Few industries are as fluid as construction when it comes to teaming up with other companies. But what happens when companies sign a teaming agreement and help land a big project, only to get kicked off the team? Can they sue?

A federal court’s new ruling finds that they can sue due to the legally enforceable teaming agreement’s promise to negotiate. The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia in early June ruled against a motion to dismiss by contractor Amec Foster Wheeler. It was battling a claim brought by a subcontracting team of Delmar, Del.-based Crystal Steel Fabricators and Culpeper, Va.-based Memco Inc. after the companies failed to win work helping to build a part of the Aegis Ashore Missile Defense System on the Redzikowo Base in Poland. The project cost was $183 million.

Amec violated a teaming agreement when it went with another sub after landing the work to build the new missile defense complex, the subcontractors contend. The project involves building launcher foundations, apron and crane pads, power-plant facilities, warehouses and affiliated site structures.

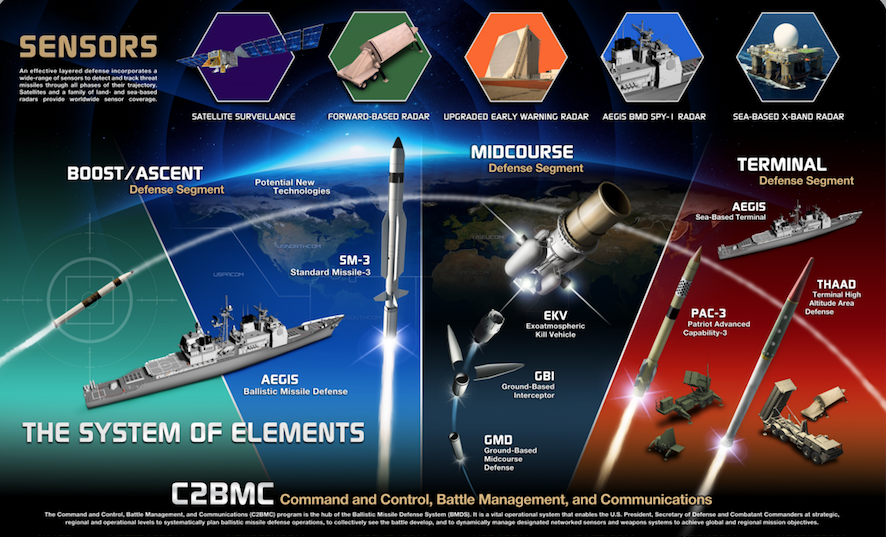

|

| The type of land-based missile defense structure involved in the teaming dispute lawsuit. |

Crystal Steel and Memco contend they spent $150,000 on price proposals and other materials related to Amec’s successful bid to win the project, which was awarded by the U.S. Army Corps. of Engineers in 2016.

Firing back, Amec argued the teaming agreement was legally unenforceable in Georgia—calling it an “agreement to agree”—and filed a counterclaim against Crystal Steel for its legal expenses and other damages. In its response to the claims of its spurned subcontractor, Amec points to the teaming agreement signed by both companies, which states, “This Agreement does not represent a guarantee of work to Subcontractor.” It gave few clues about why it didn’t give the job to the Crystal Steel-Memco team.

However, the court argued that while the teaming agreement inked by both firms did not include a guarantee of work, it did include a promise to negotiate in good faith, which can be enforced in court.

“There is ample support for enforcing contracts to negotiate—authority that the Georgia Supreme Court would likely find persuasive,” U.S. District Court Judge Mark H. Cohen wrote. “The case appears to involve an up-front investment of time and resources that might lead parties to enter into a contract to negotiate,” Cohen notes.