Benchmarking Rules Show Promise for Reducing Building Energy Use

Nineteen U.S. local jurisdictions and two states have enacted energy-use disclosure laws since 2008

Pittsburgh and Portland, Maine, are the most recent local jurisdictions to enact building energy benchmarking laws. Map Courtesy of the Institute for Market Transformation

Pittsburgh, and Portland, Maine, recently enacted building energy-use benchmarking laws—making the number of local U.S. jurisdictions that require some form of annual reporting of building energy use total 19. Though data is just beginning to trickle in, recent studies indicate that the disclosure policies themselves may be spurring energy conservation in public and private buildings.

“A lot of U.S. cities are taking a leadership role, responding to the threats of climate change and making commitments to reduce carbon emissions,” says Zachary Hart, manager of building performance policy at the Institute for Market Transformation, a nonprofit devoted to cutting building energy consumption. “Energy benchmarking is one piece of the pie,” he adds.

Benchmarking is the process of measuring building energy performance—typically, through utility bills—and comparing that against consumption patterns of similar buildings, using the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Energy Star Portfolio Manager tool. Energy Star is a joint EPA-U.S. Dept. of Energy (DOE) program that encourages the energy-efficiency improvement of a wide range of consumer and commercial products, enhancing energy efficiency in buildings and promoting energy management planning for businesses and other organizations. The energy performance of buildings can be rated on the EPA’s Energy Star 1-100 energy performance scale relative to similar buildings nationwide.

Disclosing Energy Use

Benchmarking policies require building owners to gather and disclose their energy use, sometimes on a public website, which is intended to lead to a virtuous cycle: Injecting the information into the market makes it possible for potential buyers, renters and tenants to see which buildings are more energy efficient, and thus to consider this quality in their purchase or leasing decisions, says the 2016 ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings.

Benchmarking-rule specifics, including which buildings are covered, vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. But all benchmarking rules, including Pittsburgh’s Energy Benchmarking and Transparency Ordinance that went into effect in October, establish baselines for energy use that allow comparisons of buildings and enable cities to create management tools to use resources more efficiently.

The Pittsburgh ordinance, which is part of the city’s plan to slash in half city-owned and commercial building energy use by 2030, “can benefit both the public and private sectors by allowing us to understand consumption patterns and resource allocation,” says Grant Ervin, chief resilience officer in Pittsburgh’s office of sustainability.

That gives owners additional incentives to invest in energy efficiency. For the private sector, there is the opportunity to create real estate value and get a “huge return on investment” for capital improvements, adds Ervin.

Positive Impacts

Washington, D.C.'s pioneering benchmarking ordinance only went into effect in 2008, so it is still too soon to tell whether benchmarking policies themselves are contributing to long-term energy conservation. Some early studies suggest there have been some positive impacts, especially in New York City, which enacted its benchmarking Local Law 84 (LL84) in 2009. “The total disclosure policy can be credited with a 6% reduction in building energy-use intensity three years later and a 14% reduction in EUI four years later. The disclosure of Energy Star scores decreased building EUI by 9% three years later and 13% four years later,” according to “Measuring Energy Savings From Benchmarking Policies in New York City” by researchers Ting Meng and David Hsu at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Albert Han at the University of Pennsylvania.

A May 2015 “New York City Benchmarking and Transparency Policy Impact Evaluation Report,” prepared for DOE by Navigant Consulting Inc., Steven Winter Associates Inc. and Newport Partners LLC, concluded there was a cumulative energy savings of 5.7% during the first four years of the policy, from 2010-13. The reduced energy use cut utility bills by nearly $267.5 million.

In August 2016, the National Electrical Manufacturers Association published the results of a survey of New York City facilities managers. The survey found that, because of LL 84, 77% had made changes in how they operate their buildings and 75% had installed new energy-efficient equipment.

In 17 cities with benchmarking rules, the rules apply to both commercial and public buildings. In 12 cities, the rules apply to multifamily buildings, as well. In Denver and Salt Lake City, the rules apply to only public buildings.

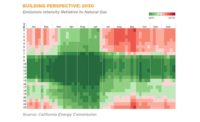

Beyond Washington, D.C., benchmarking-rule pioneers are Austin and New York City, which enacted laws in 2009. Other cities with rules are Seattle; San Francisco; Atlanta; Philadelphia; Boston; Chicago; Minneapolis; Boulder, Colo.; Portland, Ore.; Berkeley, Calif.; Cambridge, Mass.; and Kansas City, Mo. Washington state and California also have rules.

One recent report, “Does Information Provision Shrink the Energy-Efficiency Gap? A Cross-City Comparison of Commercial Building Benchmarking and Disclosure Laws,” looked at Austin, New York City, San Francisco and Seattle. It found that the laws reduced utility expenditures by about 3% in evaluated office buildings.

To create rules and implement benchmarking programs, cities “have organized themselves to share information and best practices,” says Hart. “We’re creating a template of policies and programs,” based on lessons learned from other cities, adds Ervin.

It took Pittsburgh two years to develop and enact its benchmarking law. But since its sustainability program started in 2014, energy consumption has dropped 10% in city-owned buildings, he says.

“Once you start looking at consumption and data analytics behind it, you understand how much we waste” and how inefficient the building systems are, Ervin says. “We’re starting to put all the puzzle pieces together.”

Editor's Note: On Dec. 12, Evanston, Ill., became the 20th U.S. jurisdiction to adopt a benchmarking ordinance.