Courses Are Expanding to Meet Gradually Growing Goals

Twenty-four states now have mandatory continuing education requirements for professional engineers. Proponents say these regulations provide an incentive for practitioners to stay on top of technology and offer the opportunity to develop skills. But critics worry about the quality and relevance of course material. "If you start looking at the content of some commercial programs, they dont seem beneficial to the profession," says one engineer.

Twenty-four states now have mandatory continuing education requirements for professional engineers. Proponents say these regulations provide an incentive for practitioners to stay on top of technology and offer the opportunity to develop skills. But critics worry about the quality and relevance of course material. "If you start looking at the content of some commercial programs, they dont seem beneficial to the profession," says one engineer. Observers say the growth in the number of states with continuing education requirements has slowed from a peak in the middle of the last decade. However, implementation of these requirements is still "clearly a trend," says Arthur Schwartz, deputy executive director of the National Society of Professional Engineers, Alexandria, Va. "Growth over the last few years has been incremental," he says.

Iowa was the first state to require continuing education for professional engineers in the 1970s. It remained the only state until Alabama joined it in the early 1990s.

Many others are ramping up. Missouris engineers began accumulating credits this year and New Yorks law will go into effect Jan. 1. At the same time, Maines voluntary program will become mandatory and North Dakota lawmakers have passed enabling legislation for its program. Rules now are being promulgated. Engineers in North Dakota will likely start accumulating credits as of Jan. 1, 2005.

|

Regulations in most states generally adhere to model guidelines for continuing professional competency drafted by the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying, Clemson, S.C. "The goal is to promote consistency among the various states," says Jerry Carter, NCEES associate executive director. These model guidelines require that engineers accumulate 15 professional development hours each year. One PDH is defined as one contact hour of instruction or presentation.

The guidelines give engineers considerable flexibility in satisfying this requirement. Typical acceptable activities include courses, seminars, in-house programs or training with engineering content; software instruction; and management or ethics courses. This flexibility in delivery method and content is intended to give engineers freedom to select courses that "will maintain, improve or expand the skills and knowledge relevant to the licensees field of practice," according to the guidelines.

"Because engineering is so broad, the licensee is given flexibility to chose courses," says Josephine Emerick, chairman of the professional engineering division of Missouris licensing board and senior project manager in the St. Louis office of URS. "It is up to the individual to chose relevant courses," she says.

Record-keeping is the responsibility of the licensee, and many engineers registered in multiple states say that keeping track of the PDHs is not too cumbersome. Matthew Stuart, senior structural engineer at Schoor DePalma, Manlapan, N.J., is licensed in 22 states that require continuing education. "State are flexible enough with the reporting format so that I only have to fill out one form," he says.

| Activities Considered Continuing Education |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

in-house courses, workshops, or professional or technical presentations made at meetings, conventions or conferences. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Source: National council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying |

Many engineers say that they participate in many more hours of qualifying activities than state regulations require. And sources seem to agree that the regulations primarily impact engineers who were not participating in continuing education. "Most engineers were already keeping up, but the law benefits those that were not doing continuing education previously," says James McCarter, chairman of the South Carolina Board of Professional Engineers & Land Surveyors and executive vice president at H2L Consulting Engineers, Greenville.

But sources critical of required continuing education say it does little to protect the public or enhance professionals skills. "The only people that benefit are providers," says Ronald Starling, chair of Arizona State Board of Technical Registration and principal of structural engineering firm Starling Associates, Tempe.

Engineering societies, universities and building product vendors have long been involved in providing continuing education to construction industry professionals. To varying degrees, these providers have seen greater demand for courses as more states have adopted requirements. "There is no question that the increased number of states [with mandatory continuing education] is a factor in increased demand," says John Casazza, director of continuing education at the American Society of Civil Engineers, Reston, Va.

ASCE provides continuing education material in technical and management topics in various formats, including live seminars, video courses and interactive Web seminars. It has seen participation in the courses more than quintuple since the mid-1990s, says Casazza.

Other providers have seen more modest growth. Since implementation of Minnesotas requirements in the late 1990s, participation in the University of Minnesotas programs has grown about 10%, says Lori Graven, program director for continuing professional education. The Minneapolis-based university sponsors conferences and seminars on civil engineering topics throughout the state. "A significant portion of the profession was already participating," Graven says.

In the last few years, commercial providers also have entered the continuing education market. RedVector.com Inc., Tampa, Fla., is one of several providers that delivers content on line. Founded four years ago with three employees, the company began by offering courses to engineers and contractors. It now has 52 employees and a library of 2,000 courses for eight professions in design and construction.

RedVector.coms courses range from $23 to $60 per PDH and are an inexpensive alternative to live seminars, which can cost hundreds of dollars when travel expenses are included, says Brent Craven, president. Online course delivery is well-suited to professionals in rural areas without many live continuing education options, and those working on projects abroad but licensed in the U.S., he says.

Most providers say that state requirements are not the only factor driving growing demand for continuing education courses. ASCEs Casazza cites increasing specialization and rapid advances in technology as being a big factor behind the desire for more training.

Providers also say that continuing education can help engineers career development. The courses can help "meet registration requirements as well as internal requirements for advancement," says Dave Raymond, president of the American Council of Engineering Companies, Washington, D.C. The council offers business and management courses tailored for engineers. "Engineers want to take courses to enhance their knowledge base," says Raymond.

