Winning the 'War for Talent' is Key Challenge in Growing Industry, Says New FMI Report

|

In a new twist on a familiar subject, FMI Corp. has for the first time broadened its traditional analysis of construction firm training practices to focus on the more critical challenge of talent development in a growing but worker-strapped industry.

The Denver-based management consulting firm’s report, issued in April, outlines how firms are faring in the “war for talent,” and how they can develop a more successful battle plan. “Is it possible to create and maintain a talent-focused culture while building employee commitment?” the researchers ask. “The answer is yes, but not without hard work, a clear vision and supporting strategies.”

Photo: Report outlines some successful approaches.

|

FMI collected data from more than 50 construction company executives in a cross-section of industry sectors, firm sizes and regions. Half of the respondents are general contractors, 43% are in firms with annual revenue between $100 and $400 million, and 37% are in companies with peak employment of 100 to 500. Most respondents are in human resource or training roles, but about 15% are presidents or CEOs.

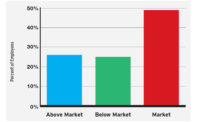

The executives’ responses paint a bleak picture for construction firm staffing in the next 10 years, projecting a 34% loss of top executives, 24% of senior managers, 21% of project managers and 28% of field managers.

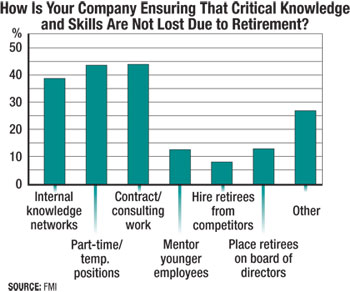

Employee retention is a key struggle, says Kelley Chisholm, FMI talent development consultant and survey author. “Firms are not offering phased retirement and they are not laying out clear career paths for employees,” she says, noting that only 16% of respondents offer the former and only 11.6% the latter. “Firms attract people into their company but do not provide a clear path, so employees might not want to stay if they don’t know where they are going to be five years down the road,” Chisholm says.

Industry companies are taking some steps in the right direction to improve retention, FMI contends. About 82% of respondents say they are budgeting for training activities in 2007, versus only 54% in 2003. “One of the most important methods of retention is to train and develop employees,” says Chisholm. With the cost of replacement and training as high as 2.5 times a departed worker’s salary, the economic incentive to improve retention rates is high, she points out.

| "Most people don�t leave their companies, they leave their bosses." — Richard Condit, Sundt |

Chisholm highlights some successful approaches that Sundt Construction Inc., Tempe, Ariz., has adopted. The firm has used training to improve retention beyond simple individual improvement. “Most people don’t leave their company, they leave their boss,” says Richard Condit, senior vice president and chief administrative officer. Sundt provides extensive training for supervisors to ensure that their subordinates are engaged and happy, resulting in better retention and performance, he says.

Sundt uses Gallup Consulting’s Q12, an engagement survey, to ensure that its employees are actively engaged in their work. “You need to get employees into roles where they are using their strengths every day,” says Condit. “The front end is the key.”

In addition to improving retention, Sundt uses training to meet the generational gap in its workforce. The firm’s Leadership Excellence Accelerates Performance program (LEAP) fast-tracks young employees into more advanced roles. “We have baby boomers going out and very talented people coming behind, but there is a generational gap. The Gen X and Yers want more responsibility sooner, so it works well,” says Condit.

| "3D modeling is sexy. If we market it, we can become more attractive to kids" — Charles Thornton, Consultant |

But the construction industry also must keep that people pipeline flowing. “The problem with construction is that it has always been the most fragmented industry in the U.S,” says Charles H. Thornton, founding principal of Thornton-Tomasetti, New York City and now chairman of Charles H. Thornton and Co., Easton, Md.

Without a unified effort to appeal to students, the industry’s image has suffered. “The war we now have for talent may be a result of our poor leadership,” says Ralph Locurcio, retired brigadier general with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and now an engineering professor at Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne. “We’ve failed to attract people to our profession.”

Thornton’s efforts to help improve construction’s image through the “ACE” mentor program, which pairs groups of 15 to 20 high school students with a team of six or seven industry mentors, has shown some success. Mentors range from building trades to architects and they meet with students up to 18 times during the school year, teaching them various industry elements and collaborating on projects.

The program has increased its numbers dramatically, growing from nine locations in 2002 to 93 today, and reaching more than 30,000 students. “There are 73 locations that want to start a program,” says Pam Mullender, ACE program executive director. Participants aim to reach 70,000 students over the next five years. “We are have a meeting on June 14 to make the governance changes necessary to make this growth happen,” Thornton says. Partnerships with groups such as the American Institute of Architects and The Associated General Contractors will help.

|

“The power of ACE is that we represent the entire industry,” says Thornton. “We cover the entire spectrum of jobs with the students and let them know how much money they could earn with each.”

Technology advances in construction such as building information modeling (BIM) hold great potential for improving its image, says Thornton. “3D modeling is sexy. If our industry markets this technology, we can become more attractive to kids. If guidance counselors understood how much computer technology is used in construction, they would not be sending the kids to the programmers,” he says.

BIM also will boost productivity and ease labor challenges, says Thornton. “I believe we will move towards assemblage,” he says. “With building information modeling, you can do 3D modeling of rebar cages and have robots prefab them off site. One reason our industry is so backward is that the cost of construction has been acceptable. With costs exceeding $1,000 per sq ft in many areas, it doesn’t pan out.”

|

The FMI study contends that the industry still has room for improvement in efforts to attract new blood. Only 51% of respondents are recruiting non-traditional labor sources, such as women, minorities, non-violent offenders and military veterans. Today, 92% of management personnel is white. Only 10% are women. As baby boomers retire and the workforce changes, the industry will need to diversify if it hopes to fill positions, says Chisholm.

The researcher also points to Skanska USA Civil, Whitestone, N.Y., as another pioneer in workforce development. Skanska initiated its Core Competency Training Program in 2004, aiming to boost its young employees. “We want to develop the careers of our entry-level engineers and make sure that they have a true understanding of all of the functions of an engineer in construction,” says Larry Bolyard, director of human resources.

There are six core competencies in the program: assistant superintendent, estimating, engineering, cost scheduling, safety and office/field engineer. Each young engineer spends six months working in each group with a senior executive mentor. The first class will complete the three-year program this summer with great results, says Bolyard.

The program also allows Skanska to identify strengths and weaknesses of each employee, so that they can be placed in the right positions. The program is also very inexpensive, says Bolyard, noting that its minimal cost is repaid by expected productivity increases. “Our retention rates for young engineers have increased and we are grooming our future leaders,” he says. “Leaders rise to the top quickly, so they are easy to identify.”