| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Strikes. Overwash to Dauphin Island from Hurricane Ivan (center) is similar to that from Katrina (bottom), which extends further into the bay. (Photos courtesy of USGS) |

Before Hurricane Hugo swept through Georgia and the Carolinas in 1989, the insurance industry had never taken a $1-billion loss. Now, there have been several and the increasing residential and commercial development along coastlines and in hurricane and earthquake-prone areas promise even more. The damage to New Orleans and the complete scope of destruction along the Mississippi coast top offfor nowthe escalating cost and volume of losses from hurricanes during the last two decades.

Over the last 30 years, people and industry have migrated to hurricane country, lulled into what now appears to be a false sense of security fed by a period of reduced storm activity. And people continue to come. By 2025, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the population of the five Gulf Coast states will increase 72%, from 44.2 million people to over 61 million. Scientists now agree that another cyclic uptick has begun that will spawn more and greater storms, possibly over the next 50 years. Their effects will be compounded by the sea level that has been rising an estimated 2.2 millimeters per year.

Around the Gulf and up the Atlantic coast, officials and residents know they are vulnerable but they dont know where the next big one will hit. Still, planners can make an educated guess on the probability of getting hit by a major storm by plotting where tropical storms and hurricanes have made landfall on the U.S. mainland in the past. Weather service records show three areas that have taken the most hits: southern Florida, the Mississippi Delta and Cape Hatteras.

Hurricanes are fueled by very warm water, drawing strength from its energy. The warm-water Gulf and what is now known as its loop current is the furnace that fuels them. The current carries warm water from the Caribbean Sea, past the western tip of Cuba and into the Gulf. There, it works its way toward Louisiana. Without an outlet, it turns eastward and passes around the tip of south Florida and into the Atlantic where it combines with the Gulf Stream to carry warmer water up the eastern seaboard.

Some of the currents eddies hold water as hot as 80° F to depths of 300 ft. When a storm passes over such a current, it packs enough energy to gain Category 5 strength, with winds whipping to 165 mph. But there is not any uniform manner of protection for the cities, towns and land in their path.

"Its very doubtful that you can put some sort of blanket protection system in place," says Fred Caver, former deputy chief of civil works for the Army Corps of Engineers. "You immediately start running into local jurisdictional issues."

Limiting wind damage can be accomplished by stiffening building codes, as Florida did in 2002, some 10 years after Hurricane Andrew. But shoreline, geography and topography prevent any type of uniform system to protect against high seas and storm surges.

"We are protecting against water, wave topping and runoff," says Jeffrey C. Irving, program chief for the Army Corps of Engineers Norfolk (Va.) district. "While it doesnt sound like much, sand dunes can form a great berm that gradually slopes back into the ocean. Waves have to get past the beach before they get to whats behind it."

The Atlantic coast and part of the Gulf are peppered with barrier islands, natures first line of storm defense. Much of the Florida coast depends solely on dunes and beaches. Louisianas unique morass of wetlands and bayous provided a wide buffer to absorb and break the energy of strong storm surges. But they are degraded from channelization of the Mississippi River that prevents silt from replenishing wetlands through periodic flooding and the cutting of canals by the petroleum industry (ENR 9/12 p. 23).

|

| Tropical Storms passing near selected coastal points. |

"Comprehensive coastal zone management and watershed management is very important," says Dominic Izzo, vice president of DMJM+Harris in Houston and former Army deputy assistant secretary for civil works. "But there has to be some realization that sometimes youre really fighting nature and you dont have a chance to win."

Throughout the coastal U.S., people have built houses and businesses right up to the water line. "Theres just way too much construction too close to the danger zone," says Izzo. "The real problem is, everyone wants to be on the beach."

Two months after Katrina, Gulf Coast residents are just beginning to pick up their lives and communities. Planners, scientists and engineers are hoping to exploit and leverage the event into a more comprehensive policy to plan and protect people and property. Louisiana lawmakers want an unprecedented $250-billion plan that would, among other things, raise levees around New Orleans to protect against 165-mph winds and 30-ft storm surges from a Category 5 hurricane and replenish the states coastal wetlands. The bill also would give local officials unprecedented control over how the federal money is spent.

Observers give the bill little chance of being approved in its original form. But in neighboring Mississippi, Gov. Haley Barbour (R) sponsored a charette that could change the look of the states coast. Local officials and planners, architects and engineers will try to hammer out the beginnings of a plan to rebuild the coastal counties from scratch.

