Steel Sector Plans Paradigm Shift 4/14/2003

|

| CHANGE SEEKERS Task force's Carrato (l.), Engler, Holland. |

The American Institute of Steel Construction Inc. predicts that, thanks to electronic data interchange, in 15 years at most, two-dimensional design and shop drawings will be relics of a bygone era, pushed aside by three-dimensional models. AISC is pushing hard to catalyze this paradigm shift, starting with the steel sector. But like David going against Goliath, it has its work cut out for it. Resistance to change in the way buildings are delivered, especially from architects and even structural engineers and construction managers, is palpable.

"With the steel sector leading the way, we hope that 3-D models will eventually replace traditional 2-D drawings as contract deliverables," said Gabe Coleman, AISC's director of information technology initiatives, at the Chicago-based group's North American Steel Construction Conference, April 2-5, in Baltimore. The meeting had 2,350 fabricators, engineers, detailers, erectors, suppliers and educators in attendance. Coleman predicts that the paradigm shift will take five years for steel and another five or 10 years for the total building package.

The vision for the future is one in which the owner or developer of a building owns a complete project database, including the 3-D model, shared by designers, builders and facilities managers through the service life of a building.

While it may take more than a decade for EDI to totally permeate the building sector, change in the steel sector is well along. Yet even with steel frames, AISC is beginning to see the bigger picturethe need to get the owner and architect on board, not just the structural engineer. The institute is planning to reach out to their representative groups through a new task force created to develop an EDI business model for steel.

"Because of the changes in technology, we can make a fundamental change to the work process," said Mark V. Holland, task force leader and chief engineer for fabricator Paxton & Vierling Steel, Omaha, at a session on electronic data interchange (EDI). "The sharing of the model is the backbone of the change," he added.

The first step, however, is to to develop contract language for the exchange of 3-D models as contract deliverables. The language developed will be incorporated into the code of standard practice in the AISC's 2005 Unified Manual of Steel Construction.

"Business models don't support EDI," said Don Engler, task force member and vice president of international operations for BDS Steel Detailers, Mesa, Ariz. "We haven't figured out the proper business model with the architect on board. That's the "real impedance" to this in the commercial sector, he adds, and one of the problems the task force plans to tackle. Its first meeting is slated for late spring.

"AISC is hitting the upstream side," said Peter J. Carrato, task force member and principal civil engineer in the Frederick, Md., office of Bechtel Power Corp. "There is a wide-open area for using this in procurement and construction," he adds, predicting it will be more common in the future. "We're feeling our way through it, but it's easy in Bechtel's engineer-procure-construct arena because you don't have architects and contractors to deal with."

The resistance is not only from the architect and contractor. "The problem is educating the existing work force," says Ivan Jivkov, senior designer with civil-structural engineer, Hatch, Montreal.

Regardless, Carrato thinks that "we're only scratching the surface with the power of these tools," which he says add so much value to the project.

Proponents say that using 3-D modeling and EDI on a project can save time and money while increasing the quality of the end-product.

The EDI process works if the engineer can export the 3-D analysis model into the design model, which it then shares with the fabricator for connection design and detailing. The detailed model is then exported upstream to the designers for approval. It then goes back to the fabricator, which uses the model to drive computer-numerically controlled equipment. The model can also be exported into the fabricator's management information system software for resource planning and other business. The steel erector also uses the model to produce the erection sequence.

The schedule is shortened because design and detailing overlap, steel can often be ordered earlier, the shop drawing phase is eliminated and the model approval phase takes less time.

An EDI project using design-build, which steel experts agree is currently the best delivery system for EDI, can take almost 50% less time from preliminary design to the start of steel erection than a 2-D, design-bid-build job, according to AISC. There are also savings in the 3-D model approach using design-bid-build, report sources.

Click here to view chart

Click here to view chart

Potentially, sharing of a 3-D model reduces requests for information, the time and expense involved in tracking them and the time lost waiting for answers. "Some 50% of a project's time is spent on questions about incomplete information," said Chris Moor, North American sales manager in the Atlanta office of Tekla Inc., which produces the Xsteel design and detailing software used on Chicago's Soldier Field football stadium now under construction.

"People in the industrythe whole supply chainstill don't understand what they can achieve" with shared 3-D models, added Moor. "With the transfer of a 3-D model the communication is so much improved."

Firms like Bechtel and Fluor have been using 3-D models for engineering, procurement and construction for years. In the commercial buildings sector, say sources, development of a 3-D approach requires a radical shift in the work flow, especially between the architect and the structural engineer but even between the fabricator and the design team.  Click here to view chart

Click here to view chart

To create the model in the first place, engineers need to get accurate dimensional, orientation and geometric data from the architect during design development. It's not easy to get. "If you force design to very specific dimensions early on, it is hard to modify it in 3-D," said Anthony O. Montalto, an associate with architect Wood & Zapata, Boston, which is working on Soldier Field. "3-D begins limiting the architect's palette."

Even for steel buildings, there are so many bugs to work out of the business model. One big question is which entity "owns" and is responsible for the model. Another is which entity is in charge of the model's care and feeding throughout the project. "We need a new entity to manage the model," says Sid Dickerson, senior vice president in the Irving, Texas office of Hirschfeld Steel Co. Inc., Soldier Field's fabricator. He suggested calling this entity a steel construction manager. The deliverable would be the electronic equivalent of maintaining a record set of documents, says Dickerson.

|

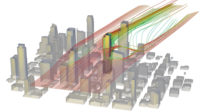

| NUTS, BOLTS, BEAMS Detailed 3-D models show complete frames. |

Lanny J. Flynn, principal in charge of design-build for structural engineer Putnam Collins Scott Associates, Tacoma, Wash., thinks the way to save time with the 3-D model approach is for the structural engineer to take responsibility for connection detailing. On a 270,000-sq-ft high school project in Tacoma, the fabricator was awarded the contract on or about Jan. 24, and steel erection is already about a third complete, he said.

AISC is on the launch pad of its second big push toward EDI. The first, which began in 1999, was an effort to get analysis, design and detailing software developers, including Tekla and its competitor, the Gaithersburg, Md.-based designData, which produces SDS/2 software, to adopt a uniform standard so that the different analysis, design and detailing packages could "talk" to each other. The so-called CIMsteel Integration Standards/2 (CIS2) is now established as common translator.

The tools are there, says Coleman. The next step is to convince the members of the building team to use them.