Risk in Construction 2015

In a Good Year, Problem Projects and Much To Be Wary Of

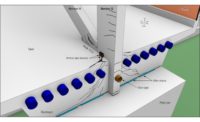

Deep girders on an Edmonton bridge underwent tortional lateral buckling and had to be removed for testing, delaying completion. Photo: Earthcam.

First, let’s look at the bright side of 2015.

Sales and revenue ticked steadily higher, and insurance and bonding capacity was plentiful. It seemed that fewer bankruptcy attorneys, the industry’s morticians, had to be called to lay to rest big contractors that, having outlived the recession, failed to survive the recovery. At the jobsites, there were grimly familiar accidents and also the ghastly Mecca crane tragedy of Sept. 11, over which the Saudi government has indicted five engineers. Yet there was plenty of safe work, too. Ironworkers settled without incident long girders atop piers at the new New York bridge that will chain the banks of the Hudson River.

If you had skill in a construction trade, you were feeling more love from employers, whose biggest worry wasn’t necessarily whether they would win the bid, but whether, if they did, they could staff the job. Wages edged higher, and welders’ base salary came to $65,000, not counting benefits or bonuses, said a survey by the NCCER, which accredits craft training programs.

Still, 2015 felt to be the kind of year in which, if anything could happen to make competition tougher, regulation trickier and liability more perilous for designers and contractors, it would.

For example, has any U.S.-based international engineer or contractor lost out to a state-sponsored competitor from China or the Middle East? Some companies said that was a concern.

And has any contractor had to try to negotiate away a contract clause where, if the owner is not satisfied with the work, the contractor is obliged to tear down what it has built and restore the site to greenfield condition?

That clause has been spotted in a proposed contract, too.

New Federal Regulations

For contractors on federally funded projects, new and proposed regulations expanded the compliance worries. The new and proposed rules include, according to an article in the ConsensusDocs Construction Law Newsletter, mandatory reporting of prior regulatory violations, limits on arbitration and requirements to disclose what the contractor pays staff.

Haywire public works projects, as has happened before, garnered a lot of attention.

In June, the legal contest commenced over Bertha, the tunnel-boring machine in Seattle that had to go back to the shop after striking a pipe and hasn’t done any work for 18 months. The stakes in this preliminary phase over what went wrong aren’t yet about differing site conditions. Instead, a disputed $85-million builders’ risk insurance claim turns on the issue of whether, as the insurers contend, the TBM was under-designed.

Contractor Seattle Tunnel Partners appeared to have triumphed over the insurers in the early debate over venue selection, which seems to be set for Seattle.

In Boston, where bad memories of the Big Dig remain vivid, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority earlier this month terminated for convenience the contracting team on its new Green Line commuter surface rail system extension. MBTA had hired the joint venture of White-Kiewit-Skanska on what was called a CM/GC delivery system, which involved no overall guaranteed price and functioned apparently much like a cost-plus contract (and may have been a better idea when, and if, the scope was not fixed or known). Now that project “overruns” are in the hundreds of millions, MBTA has called for a do-over and will apparently seek a firm fixed price.

The most striking image of a problem project, however, came from webcam photos out of Edmonton. There, during erection in March, several deep girders framing a comparatively simple steel bridge over a busy avenue buckled suddenly, like so many strips of bacon (U.S.-style). That, and another much bigger Edmonton bridge with steel fabrication and delivery issues, provided a trying 2015 for the city’s road design and construction manager, Barry Belcourt. Both projects are delayed by about a year.

Apple Parts With Skanska-DPR

The private sector had its own high-profile partings of the ways.

A joint venture of Skanska and DPR ended its role as general contractor of Apple’s ring-shaped new headquarters in Cupertino, Calif. Exactly what the differences were is unknown, but there’s a good chance it had to do with price, scope and schedule. Exactly where the deal fell apart isn’t known, either, but there were no lawsuits. Rudolph and Sletten, a division of Tutor Perini, was expected to complete the core and shell of the main building instead of Skanska-DPR.

In the often-troubled field of nuclear power construction, problems triggered the sale of an entire construction unit along with its projects. Chicago Bridge & Iron on Oct. 27 said it would sell its nuclear construction business in the U.S. and China, including its troubled Summer and Vogtle plants in South Carolina and Georgia, respectively, to Westinghouse Electric. Fluor Corp. will take over the construction work.

Under the terms of the overall $229-million deal, Westinghouse will pay CB&I $161 million after Westinghouse substantially completes work on eight reactors that the two firms had been working on together. It will take until next year, perhaps, to find out if indemnifications were involved.

Analysts could not decide who the winners and losers would be in this complex transaction, and it wasn’t clear how penalties, including liquidated damages, figured into the thinking. In 2016 it should become clearer who got the better bargain.