There are concerns in other regions, facing risks other than hurricanes. In Californias seismically active San Joaquin/ Sacramento River Delta, some 1,600 hundred miles of dikes and levees protect urban Sacramento and one of the nations most productive agricultural areas. But their age and differing standards of construction put the region at high risk. A 2004 levee break caused $100 million in damage, mostly to an agricultural area. Now, California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger (R) and state lawmakers are seeking a $10-billion bond to reinforce the system (see related story).

|

|

| Over the Top. Models predict Tampa could be swamped with even bigger storm surge. (Graphic top courtesy of Champs Laboratory; bottom by AP/Wideworld) |

Assessing Risk

As risks become greater, scientists are developing new tools to predict the intensity of storm surges and where they will land. Scott Hagen, an associate civil engineering professor who heads the University of Central Floridas Coastal Hydroscience Analysis, Modeling and Predictive Simulations Laboratory, recently ran a computer model showing that a Category 4 storm could cause a storm surge reaching 25 ft in Tampa Bay.

Tampa and neighboring Saint Petersburg are not immune to hurricane risks, but the region has avoided major damage for most of the past 35 years. But Hagen says predictions produced by the Advanced Circulation Model (ADCIRC) show storm surges reaching 25 ft from a storm moving at 15 mph with winds of 140 mph. He says cities will have to balance their risks of storm surges with costs of fortifying sea walls and levees.

Hagen says his team also is working with the Florida Dept. of Transportation to investigate scour from hurricane surges on bridge piers. "Extreme flow happens with hurricane surge," he says. "And when the surge rushes out, theres extreme velocity around bridge piers."

Hagens lab and others are working with the National Weather Service to produce an improved storm surge modeling tool than can be used for real-time forecasting, not just predictions. That effort will begin in early 2006.

"Right now, there is only one forecasting model," says Paul M. Scholz, chief of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminsitrations Coastal Services Center. Called SLOSH, it estimates surge heights and winds resulting from historical, hypothetical, or predicted hurricanes by taking into account pressure, size, forward speed and wind track.

Hagen says his team will push the model to include inland regions subject to innundation, down to the detail of individual roads and streets. "That can determine what areas you have flooding, areas likely to retain water and what bridges are in danger," he says. "We hope to improve upon information that evacuation planners have."

|  |

| |

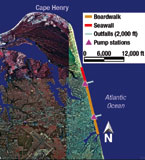

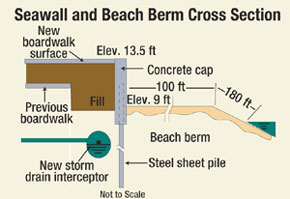

| Traditional Mix. Virginia Beach protection includes dunes, berms and storm walls with sheet pile foundations. | |

To protect Virginia Beach, Va., the Corps is finishing work on a $120-million, multiphase beach erosion and hurricane protection project. Begun in 1996, it includes three miles of 9-ft-tall, 300-ft-wide dunes connected to a 13.5-ft-high, 18-in.-thick, 3-mile-long concrete wall anchored by steel sheet piles. Completed in 2003, the dune and wall cover a six-mile stretch of boardwalk to provide 140-year flood protection. With about one more year of work, the project also includes installing seven pump stations and 6 miles of 48-in.-dia reinforced concrete pipe. The pipe is placed beneath the 58-block-long boardwalk and carries stormwater to a 2,000-ft-long ocean outfall.

"I believe strongly in beach replenishment, especially in areas already built up," says Caver. In areas like Virginia Beach, coastal Florida and developed barrier islands, beaches and dunes are all that separate development from storm surge.

|

| Barrier Flood. Outer Banks development flooded in 2003. |

In some of those places, such as Alabamas Dauphin Island or North Carolinas Outer Banks, the next big storm destroys the same structures. "The damage at Dauphin Island is similar to what happened after Hurricane Camille," says Orrin Pilkey, professor emeritus of geology at Duke University. "The first two or three rows [of houses are gone]. Its time to consider returning that to nature."

For areas where thats not possible, "the beach is the first and best protection against waves," says Izzo. "And in places like Miami, you dont have a choice. You have to keep the beach solid."

As hurricane season winds down, flood control proponents hope their efforts to push comprehensive solutions through Congress do not. Major events, like Katrina, open a window where such solutions may be vetted and approved in their entirety. The great Mississippi River flood of 1927 paved the way for raising the rivers levees. Planners and engineers now are working and waiting to see if long-term proj-ects like those recommended for Louisiana will finally be brought home.

urricane Katrinas pummeling of New Orleans and the coasts of Mississippi and Louisiana exposed the vulnerabilities and weaknesses of hurricane defense systems that go beyond the scope of engineering alone. As people and critical industries have concentrated themselves in the most exposed environments on the North American continent, the nations resolve to protect them through environmental measures or public works has lagged.