The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers hopes to use water diversion structures to push water out of sensitive wetland areas and keep away oil that has been drawing near shore since the April 20 explosion of the Deepwater Horizon rig about 50 miles off the Louisiana coast.

In essence, the Corps is investigating if the rains behind the Nashville flood could help save the Louisiana Coast from the disastrous oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

The unprecedented oil spill is subject to rough winds and tidal flows. Faced with these complications, Chuck Shadie, the Mississippi Valley Division head of water control, asked the U.S. Army’s Engineering Research and Development Center in Vicksburg, Miss. to perform hydraulic modeling.

The modeling will determine if opening the flow to full capacity on some Corps water diversion projects might push water away from sensitive wetland areas and actually buffer against incoming oil flow.

“At this point, we don’t know, but we’re trying to develop modeling of what the oil might do if we open the diversions to maximum flow,” says Bob Anderson, public affairs officer, MVD.

The recent, 1,000-year Ohio River Valley rain event that is causing so much flooding in Tennessee and Kentucky is expected to make its way into the New Orleans area by May 18, doubling the current Mississippi River flow to 1 million cfs.

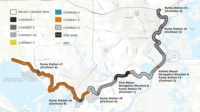

Specifically, the Corps is looking at the potential impact of the Caernarvon (currently at maximum 10,000 cubic ft. per second) and Davis Pond (maximum 8,000 cfs) freshwater diversion sites.

The initial results were not promising. “Based on preliminary modeling, it looks like the current winds and tidal wave action will offset any good the added flow from the diversions might make,” Anderson said on the morning of May 5.

The state would make the decision on whether or not to operate the diversions, but the Corps is working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to model oil flow rates and perform hydraulic modeling to advise about water flows and salinity levels if the diversions were opened.

“We’re also looking at how we can equate the impacts of opening the diversions to the number of acres protected,” Anderson says.

Additionally, the Corps is beginning modeling on the possible benefits/consequences of opening the Bonnet Carre Spillway.

The heavy rains to the north may provide an opportunity to save the coast.

The normal trigger to open the Bonnet Carre spillway is a flow of 1.25 million cfs, but the Corps is looking at whether an earlier opening may help push the oil away from shore.

“First of all we want to know if it will have any impact on the spill and, if it pushes the oil away, where it would push it to,” Anderson says. The Corps is also considering the impact of opening the spillway on the supply of clay borrow material that is being harvested there for ongoing levee work in New Orleans.

“We need to know if it will have only a negligible impact on oil and shut down construction,” Anderson says.

Meanwhile, contractors are watching and waiting to determine how the spill will affect the progress of projects underway in the Gulf Coast area. “Right now our primary concern is the potential for impact to shipping of precast caps from Mississippi,” says Charlie Hess, senior vice president for Shaw Environmental & Infrastructure Group, Baton Rouge, La. and prime contractor on the $1.3 billion Lake Borgne Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Storm Surge Barrier.

Currently the Southwest Pass and Lower Mississippi River are open to navigation with “no expectations to restrict navigation,” according to a May 4 report by the U.S. Coast Guard Sector New Orleans coordination team. Shipping lanes from Mobile, Ala. were projected to remain clear and there were no reports of oil coming into the SWP, says Ken Holder, director of public affairs for the NOD of the Corps, which is part of the team. NOAA trajectories indicate beached oil along the eastern shoreline of SWP and eastward, but none had been reported by the 1300 hours May 4 meeting. Associated Branch (Bar) Pilots received one report of oil sheen in the Fairway Anchorage located in the Gulf of Mexico, about 5 miles southeast of SWP.

The USCG has set up vessel cleaning stations at Boothville, Venice, Port Fourchon and Empire Locks (all in Louisiana). Vessel masters have been asked to observe their vessels and request hull cleaning if they see a sheen.

Dredging efforts in SWP have not been affected, Holder adds, but oil detection kits will be distributed to dredges this week.