Team Building 1,397-ft 432 Park Avenue Tower Went to Extremes to Make It White

For the exposed perimeter tube, crews eventually achieved a four-day typical-floor cycle until floor 45; above that, a floor took three days. Outrigger floors took five to eight days, as anticipated.

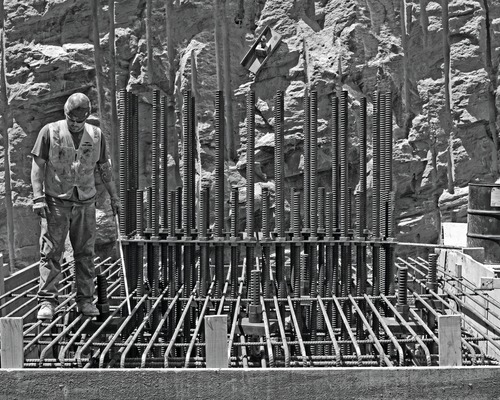

To keep pace on the perimeter tube, rebar maker Retech Systems LLC prefabricated the 97-ksi rebar, supplied by SAS Stressteel Inc., into 15.5-ft-tall column modules, following a system patented by consulting engineer Felix E. Ferrer. A template holds the bars in position. Roger fabricated spandrel rebar into cages. For the first 20 floors, crews site-assembled a 93.5-ft-long spandrel cage—a full building side— leaving out stirrups at column locations.

The first cage "took 15 minutes from the time it was picked to the time we disconnected the crane hook," says Rodrigues.

At level 20, the crane picked, per side, two spandrel cages, which were prefabricated at Roger's yard in Brooklyn because there was no longer room available on-site. "If we had to pick the longer cage at the top of the house, it would have been a disaster because of the high winds," says Rodrigues.

To reduce congestion that could lead to honeycombing and voids, spandrel rebar was 80 ksi, instead of a lower strength. Overlapping corner cages were the most complicated to install, says Rodrigues.

Roger crews first set the column rebar cages. Workers then installed self-climbing column-and-beam custom steel formwork with stainless-steel face sheets and built-in chamfers, reveals and drip notches. "We fabricated the forms to the exact shape of the columns and spandrel beams," says Michael Schermerhorn, senior account manager for Doka USA Ltd.

Next, crews set the slab forms and closed column forms; slab rebar and spandrel rebar cages followed. When the spandrel rebar cages were set into the form, long bars for the columns stuck up through the spandrel cage. Crews then placed concrete in the columns. The next day, they placed slab concrete and spandrel concrete. A day later, crews would set the column cages on the floor above and open and unfold the column and spandrel forms. Then, workers rolled the forms outbound, 2.5 ft onto the top level of a four-tiered work platform. Once preliminary work was completed, the form climbed to the next level.

Pumps were on the street, riser pipes ran up the core wall, and the placement boom was set on a gantry on the core. The boom had to reach to the perimeter, more than 30 ft below.

Though the concrete was self-consolidating, "we vibrated the heck out of it to make sure there were no voids," says Roger's Rodrigues.

Pumping white concrete uphill was a big challenge. Crane buckets were at the ready in case of pump clogs, especially for spandrels, which were cast a complete level at a time to avoid cold joints.

The team leaders closely monitored the concrete and adjusted the mix when necessary, especially for the 10,000-psi concrete in the building's upper reaches.

Casting started in the winter. "With every pour, we wanted to change to gray concrete, which enjoys cooler weather," says Chuck LeRoux, LL's senior project manager. "When it got warmer, the operation got better," he adds. Still, the "white mix is less forgiving than gray" and was always "looking for a hug," he says.