...total of 50 welders,” says Davis. Normally, there are 25.

To keep steel 12 to 14 floors ahead of concrete deck work and allow welding to be completed between steel and concrete operations, DCM had to have the building inspected for stability.

FLACK + KURTZ

|

FLACK + KURTZ

|

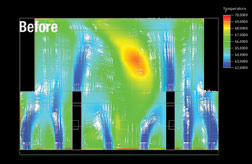

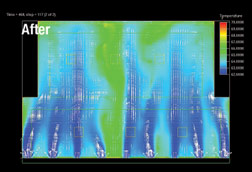

FLACK + KURTZ Studies let engineer stop heat buildup under raised floors (above, middle) and see temperature stratification in offices (top).

|

Extensive welding was a consequence of the expressed structure and Interstate’s decision to weld many interior core braces, says the engineer. It also is attributable to the high level of tension in core columns due to wind, seismic, hardening and disproportionate collapse criteria.

The intumescent paint also was a bother. The area had to be cocooned to keep the temperature acceptable and the elements from washing paint away. Quality control, for smooth application for looks and required thickness for the fire rating, was tricky. Early work had to be redone. “The first three months of the nine-month job were the learning curve,” says FCR’s Sanna.

Perhaps the happiest subcontractor is the curtain wall supplier. “It turned out to be a great project, even with all the engineering challenges,” says Lou Niles, president and CEO of Benson Industries LLC, Portland, Ore.

The sun screen blocks half the heat gain, allowing the building to meet the New York state energy code and still use ultra-transparent glass. The irony, agree sources, is that the ceramic rods bounce sunlight into the building at certain times of day, increasing glare. Consequently, window shades are needed. The sunscreen solved one problem and created another, says Daniel H. Nall, F+K’s director of advanced technologies.

The shop-assembled, pressure-equalized, thermally broken unitized curtain wall consists of 9,600 units. Most have an adapter to support the ceramic rods some 20 in. outside the window glass.

Benson Industries Rod spacing became a tug of war between architect and engineer.

|

Nearly 1,150 units are different. There are 170,000 rods, typically 4 ft 10 in. wide. The 5-ft-wide, story-tall units come in four types: a glass unit with an armature and ceramic rods; a ceramic-fritted glass-only unit for the notches; a glass-only unit for the exposed beam that penetrates the curtain wall and a sun-screen-only unit. Rod spacing varies, but is typically 3 to 4 in. except in the rod-free zones at eye level and other places.

For the rods, the architect switched from terra cotta to a stronger alumina silicate composite ceramic. The material is able to take the weight of a person. Still, broken rods dot the curtain wall.

Each rod is actually a sleeve over an aluminum reinforcing spline. Around the ends of each spline is an injection-molded silicone washer that isolates the rod from the spline, preventing rattling and serving as a buffer. The rods’ outside diameter is 15⁄8 in.

Aluminum combs, water-cut from extrusions using computer numerically controlled equipment, support the rods. Combs are connected to the glass unit through aluminum armatures at the unit’s ends. All outdoor fasteners are custom-made from high-grade stainless steel with a sandblasted matte finish, because “Renzo didn’t want them to be highly reflective,” says Jeremy W. Mucha, Benson’s vice president of engineering. Each unit has about 500 fasteners, when 50 to 60 is the norm.

Benson Industries Cladding unit, with rods, has 20-in. depth.

|

Every 30 ft, the screens have a concealed track for maintenance equipment. For window cleaning, crews are going to reach between the rods, says Mucha. Each unit has two, painted aluminum, diagonal sag rods, one at each end. They allow the assembly to move with the floor-to-floor live load deflection and the window washing swing stage lateral load.

The rods also needed to survive manufacture and service. They couldn’t provide perches for birds, either.

Then there were concerns about ice loads. Rods are designed to accommodate 1.6 in. of ice buildup. “That’s almost a solid sheet of ice,” says Mucha.

Benson Industries

|

Benson Industries

|

At the notched corners, the curtain wall installation was made more difficult because the units had to be dropped into the cavity in front of the slab and behind the exposed steel. In addition, there are 840 violations of the envelope. Each has potential for air and water infiltration, and thermal transfer. At the beam penetrations, crews first installed a silicone boot. Units went in next, minus the head rail, spandrel glass and back pan. They went in last.

Flack + Kurtz spent much time with Piano testing the limits of the ceramic rod spacing. Piano wanted big spaces to achieve his vision of transparency; F+K wanted closely spaced rods to limit heat gain. In the end, F+K specified one 30,000-cfm-capacity, factory-built air handling unit per floor. Two units would eat up leasable space and a larger unit would have had to be field-assembled, according to union rules. That was too costly.

The exoskeleton also complicated F+K’s work. During cold weather, beam penetrations become a ther-mal bridge, potentially causing condensation. To minimize the effect in very cold weather, the engineer developed a control protocol to stop humidifying the space for a few hours.

AMEC/George Mow Workers slid glass units between the slab and exoskeleton. Beam penetrations had special details (top).

|

F+K also engineered a 1.4-Mw cogeneration facility that serves the Times’ mission-critical power requirements, instead of a standby powerplant. The cogen plant generates 250 tons of cooling from waste heat.

“Intelligent” building controls in the Times’ space allow the building to respond to a utility emergency by allowing predetermined compromises of thermal and visual comfort to reduce electrical demand by 25%, says Nall.

The Times is the first multitenant building in New York City to have underfloor air displacement ventilation. UAD spreads fewer germs among occupants.

Though the building is designed to be 10 to 13% more energy efficient than the norm, it will have no LEED rating. The Times’ rationale is that certification would have distracted the team from creating a better work environment.

With the Times move-in about to begin and building completion set for the fall, AMEC’s Muldoon is looking ahead. Without revealing any post-Times job offers, he says that in the future he would shy away from a competitive GMP process. “If you force a CM into that tight a contract, there is more tension between the CM and the owner,” he says. “In the end, a negotiated GMP is better for everyone.”