For Anthony Jones, 46, a Gulf War veteran and apprentice craftworker based in Flint, the work that he does—pulling out lead service lines to homes—is personal. After news reports surfaced that drinking water in the Michigan city contained high amounts of lead, he had his children tested. All had elevated levels of the substance in their bloodstreams. He says that knowledge keeps him up at night.

Public health officials say no level of lead exposure in children is safe and that children exposed to lead can experience learning and developmental difficulties years after exposure.

Jones was working at a bottled-water distribution center when he was recruited to participate in an apprenticeship-readiness program to replace lead service lines and work other area construction jobs. After going through the four-week training program, he initially worked on the construction of a new water treatment plant in Genesee County. Now, he is working for one of three construction firms digging out the corroded lead lines scattered throughout the city.

Article Index:

“A lot of people have left Flint,” Jones says. “But I wanted to stay. I can tell my grandchildren that I [was] part of the solution” to the crisis.

In early October, one year after the revelations about Flint’s lead-tainted drinking water burst into public awareness, there are signs that the beleaguered city is slowly waking up from its long water quality nightmare.

Construction crews are in residential neighborhoods, knocking on doors and pulling out old lead service lines. The mayor, Karen Weaver (D), is pushing Gov. Rick Snyder (R), the state Legislature and Congress to provide more funding to remove and replace those lines and, later, revamp the city’s water and transportation infrastructure. Last month, Congress passed an aid package for the city that supporters hope will reach the president’s desk before the end of the year.

But critics say the lead service-line work is moving at a glacial pace—only about 250 out of the more than 4,000 known lead service lines scattered throughout the city have been replaced to date, and the water is still not considered safe to drink. Since the beginning of 2016, at least 10 cases of Legionnaires’ disease have been reported, three of which came in the past month, according to the Genesee County health department.

Cases of Shigellosis, an infectious disease caused by the bacteria Shigella, are on the rise because locals are afraid to bathe or wash their hands in the water, even though federal officials have said the water is safe for bathing as long as lead filters are used.

“Flint is, as we all know, a canary in the coal mine.”

–Flint Mayor Karen Weaver

In many ways, the situation in Flint is unique. A state-appointed emergency manager in 2014 made a unilateral decision to switch the city’s drinking-water supply from Lake Huron, which provides Detroit’s water supply, to the polluted Flint River; then the city failed to ensure that proper corrosion controls were applied to prevent lead from leaching into the water. A few months later, citizens began complaining of vomiting, rashes and hair loss. A U.S. Justice Dept. probe is underway, and criminal charges have been filed against multiple parties, including the city’s former water supervisor (ENR 4/25-5/2 p. 16).

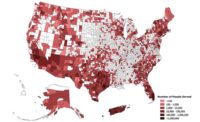

In other ways, Flint is emblematic of a larger problem: Many cities across the country, particularly Rust Belt cities with older networks of drinking-water pipes and service lines, could be facing similar scenarios with not only lead but also other organic contaminants, such as perchlorate—a component of rocket fuel—and Legionella bacteria.

“This is a national issue,” says Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech engineering professor who helped to bring to light the drinking-water lead levels that reached up to 4,000 parts per billion in some Flint homes. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requires remedial action under the lead-and-copper rule when the level reaches 15 ppb.

A Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) report, released in June, found that at least 5,000 water systems across the U.S. violated the lead-and-copper rule in some way in 2015 (ENR 7/11 p. 6). But those are just the utilities with recorded violations. Flint did not have any lead violations under the rule on the books, says Erik Olson, director of NRDC’s health program and one of the report’s authors.

NRDC says EPA took formal enforcement actions on only about 11.2% of the more than 8,000 violations that occurred in 2015. Because EPA seldom penalizes utilities that violate the lead-and-copper rule, some utilities have tended to use flushing techniques and other methods to “game the system” to avoid incurring reportable violations, Olson says.

In February, EPA instructed water utilities that they must comply with the lead-and-copper rule, which will be revised some time in 2017, and gave them detailed guidance on how to comply. Consequently, there could be a spike in systems that find lead in their water supply. “It’s too early to know … but we think that if you did legitimate testing, a lot of systems are going to have problems that didn’t show up before,” Olson says.

Earlier this year, the village of Sebring, Ohio, had its own lead crisis, exacerbated by the failure of the village’s water superintendent, Jim Bates, to report elevated lead levels for months. The superintendent was terminated and now is facing a criminal trial.

But where, at least publicly, EPA’s regional and federal offices seemed slow to respond to Flint’s problems, they were on top of the crisis in Sebring. Olson says the quick response to Sebring’s problems, which have been resolved, is partially a result of “lessons learned from Flint.” He says, “I think that Flint taught a lot of people that what had been acceptable … basically sweeping the problems under the rug … got Flint in trouble and the state [of Michigan] in trouble.”

Doug Owen, principal with Owen Water Consulting in San Diego and former chief technology officer at Arcadis, notes that many public water utilities are doing the right thing and working hard to ensure that drinking-water systems are safe. “People that we work with … people in leadership positions are very focused on this and do their [lead-and-copper rule] reporting.” He says that even well-resourced utilities can run into trouble if they are not careful when switching water sources or adding other types of treatment.

In the nation’s capital, for example, DC Water saw a sharp spike in its lead levels after it switched from chlorine to chloramines in its treatment process in 2001. DC water made the switch to improve water quality because chlorine was known to generate chemical by-products during the treatment process. “What was unknown at the time is that chloramines caused the scaling that formed a protective layer inside the pipes to be reduced and allowed lead to leach” into the water supply, says DC Water’s CEO and General Manager George Hawkins. “No one knew that the chemistry change was going to have this consequence.”

To fix the problem, the utility has added orthophosphate to coat the pipes, which is now a generally accepted corrosion-control method.

