutors also claimed that Mitchel Alvo, 58, a site manager for the sub, The John Galt Corp., and asbestos cleanup foreman Salvatore DePaola, 56, sliced a 42-ft section into a standpipe that could have sent water to quell the blaze. The defendants, including the Galt firm, are charged with several counts of criminally negligent homicide, manslaughter and reckless endangerment.

Defense attorneys, as expected, contend that their clients were “scapegoats” for the failures of government inspectors, larger companies and institutions and a “perfect storm” of other factors. Melofchik attorney Edward J.M. Little stressed the scapegoat point by relating a Biblical parable that gave rise to the term. “When something terrible happened, a tragedy hit, the villagers said somebody had to be blamed for this,” he said. “They literally blamed their troubles on a goat and drove it out of a village.”

Soft-spoken and understated, Little’s cool demeanor in addressing jurors mirrored the dispassionate way that he urged them to treat the case. “There are tragic accidents. There’s not always someone who’s negligent, and there’s not always somebody who’s a criminal," Little said. "This is a very emotional case. It can’t be decided on sadness, or anger, or vengeance. It has to be decided on evidence, on reason, and the rule of law.”

Little and other defense attorneys pointed to others who they believed shared responsibility for the tragedy, including officials of the city's fire department, its departments of labor and environmental protection, and the Lower Manhattan Development Corp., which owned the building after the attack.

The defendants' experience and responsibilities were consistently downplayed during testimony, prompting an animated and indignant prosecutor to accuse them of being disingenuous. Seidemann, who said that the three managers had a combined total of about 60 years of jobsite experience, noted their claim that they could not identify the building standpipe that held its water supply.

“One thing that’s amazing about these defendants: they touted their experience before the fire,” said Seidemann, an assistant district attorney in Manhattan. “They knew nothing after.” He noted that several prosecution witnesses were able to identify the pipe and its function. “Who’s playing dumb?” he said. "How is it the workers know it’s a standpipe, and the inspectors don’t?” Seidemann added that a "mosaic" of other negligent acts painted a picture of "overwhelming guilt."

While Little contended that Melofchik dutifully performed daily inspections on a 158-point checklist, Seidemann countered that the site manager simply “punched a computer button” to mark lists reflecting what his superiors wanted to see. “These were daily lies,” Seidemann said. “The only thing that changed was the date.” He added that the defendants rushed their jobs because financial pressure at the jobsite “trickled down and weighed down” on them.