|

| Plug �n� Play? Repowering off-road vehicles takes months of research to engineer. |

On May 1, the thick morning fog began to lift off the San Fernando Valley, leaving a smoggy haze in its place. Two mechanics dressed in jeans and tee-shirts were preparing to drop a new 15-liter diesel engine into a 30-year-old scraping machine. Repowering old, polluting construction machinery is becoming a common practice in California as air quality districts place local restrictions on projects.

One thing about this scene was unusual, though. The operation was taking place not in a maintenance shop, but in the middle of a large jobsite. The 14.7-million-cu-yd earthmoving project in Porter Ranch, a development of new homes north of Los Angeles, has about a dozen scrapers gouging the earth there every day. Some have black plumes of smoke billowing out of them; some don’t.

A crane gently lowered the engine into the modified scraper frame. Putting in the new motor is part of a project to clean up emissions in the contractor’s fleet. Doing it in the field takes mechanics about a week rather than weeks at a dealership. “If we really push it, we can do it in three days with a lot of overtime,” says Eric Schmidt, a consultant in charge of the contractor’s program.

| + Enlarge this image |  |

Fresh Air

Fixing up old machines is not required by law, at least not yet. But Sukut Construction Inc., the general contractor that owns this fleet, has been repowering large earthmovers for about five years. Dealers needed weeks to do the work, so the company decided to engineer retrofits faster on its own. It hopes to get a step ahead of the competition should the public’s growing demand to cut diesel fumes escalate into a statewide mandate. The smoke signals are pointing in that direction, with California Air Resources Board, the state’s air quality regulator, on the case. It is in the middle of drafting a watershed ruling that scares contractors.

The rule calls for a ban on machinery that is more than 10 years old. It could render many millions of dollars of capital equipment worthless unless it is fitted with emission controls or repowered. Losing the asset value could put firms’ bonding in jeopardy, block financing and drive up construction costs. Regulators “could put the majority of contractors in California out of business,” says Mike Crawford, CEO of Santa Ana-based Sukut.

|

| Clearly Different. Visible fumes spew from the scraper on the right, which has original 1980 engine. The scraper on the left was repowered last year. CARB issued letter (below) to 79,000 contractors. |

Builders are confused, partly because rule drafts are sprawling and complex. Many “do not fully understand the implications of the regulations as they are currently proposed,” says Tom Holsman, CEO of the Associated General Contractors of California.

Suppliers stand to gain from the new rule. New equipment sales are likely to soar, and the $70-million-a-year diesel retrofit market in North America is expected to quadruple by 2010. Time is a factor. Users who buy new, clean diesels may have to wait years to get them. Producers “can’t make them fast enough,” says Crawford.

| + Enlarge this image |

|

Contractors question the ability of aftermarket suppliers to keep up, and price is a big issue. Retrofit devices are a low-cost solution to clean air but only eight devices meet U.S. and California standards for off-road diesels. Many exist for on-road trucks “but in terms of off-road, high-horsepower, there really isn’t anything suitable,” says Rick McCourt, Sukut’s safety director. CARB ranks devices by their level of effectiveness in reducing emissions, and only one device at CARB’s highest level is approved for more than one brand of construction machines.

Several new devices are being tested for verification, but suppliers have been slow to shell out $500,000 or more to do testing until they are sure of a market for their equipment, suppliers say.

California’s rule would open up the market. Air regulators acknowledge the dearth of emission controls but are confident that more are coming. “We are seeing a lot more on the horizon,” says Jim Blubaugh, manager of EPA’s National Clean Diesel Campaign. Beyond logistics, some question the legality of a mandate on in-use equipment.

Off-Road Retrofit Devices | ||||||

| Level | Supplier | Type of Device | Engine Models | PM Reduction | NOx Reduction | Fuel Type |

NA | Lubrizol Corp. | Fuel Emulsion | All | 17%-23% | 17%-20% | 500 ppm Diesel |

1 | Lubrizol Corp. | Diesel oxidation catalytic (DOC) | 1996-2002 (limited brands) | 25 | NA | 15 ppm diesel |

1 | Donaldson Co. Inc. | DOC | 1996-2003 (port equipment) | 25 | NA | 15 ppm or carb diesel |

1 | Extengine Transport Systems LLC | DOC + SELECTIVE catalytic reduction (SCR) | 1991-1995 (cummins 5.9-liter only) | 25 | 80 | 15 ppm/carb |

2 | Lubrizol Corp. | DOC | 1996-2002 (limited brands) | 50 | 20 | emulsified |

3 | Lubrizol Corp. | Diesel Particulate filter (DPF) | 1996-2004 | 85 | na | 15 ppm/carb |

3 | Cleaire Advanced Emission Controls LLC | DPF | 1996-2003 (emergency generators only) | 85 | na | 15 ppm |

3 | Caterpillar Inc. | DPF | 1996-2005 (Caterpillar 175-300 hp only) | 89 | NA | 15 ppm |

Source: EPA, carb. All devices verified to meet federal and california standards. | ||||||

Vague Legislation?

While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulates new engines, it says it has little authority to regulate existing, “in-use” engines. But states may be able to mandate cleanup as long as their regulations are constitutional and federal officials sign off on them, says EPA.