Tom Hickmann, director of engineering and infrastructure planning for the city of Bend, Ore., and co-chair of the American Public Works Association’s Water Resources Committee, observes, “Engineers need to be incredibly sensitive to the chemical composition of the water supply so that they are making sure they are not exacerbating the problem.”

Lead Replacements Start Slowly

Meanwhile, Flint’s ironically named Fast Start program has been slow to take off, due to a lack of funding. “They’re trying to get the projects out, but the money’s not coming in fast enough to expedite the process,” says Howard Hipes, an apprentice and training coordinator in Flint. Hipes says he has apprentices able and ready to work.

Retired Brig. Gen. Michael C.H. McDaniel, brought on by the city to manage the program, says prices have come down, but it still costs approximately $6,000 per home to replace the pipes. “It’s still higher than we want it, so we are calling this [current] phase a pilot to see if we can get the costs down by concentrating on a couple of companies, giving them a set amount of work and visiting them on a daily basis,” he says.

The city estimates that there are at least 4,000 known lead service lines in Flint, based on city records and a study performed by Rowe Engineering. However, for another 13,000 service lines, the city can’t say for sure whether they are lead, galvanized steel or copper, but history indicates that many of those are likely to be made of lead. Ryan Doyle, a state engineer on loan to the city from the Michigan Dept. of Transportation, says, “Right now, we are finding there is probably a lot more lead out there than we thought.”

Some sources have criticized the city’s records and maps. “The maps mean nothing,” says Harold Harrington, business manager for Local 304 of the United Association, the plumbers’ union. “They have to go up the valve box and check at each side of the valve box in the yard” to determine whether pipes are copper, lead or galvanized steel.

The city recently hired contractors to use hydrovac equipment to carve out 1-ft holes in properties to be able to determine the composition of some of the pipes, says Doyle. City records have been fairly accurate in showing where the copper pipes are, he adds.

Thirty-three homes had their pipes replaced in a pilot phase; since then, the work has been divided into three contracts, all to local firms: Goyette Mechanical, W.T. Stevens Construction, and Johnson and Wood. Goyette, which submitted the low bid, is doing partial replacements—generally up to the curbside in 100 of the homes in areas in which maps and records indicate that the pipes running into the homes are made of copper; the other two firms, doing 50 homes each, are doing full service line replacements.

The city was reviewing bids on the next 300 homes at press time and could have the next phase, funded with $25 million from the state Legislature by mid-October, completed by Thanksgiving, Doyle says.

Partial line replacements, although once routine, are now generally thought to be ineffective and can actually make things worse if the dwelling contains lead pipes, rather than copper, inside the home, says DC Water’s Hawkins. “By digging holes and replacing the pipe, you rattle the system, and that can increase a short-term elevation of lead in the water, which is just the opposite intent,” he notes.

Flint’s mayor initially had called for the line replacements to be performed by digging two holes and pulling the pipe out, a faster and more efficient technique. But that method has proven more challenging for Flint than originally thought, says Harrington. “If they can pull it, they pull it. But a lot of these pipes … go under roads, and the dirt is so compacted, you can’t pull it.” Tree roots, sewer lines and other debris can kink the pipes, too, which makes them difficult to extract.

As a result, the construction crews more often are using directional boring, or open excavation, to remove the pipes. “I think it’s more about getting it done than what method they are using, so we’ve been letting them use whatever method they think they can use to get it done at decent prices,” Doyle says.

Looking Ahead

The lead-service-line replacement work is expected to take at least a few years. Meanwhile, extensive water sampling, conducted by Virginia Tech’s Edwards, EPA and state officials, have shown that lead levels have been going down since the city switched its water source from the Flint River to Detroit’s supply, Lake Huron. “The day is coming when it might be safe to drink the water again, but not yet,” says Edwards.

Bringing water from Lake Huron, a new $285-million pipeline, built by the Karengoldi Water Authority in Genesee County, eventually will supply water to Flint’s treatment plant. However, EPA wants a new $7.2-million, 5.5-mile pipeline to be built parallel to the KWA line to be able to test the water extensively before the switch is made.

The city also has ambitious goals to right-size its water and transportation infrastructure to meet the current population’s needs, says Natalie Pruett, an independent planning consultant for the city.

The mayor released the plan in August. The cost of the underground water-infrastructure portion of the program could range from $716 million to $1.807 billion, depending on which technologies and methods are used. The work would include replacing and reinforcing water mains, replacing and reinforcing service lines, disconnecting vacant properties from the water delivery system and integrating vacant lots into the storm-management system.

The city currently is raising funds and hopes to put out an RFP to find a firm that could develop a comprehensive engineering plan as soon as possible, Pruett says.

Funding Boost

Funding is always an issue for a place such as Flint, which, like many other post-industrial cities, has seen its population dwindle over the past decades and, consequently, its tax base.

But relief may be in sight. After months of delays, Congress finally seems to have blessed an aid package to Flint. The Senate-passed Water Resources and Development Act includes $220 million for Flint and other cities where the president has issued a public health or other emergency declaration. The House-passed bill includes a smaller package, only $190 million, but Tommy Holmes, legislative director at the American Water Works Association, says he believes the final number will be closer to the Senate’s total than the House’s as conference negotiators reconcile the two bills during the lame-duck session.

Mayor Weaver has been advocating for more federal funding for months. “Flint, as we all know, is the canary in the coal mine,” she said at an Aug. 4 community address. “If Flint is forgotten and left to suffer alone after a decade of neglect and a man-made disaster, it will be a sad reflection of the challenges facing our entire nation and its people. …No other city, no other people, should have to go through what Flint and its residents have had to endure.”

By Pam Hunter McFarland, with Mike Anderson