For firms with in-house education programs, the main objective usually is the distribution of the organizations expertise to its employees rather than fulfillment of state requirements. "The primary issue is knowledge sharing, continuing education requirements are secondary," says Tampa, Fla.-based Mark Brewer, director of PBS&J University.

|

| SHARING THE KNOWLEDGE Employees visit wastewater treatment plant as part of MWH program. (Photo courtesy of MWH) |

At Broomfield, Colo.-based MWH, employees can participate in seminars on management, leadership and technical topics held at its various locations around the globe. The material from these courses also is available to employees through the corporate network. Helping employees satisfy state continuing professional competency requirements is just a small part of this larger effort. "Part of our commitment to our employees is helping them keep their licenses up-to-date," says Betsy Smith Redfern, chief learning of-ficer.

With growth in course offerings and providers, some sources worry about the quality of continuing education materials. "There is a lot of commercialism as a result of the requirements," says George Tamaro, a partner at Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers, New York City.

In order to control quality, a few states, including North Carolina, Arkansas and Florida, have adopted an approval process for providers. But Florida is the only state that requires licensees to take courses from an approved sponsor. Engineers licensed in Arkansas or North Carolina can take courses from other providers, but those are more closely examined during audits.

None of the states approve material on a course-by-course basis. In Arkansas, a prospective provider submits an application to the board with a course sample. "We dont have staff to approve each course offering," says J.T. Clements Jr., executive director of the State Board of Registration for Professional Engineers and Land Surveyors. "To accomplish the true objective of continuing professional competency, there would have to be review at that level," he says.

North Carolinas continuing education requirements have been in place for almost a decade and the board is considering changes, says Andrew Ritter, executive director of the Board of Examiners for Engineers & Surveyors. In particular, the board is examining its sponsor approval process, which is similar to that in Arkansas. "We are looking at tightening down the system," Ritter says.

|

| EYES ON ROAD Students observe demonstration in University of Wisconsin-Madison continuing ed course. (Photo courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison) |

But some providers caution that a complicated approval process could have a negative impact on continuing education. "If the approval process is elaborate, it will reduce the number of providers and the number of courses available," says Phil OLeary, chairman of engineering professional development at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

North Carolinas Ritter says the quality of most classes is high. However, he worries about the few that are deficient. "Although 99 out of 100 classes are probably great, a bad course damages continuing professional competency more than anything."

| Groups Continuing Ed Course Is Tough Love for Engineers Catherine Ellis, a San Jose, Calif.-based project manager at Kleinfelder Inc. with a masters degree in civil engineering, was warned to "take a stiff drink" before opening the letter containing the review of her training class proposal. Sri Dinakaran, a project manager in Dallas for engineer CTL Thompson, was pleasantly surprised when his submittal came back "only 70% hacked up." Both engineers not only lived through the dreaded Fundamentals of Professional Practice (FOPP) continuing education course offered by ASFE, a Silver Spring, Md.-based geotechnical engineers group, but they strongly extoll its practical benefits to working engineers and their employers. The once-a-year management and communication course, split into a proposal phase and subsequent in-class review and lecture, is a months-long undertaking that requires participants to meet strict deadlines and develop a thick skin. In addition to required readings and exams, students must propose and execute a research project on a topic that will directly benefit their firms management or bottom line. Project results are then presented in front of instructors and peers for tough critique.

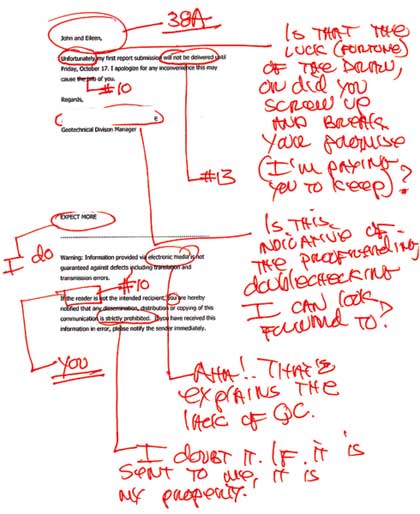

FOPP allows young engineers to make real-world mistakes early on. "Often, a project is not intriguing or you dont like the client. This is the time when professionalism is most important," says John P. Bachner, ASFE executive vice president and FOPPs guru. The course handles no more than 75 students a year and costs each more than $3,100, not including travel and time not in the office. Employers usually pick up the tab and are selective in who attends. "We send the up and comers," says Gerry Salontai, Kleinfelder CEO. "If someone couldnt make it through, it would tell us something." Bachner says more than 825 engineers have enrolled in FOPP since 1987. Graduates gain continuing education credit, but not all states recognize nontechnical training, he says. Surviving Bachners drill sergeant-like course management is a key hurdle. He is relentless with critiques of all written submittals, down to grammar in cover letters and e-mails. "I mark things up with a red pen until the paper bleeds," says Bachner (see sample, below). Face-to-face reviews are no easier. "There are people still angry at me after 15 years," he says. But, adds Ellis, "if you cant spell a word correctly, how do you expect people to trust your engineering?" Surviving graduates say the FOPP experience was "humbling" but has its benefits. Dinakarans project on CTLs contract terms has made him a firm expert on the subject. "Its helped me think a lot more," he says.

|