“Our attorneys have spent a lot of time with this issue and they are confident that regulating in-use equipment is legally defensible and justified,” says Ron Nunes, a CARB engineer. Others think the proposed law is too vague. “I’m not sure that has been evaluated in the courts or clearly by EPA,” says Allen Schaeffer, executive director of the Diesel Technology Forum, a trade group in Frederick, Md.

Industry insiders say they may try to block the rule if it is problematic. So far, no challengers have come forward. In the meantime, California regulators have held workshops with contractors to gather input. “CARB has been working cooperatively with us,” says AGC’s Holsman. “There is no sign at this time that we are intended to take any kind of legal action.”

If the air agency issues the regulation next year as expected, it would be the first mandate of its kind in the U.S. Contractors would need to upgrade existing fleets to match EPA standards for engines manufactured in 2015, a deadline commonly known as “Tier 4.” A phase-in period would begin as early as 2008 and continue through 2020.

New retrofit devices, engines or both would be added every few years as cleaner ones become available. Owners also could meet “fleet averaging” standards, where some older machines could operate without retrofits, but it would be illegal to buy or sell them.

Diesel’s Dirty Legacy

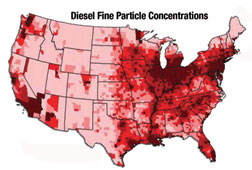

Nationwide, there are fewer construction machines in operation than the millions of diesel trucks, buses and other vehicles combined, according to EPA. But today’s two million construction diesels make up a hefty share of toxic air pollutants around the country—about one-third—because many were built before EPA regulations. In California, construction emits about half of the off-road diesel toxins in the state, with about 160,000 vehicles in use, according to estimates.

Some jurisdictions across the U.S. are tackling the problem by writing air-quality requirements into contract specifications. “They are all pushing us that way,” says John Robinson, an estimator at Kenny Construction Co. in Wheeling, Ill. New York City has a new law requiring clean fuels and retrofits on city contracts. In the Midwest, the $6.6-billion O’Hare Modernization Program in Chicago is requiring cleaner, ultra-low-sulfur diesel fuel (ULSD) and diesel oxidation catalysts (DOCs) on mobile equipment.

|

| Congested. Dan Ryan reconstruction in the Midwest has clean fuel and retrofit requirements. |

State agencies, such as the Illinois Dept. of Transportation, also are having contractors fill up with clean fuel, such as on the $600-million Dan Ryan expressway reconstruction in Chicago. “There are five to six schools immediately adjacent to the project,” says IDOT Secretary Tim Martin. “We wanted to make it an environmentally superb contract.” The lungs of children are especially vulnerable to diesel fumes, scientists say.

Domestic diesel cleanup generally lags Europe. In Switzerland, more than 6,000 construction machines have been retrofitted with particle traps and diesel particulate filters (DPFs) since the country issued a retrofit ordinance in 1998.

In the U.S., the retrofit movement has bubbled up slowly over the past 10 years. One of the first major projects to use controls was the Central Artery/Tunnel in Boston, where contractors installed more than 100 DOCs in the 1990s. Some machines ran on emulsified fuel, which has a water mix to lower combustion temperatures. Catalysts and additives cut nitrogen oxide pollution (NOx), an ozone contributor and lung irritant.

Federal regulations for off-road machinery are focused on NOx reductions and diesel particulate matter (PM), But construction machines have much longer life spans than cars and trucks. The benefits of federal rules probably won’t come to fruition until 2030, according to environmentalists, who want PM cuts to happen faster.

California says diesel PM is a carcinogen and plans to cut it down by 85% in 2020. Regulators want to “reduce diesel PM emissions by the greatest amount as we can in the most reasonable amount of time,” Nunes says. Construction firms say they need cash to do it.

|

| Hands On. A mechanic welds a bumper after installing a Tier 3 engine into a 1978 scraper. |

Shaking the Money Tree

Voluntary retrofit programs are flourishing nationwide, enticing construction firms to apply for grants. For Sukut’s single-engine scrapers, the cost to repower tops out at $120,000. It receives money from a state agency that kicks in $96,000. “They are picking up almost two-thirds of the cost of repowering a machine,” says Mike Ortiz, president of Sukut Equipment Inc., the contractor’s in-house rental fleet. “A lot of times, we’re the spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine go down,” says Raymond Gorski, an advisor for the Mobile Source Air Pollution Reduction Review Committee (MSRC), which distributes grants to Los Angeles contractors, including Sukut, from motor vehicle registration fees. Many such programs are active around the country. There is one drawback to grant programs, however: Once retrofits and repowers are required by law, grant money no longer is available.

For now, repowers are one of the most cost-effective ways to reduce particle emissions. “It is emerging as being one of the prime strategies,” says EPA’s Blubaugh. Many contractors believe the work is worth the trouble because the new engines are easier to service. But the up-front costs are still frightening. “We are using as much capital as we can afford to upgrade our engines,” says Crawford. He adds: “That is going to be the price of admission to stay in this business.”

(Photo 5th from top courtesy of Pukelis & Lehrer Communications Inc., all other photos by Tudor Hampton for ENR)