A New National Partnership Aims to Reduce Number of Construction Industry Suicides

A national partnership of industry leaders and suicide-prevention experts launches an initiative to save lives

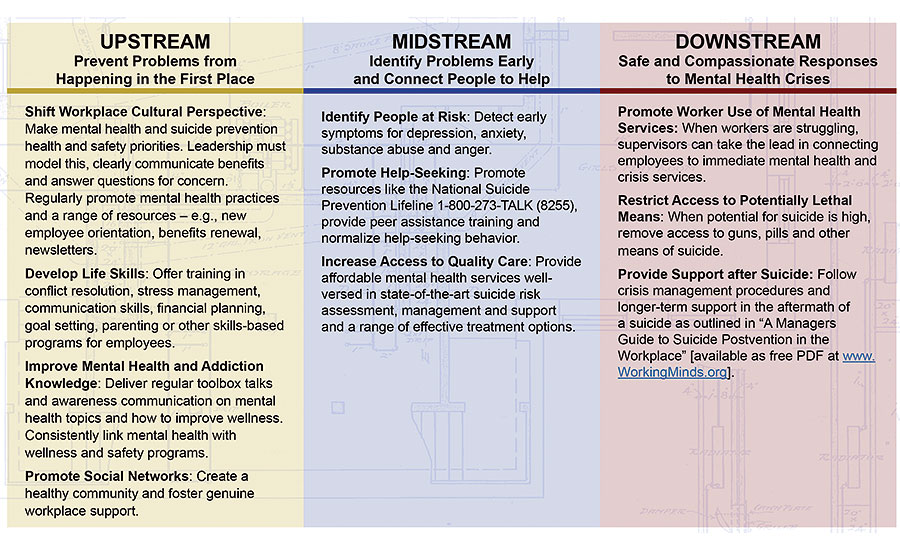

The key steps in suicide prevention are recognizing problems early on, identifying possible causes and connecting employees with resources and help.

CHART COURTESY OF “A CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY BLUEPRINT”

Construction ranks among the top nine occupations with the highest risk for suicide, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Demanding physical work, coupled with the stresses of seasonal employment and minimal access to mental health care, often create a workforce vulnerable to mental health challenges like depression, substance abuse and suicidal thoughts,” says leading suicide-prevention expert Sally Spencer-Thomas. She is CEO and co-founder of the Carson J. Spencer Foundation, a Colorado-based nonprofit that is finding innovative ways to make suicide prevention a priority in the workplace.

“Everybody knows someone affected by suicide,” says Cal Beyer, director of risk management for asphalt paving company Lakeside Industries in Issaquah, Wash. “It’s a real, everyday occurrence [that has typically been] swept under the carpet because nobody wants to talk about it.”

Beyer, who serves as the construction industry representative to the Workplace Task Force for the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, has been an industrial specialist in risk and safety for 25 years and dedicated to construction since 1996. For the past several years, he has worked to make conversations about mental health and suicide awareness part of the everyday vernacular on construction sites.

Suicide cuts across all segments and industries. The rate of suicide is highest in middle-aged white men, and men die of suicide 3.5 times more often than women, says the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among men aged 25-54, Beyer says, with 42,000 deaths by suicide each year—more than the number of deaths due to car accidents. But no one is talking about it due to a wall of shame and silence, he adds.

Beyer recently summarized current efforts and industry support for the issue at a meeting with the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services in Washington, D.C. He also participated in a health dialogue to address mental health and suicide prevention strategies in the workplace. The forum was hosted by the White House, with the U.S. surgeon general and selected cabinet secretaries and staff in attendance. Beyer says that as more people talk openly about this issue, more business leaders will begin to take action on mental health and suicide risks in their own companies.

Guidance and Support

Spencer-Thomas says construction workplaces tend to have a strong culture of machismo and stoicism, “but when [workers] experience a significant challenge like divorce or health issues or trauma, they tend to suffer in silence in an attempt to push their way through it. And we know that like other health conditions, when they go unchecked, they tend to get worse, not better,” she says.

“In police and fire departments, post-traumatic stress and grief counseling is made available as part of the job, but this isn’t happening in construction, where the message is: ‘Get over it tough guy,’ ” Beyer says.

Mental health experts say that construction companies need help in implementing coping strategies. “We must give employees reasons for hope, then offer support through employee assistance programs,” Beyer adds. “But first, we have to recognize when people are struggling.”

“The tough-guy culture in construction certainly makes for rugged employees, but when people are overwhelmed by chronic pain, job uncertainty or mental health problems like depression or substance abuse, that tough exterior can prevent workers from reaching out and getting much needed support and treatment,” Spencer-Thomas adds.

She says that in order to change a company’s culture and encourage dialogue around this issue, “We start by finding those bold visionary, influential leaders who are willing to step into this effort—along with HR managers, safety directors, etc.—and help them create a strategy they can implement into all their practices.”

Jon Kinning, chief operating officer and executive vice president for Denver-based RK Mechanical, embraces his role in speaking out about mental health and suicide prevention to the company’s more than 1,000 employees. Kinning, who has experienced the suicides of both a family member and an employee, says that when the highest level in an organization is talking about mental health and suicide, a firm can “really move the needle” on the issue.

Today, RK is working to prevent construction suicides, holding workshops and conducting sensitivity training for employees as a part of its wellness program. “When an owner talks, they’re talking through a megaphone,” Kinning says.

New Blueprint Offers Tools

The Carson J. Spencer Foundation, in partnership with RK Mechanical and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, has jointly released a suicide prevention guide entitled, “A Construction Industry Blueprint: Suicide Prevention in the Workplace.” The guide is a clear call to action for construction executives around the world to make suicide prevention a health and safety priority. It also gives managers some solid guidelines on healthy approaches and prevention measures.

Modeled around Australia’s “MATES in Construction” program, which has dramatically reduced industry deaths by suicide, the guidebook is helping contractors communicate the importance of mental health to managers, supervisors and employees. Key elements include training on how to have difficult conversations as well as examples of positive, health-oriented messages. “The key is to communicate that mental health challenges happen here, and if you or someone in your family has an issue, we have resources to help,” Spencer-Thomas says.

RK puts posters on jobsites that are aimed at reducing the stigma surrounding mental health, and the company newsletter features a relevant article each week to encourage discussion of the subject. RK’s wellness program includes a coach trained in suicide awareness and prevention.

Kinning speaks about mental health at weekly jobsite barbecues and says that, so far, the firm has been able to step in and get assistance for employees at risk for suicide on at least three occasions. In one situation, an employee called him directly; in another case, an HR person brought it to his attention. “We’re elevating the conversation around mental health and getting people to talk about it,” he says.

“It takes a special, courageous leader to speak out about their own life challenges or those of a loved one,” Spencer-Thomas says. “When a leader steps forward and says that it touches all of us, and this is what I did to get better and take care of myself, it makes it OK, and people feel they are supported. It’s a tough thing for leaders to do, but they are seen as even more credible and powerful for being so genuine.”

The Construction Financial Management Association, Princeton, N.J., has been a conduit for Beyer’s passion, says Stuart Binstock, CFMA president and CEO. “It’s what we’re in the business of doing: educating our members about construction industry issues. This is as important a topic as we could cover on the human resources front; it’s a key component of a firm’s financial resources.”

CFMA’s largest chapter, Valley of the Sun in Phoenix, is holding a regional suicide prevention summit in April that, if successful, will be replicated across the country. “This is not just a mental health problem. This is about blanketing vulnerable populations with a safety net,” Beyer says. “I won’t be happy until we have a tsunami of compassion to take care of our people.”