In New Aviation Bill, Congress Mulls Hikes for Construction, Security

As airlines and airports struggle with persistently low passenger volumes, Congress is moving on legislation that is likely to give a boost, though a small one, to federal airport grants for the next several years. The legislation is still a long way from passage, but when it's final it is likely to include added aid for airport security projects and mechanisms to push big runway projects more quickly through their environmental reviews.

At issue is what will succeed AIR-21the Wendell H. Ford Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the 21st Century. The 2000 statute, named for the former longtime senator from Kentucky, provided a huge jump in aid for the Federal Aviation Administration. What made design and construction firms smile was AIR-21's record hike in the Airport Improvement Program, which funds construction grants. The law drove AIP up 64%, to $3.2 billion, in 2001, and then boosted it further, to $3.4 billion in 2003.

|

| FY2002; Source: DOT Inspector General, from FAA Data |

With growing federal deficits pinching nondefense budget accounts, lawmakers realize another AIR-21-like leap in AIP won't fly this time around. Still, Congress won't settle for freezing program funds in the new bill.

AIP grants are only one revenue source for airport construction. The bond market is the largest. With the decline in air traffic, airport construction bond volume slipped 19% in 2002, but still totaled $10 billion, according to Thomson Financial. A second source is passenger facility charges of up to $4.50 per flight segment. Last year PFC collections totaled $1.86 billion, FAA says.

But AIP is "more important now than it's ever been in the past," contends Jerry FitzGerald, president of PB Aviation, New York City. He says airports are straining to pay for federally mandated security upgrades, "which really has a serious impact on the financial capacity of airports to fund infrastructure improvements."

|

"Many of the airports that we rate...have essentially deferred much of their capital spending," says Kurt Forsgren, head of Standard & Poor's transportation public financing group. (S&P and ENR are units of The McGraw-Hill Cos.) Airlines' financial woes have particularly affected terminal projects. "The airlines have been doing anything they can to either keep level or reduce the rates and charges they're paying to airports," says Barry L. Molar, manager of the FAA's airports financial assistance division. Economic factors haven't affected only terminals. They also were behind Minneapolis-St.Paul International's decision to delay a $500-million, 8,000-ft-long runway until October 2005.

AIP can be important for large airports. For instance, at Denver International, AIP provides 72% of the $170-million cost for its new 16,000-ft runway. It's scheduled to open Sept. 4. "This is the most important capacity project we currently have on our list," says Woods Allee, Denver's budget administrator for maintenance and engineering

For small airfields, the grant program is critical. It accounts for more than 60% of small airports' revenue, compared with less than 10% for large and medium hubs, according to the General Accounting Office. "Many of those small airports are operating near break-even or in a deficit, and they really rely on AIP to meet capital needs," FAA's Molar says.

There are three main proposals for new legislation, from the Dept. of Transportation, the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee and another expected soon from the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.

For construction, the main item is how much AIP will get. DOT's proposal, announced March 25, would hold the program at $3.4 billion for four years. That's only about $20 million above 2003's appropriation. "This funding level will support the major airport capacity projects that provide the greatest benefits to the [National Airspace System] as well as assistance to medium and small airports," Transportation Secretary Norman Y. Mineta told Congress.

Key members of Congress and industry officials think DOT's plan falls short. On May 1, the Senate commerce panel approved its alternative. It has $3.4 billion for AIP in 2004, then raises that to $3.5 billion in 2005 and $3.6 billion in 2006. The House committee had not introduced its aviation bill by ENR press time, although the aviation subcommittee tentatively was to vote on a measure on May 14. A committee spokesman declines to say what the House bill will contain, but panel leaders have called for AIP increases of at least $100 million a year.

Another key element in construction's eyes is retaining AIR-21's provisions aimed at ensuring that Airport and Airway Trust Fund dollars are spent on airport projects. That budgetary protection is just as important as the AIP funding level, says James A. Wilding, who retired May 2 as president of the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. AIR-21's safeguards are congressional "points of order."

Mineta says the Bush administration typically doesn't take positions on points of order. But he reiterated "strong support" of the concept behind the safeguards. The Senate committee's bill retains those budget protections. The House panel is expected to do the same.

Airports also want additional money in the bill to pay for security requirements Congress mandated in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. In particular, they're focusing on costs to install explosive-detection machines to screen passengers' luggage. The American Association of Airport Executives and Airports Council International-North America estimates those expenses at $3 billion to $5 billion, says Brad Van Dam, the group's staff vice president for legislative affairs.

Since 9/11, Congress has given airports about $1 billion for airports, including $235 million in the war supplemental bill enacted on April 16, Van Dam says. The Transportation Security Administration is negotiating five-year funding agreements for security projects with about 20 U.S. airports, says Administrator James Loy. TSA spokesman Brian Turmail says commitments would be about $1 billion for the 20 airports.

