The Seabees have always said, "We build, we fight," but more often than not the emphasis is on construction instead of combat. Still, a Seabees recon team supporting the 2nd Marine Division's push toward Baghdad found itself in a hot zone in the Euphrates-Tigris River Valley. SERT-5, from Port Hueneme, Calif., is thought to be the first Seabee unit to face hostile fire since Vietnam.

|

| Destroyed Iraqi military equipment litters countryside. (Photo courtesy of SERT-5) |

SERTs, Seabee Engineer Reconnaissance Teams, perform quick evaluations of field site conditions, usually regarding roads and bridges. Their job is to gather intelligence. They help determine what measures and equipment will be needed to "fill in the gap." As soon as the front-line combat units push forward, the second wave of troops and materiel should flow forward into secured areas.

If front-line combat engineers need to cross a river, often they'll call for an Engineering Support Battalion to "splash" or place a floating bridge to enable passage. ESB will dismantle it as soon as possible and move forward to the next crossing. The third wave, or rear-guard, engineers from the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force Engineering Group (MEG) then place non-standard bridging that can handle 70-ton loads. This would include loaded fuel and water tankers or Abrams tanks.

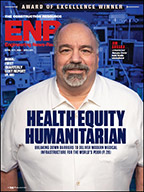

|

| Chief Warrant Officer Matthew Kiefer led recon team. (Photo courtesy of SERT-5) |

"We'll look for a suitable adjacent site to the floating bridge," says Chief Warrant Officer Matthew Kiefer. "We'll also do route assessments, looking for quarries, cement batch plants, equipmentanything that can be used for road, bridge and camp construction. Then we look for a staging area." The goal is to enable mobility as quickly as possible for the main force.

"A battalion has a big footprint," adds Equipment Operator Second Class Craig Ray, South Bend, Ind., His specialty is route analysis. "Any intel we can provide benefits them way ahead."

Typically there are 10 people in a team, split into three elements: reconnaissance, security and liaison. Collected field intelligence is quickly put into a digital format, usually text or JPEG files, then downloaded to a computer and transmitted to the rear via a high-frequency data stream. The MEG can then develop a game plan in the field. For more complicated projects, the MEG can "reach back" to Pacific Division engineers in Honolulu for detailed recommendations.

SERT-5 formed in December and deployed to Kuwait. "We trained together, lived together, and slept together, until we functioned as a unit," says Kiefer. The group became part of Task Force Tarawa. This gave them two weeks of final training with elements of the 2nd Marine Division. When the war started on March 20, the Army's Third Infantry Division raced up the left flank along the Euphrates River. British troops concentrated on Basra, the second largest city in Iraq. They besieged the city and begin the arduous job of house-to-house fighting. The 1st Marine Division swept forward on the right flank, following the Tigris. The 2nd Division the spear point of Tarawa, with SERT-5 in tow, took the middle.

"We just in a gagglethousands of vehicles moving across the desert in a gaggle," says Kiefer. The British met stiff resistance in Basra, besieged the city and settled into a pattern of block to block close combat. Task Force Tarawa, encountered its strongest opposition the first 10 days around An Nasiriyah, encountering armed resistance, sporadic sniping and a car-bomb ambush.

"When we came through An Nasiriyah, Tarawa had been through the night before. They got hit pretty hard," says Kiefer. "We were monitoring the tac nets (radio transmissions). It was intense. One would say, We've got six wounded, so many killed.' Another would come back with We're doing this. We've got [a few people] wounded.' It was a hot zone, but everyone sounded really calm."

SERT-5 was augmented by a three-man Underwater Construction Team. The recon unit now carried gear necessary to work the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and the Saddam irrigation canal: scuba tanks, zodiacs--even a soil penetrometer. But the push was moving too quickly for detailed analysis, says Personnel Manager Second Class Gary Husdon, Ft. Lauderdale, Fla. He is member of the liaison crew. In training "we work in terms of a 96-hour window, with a plan that can be defined and redefined. There's a lot of preplanning. But once we started rolling there wasn't much opportunity to ado detailed analysis."

"It wasn't possible to stop to go under the bridges," says Ray. "A quick visual [indicated] that everything was MLC 70 (Military Load Class 70 tons), so our mission kind of dwindled. But the situation prevented SERT-5 from dropping back or even waiting in place for support units to move up. Although organized Republican Guard units turned tail early on, irregular Iraqi fighters continued to throw down sporadic mortar and small arms fire. "I didn't really think they were firing at me," says Kiefer. "It was surreal."

Whenever opposition revealed itself, close air support was immediate and overwhelming. Cobra and Apache helicopters raked the area with Hellfire missiles and machine gun fire. "The U.S. forces were too much for them," says Ray. Seabees and Marines often indulge in sibling rough humor: Seabees say they're skilled tradespeople, too smart to be ground-pounders. Marines say Seabees should stick to nail guns instead of M-16s. But now, says Ray, "I have a new respect for the Marines. They are warriors."

|

| Seabees relax after combat mission. (Photo by Andrew G. Wright for ENR) |

Being shot at, rolling through a battle zone and seeing the overwhelming retaliatory response was a sobering experience. After the Marines took casualties at An Nasiriyah, the tenor changed. "We were forced to play a card," says Hudson. "The Marines became a little more forthright."

None of the men was anxious to go into specifics of the damage they saw inflicted. Their photographs tell more than their words: helicopters hovering with a black smoke cloud on the horizon, enemy prisoners of war under guard, a charred pickup truck with the remains of an antiaircraft gun still on the bed. "I saw a lot of carnage," says Kiefer.

SERT-5 team leader Lt. Bill Windus, Somerville, N.J., says only, "We went to do engineering, but the only engineering to be done was way up the road. I saw stuff I won't talk about for a long, long time. If ever."

SERT-5 left for home on April 6.

![]()

|

ENR Managing Senior Editor Andrew G. Wright is in Baghdad

with the Engineer Brigade of U.S. Army's Third Infantry

Division.