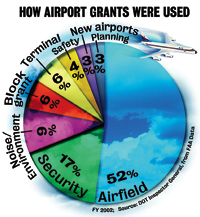

Airports also have turned to AIP for help with security. Last year, with AIP eligibility broadened by Congress to cover more types of security projects, security grants from the program jumped to $561 million, from $56 million in 2001. Security measures shouldn't be funded from money that's meant for infrastructure, says Lee Powell, president of APAC-Georgia's Ballenger Paving Division, Greenville, S.C. "That's like cutting one's nose off to spite one's face," he says. Adds PB Aviation's FitzGerald: "Although everyone has to agree security is an essential part of transportation, as soon as you say that, you should speak to a separate security fund."

The Senate commerce bill would do just that, establishing an aviation security capital fund of $500 million a year. Its revenue would come from already authorized security fees and would be separate from the Airport and Airway Trust Fund, which finances AIP. Commerce committee Chairman John McCain (R-Ariz.) says his panel's bill "really authorizes significant increases. It also stops the flow of AIP money from airport improvement into security." Airport lobbyist Van Dam agrees: "I think what the Senate [committee] did was great news."

The House transportation panel supports financing security from sources other than the aviation trust fund. DOT's proposal doesn't have a separate security fund, but the agency supports the idea. "It is certainly the intention of the administration to ensure that we don't jeopardize very much-needed aviation infrastructure projects at the expense of security-related enhancements," a DOT spokesman says. "That's a clear intention of the Secretary."

DOT and Congress also favor expediting planning and environmental reviews for projects that add aviation capacity. "We all worry about the environment but you can do more damage to the environment by waiting 10 years for a new runway with planes waiting on the ground," says William Fife, director of aviation for DMJM+Harris in New York. Runways seem to face particular delays, says Brian Deery, senior director of the Associated General Contractors' highway and transportation division. "They make highway projects look like a dream," he says.

There have been attempts to speed up the process, including President's Bush's executive order last September. "There's been some effort," says Yale Lyman, business development manager for Watsonville, Calif.-based Granite Construction Inc.'s heavy construction division. "But results have been dismal." Michael D. Steer, URS Corp.'s air transportation director in Hunt Valley, Md., says, "Our experience in the environmental field [is] the longer the planning takes, the more susceptible it is to technical and political change."

Mineta says DOT's plan would let FAA designate priority projects and "direct other federal agencies to give substantial deference" to DOT's statement of the need for the projects. The Senate committee calls for finishing runway project planning and environmental reviews generally within five years after the airport submits a capacity plan. It also includes concurrent environmental reviews, "where appropriate." "What's being suggested should help and make things go much more smoothly," says Nigel Finney, director for planning and environment for the Minneapolis-St. Paul area's Metropolitan Airports Commission.

|

| KEY SOURCE AIP Aid Funds 72% Of New Denver Runway's $170-Million Tab. (Photo Courtesy Of Denver International Airport) |

There are skeptics. "The environmental community is generally skeptical about streamlining proposals in transportation," says Deron Lovaas, deputy director of the Natural Resources Defense Council's smart growth and transportation program. "You're not going to deal with all the potential causes of [project] delay by imposing one-size-fits-all deadlines and mandates about who's in charge under the environmental review process."

Air-21 expires Sept. 30 and some observers are optimistic that Congress will act by then. "The pieces are set up on the board in such a way that they've got a good chance," says David Bauer, the American Road & Transportation Builders Association's vice president for government relations.

But there's a new stumbling block in the Senate. The commerce committee added a provision that allows more long-distance flights at Washington Reagan National Airport. Virginia's senators, whose constituents oppose expanded flights, will try to delay the bill if that provision remains. "It's a problem," McCain acknowledges. "We need to work it out."

| COMPETING PLANS FOR NEW AVIATION BILL | |||

| DOT | SENATE | HOUSE | |

| Status: | Released March 25 | Commerce committee approved May 1 | Not yet introduced at press time; subcommittee vote tentatively scheduled for May 14 |

| Length: | Four years | Three years | Not known, but multiyear expected |

| AIP funding: | $3.4 billion a year | $3.4 billion in 2004, $3.5 billion in 2005, $3.6 billion in 2006 | Not known, but transportation committee leaders have recommended at least $3.5 billion in 2004 and $100-million annual hikes after that |

| Airport security funding: | Would be drawn from AIP, but DOT supports separate funding | Sets up new $500-million annual fund for airport security projects. Financed through already authorized $2.50 fee. Expected to be administered by Dept. of Homeland Security | Committee leaders back non-AIP funding source |

| Project "streamlining": | Included | Included | Expected to be included |

| Sources: U.S. DOT, Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee, House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee. | |||