The American Infrastructure

Above, Below and Through: How They Build L.A.'s New Light Rail Line

The project has a little bit of everything when it comes to heavy construction

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

RENDERING COURTESY OF HNTB

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Crenshaw Boulevard will be transformed not only into a light-rail corridor but also into a more pedestrian-friendly development hub.

PHOTO COURTESY OF METRO

Standing on the patio of Dulan’s, a soul-food restaurant that has served the Crenshaw neighborhood of Los Angeles for a quarter-century, owner Gregory Dulan gestured at the unfinished rail alignment stretching along the length of Crenshaw Boulevard just yards away. In anticipation of the line’s 2019 completion, he described the renovation and expansion plans of his restaurant.

“We’re along for the ride,” he said.

The 8.5-mile, $2.1-billion light-rail line will be a new major artery in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) transit system. It will link directly to two other lines—the Exposition Line and the Green Line, outside of Union Station downtown—and provide access options to the historic cultural neighborhood of Leimert Park, the future L.A. Rams stadium, downtown Inglewood, a planned museum and local businesses such as Dulan’s.

The Crenshaw-LAX Transit Project is one of 28 projects prioritized by Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti (D) for completion before the 2028 Olympics. It is also one of the projects funded by a 2008 voter-passed half-cent sales-tax increase.

Building the line requires going above, below and through the busy Crenshaw corridor and will include a pair of mile-long bored tunnels, two miles of cut-and-cover tunnels, a new bridge soaring above Interstate 405 and a delicate thread through existing highway structures, linking up with the Green Line at Los Angeles International Airport. The double-tracked alignment includes eight stations, six bridges, park-and-ride facilities at three locations, utilities, landscaping, local road improvements, and a maintenance and storage facility.

“This project is a cornucopia of heavy-civil work.”

– Rick Felkins, WSCC Senior Project Manager

“This project is a cornucopia of heavy-civil work,” says Rick Felkins, a senior project manager with Walsh/Shea Corridor Constructors, the design-build team that holds the $1.3-billion contract to build the line. Noting the extensive falsework and support systems required for both bridges and cut-and-cover tunnels, he says, “Even the temporary engineering was massive in and of itself.”

HNTB and Arup began design in 2013, with 250 people at peak. “Many parts of the project could be an entire project within themselves,” says Christopher Devery, HNTB design manager. During design, the airport announced plans to build an automated people-mover system, which impacted the alignment of the Crenshaw line. “We made adjustments in short order to accommodate the future 96th Street-station connection,” says Devery. Designers adjusted 2,000 ft of track alignment, he says.

Under and Over

Excavation included 160,000 cu yd from tunnel boring, 385,000 cu yd of underground stations and 325,000 cu yd from cut-and-cover work.

Named for the abolitionist Harriet Tubman in local schools’ naming contest, “Harriet,” a 21.5-ft-dia tunnel-boring machine, began excavating southbound, 70 ft deep through silts and sands, in April 2016. The earth-pressure-balanced TBM, built by Herrenknecht, completed the first mile-long tunnel in October, averaging 60 ft a day. Then, crews took the 950-ton, 400-ft-long TBM apart, trucked it back to the station that will connect to the Expo Line, reassembled it and began digging the second tunnel in November. That tunnel was completed in April 2017.

The tunnels include five cross-passages at approximately 750-ft intervals that are jet-grouted due to the alluvium sands, clays and cobbles, says Matt Gallagher, director of construction management for Metro.

Temporary shoring work required tremendous engineering efforts, he says.

– Jeff Mays, WSCC Senior Project Manager

Tunneling went smoothly, with no major issues of settlement, groundwater or methane emissions, say project officials. Archeological issues have been minimal, as well: During station excavation last year, crews uncovered ancient bison and sloth bones about 16 ft deep, notes Gallagher. Ranging in widths from 66 ft to 125 ft, underground-station boxes are about 400 ft long—except for the Expo station, which is 800 ft to allow for crossover tracks, notes Charles Beauvoir, Metro project director. Temporary shoring for the Expo and MLK stations used cutter soil mixing, rather than beam and lagging, due to water-contamination concerns.

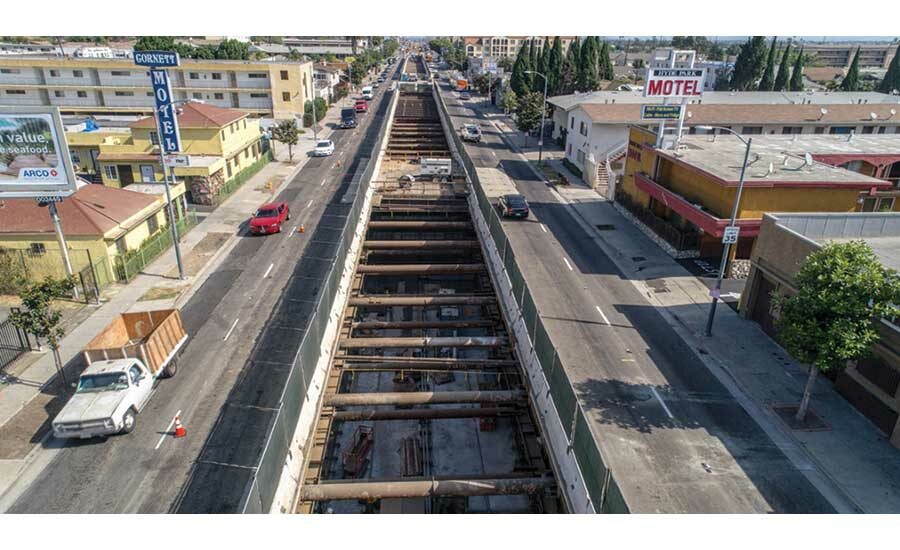

A mile’s worth of cut-and-cover construction in the median of Crenshaw Boulevard includes steel soldier piles and steel beams that support concrete decking for traffic. The temporary shoring work required a “tremendous” engineering effort, says Jeff Mays, WSCC senior project manager. “We installed over a thousand 70-ft-long soldier piles with businesses just 15 ft away.” The cantilevered decking system allowed crews to maintain two lanes of boulevard traffic while excavating top-down. “We were able to excavate most of the structure from the top, as opposed to hauling everything up from the bottom,” he says.

Crews also used two specialized EFCO tunnel-traveler formwork systems to pour 50-ft sections at a time in a three-day cycle. The expandable system allowed crews to pour the concrete for both the walls and the roof of the tunnel at the same time, doubling production time, Mays says.

Last May, crews completed a 1,510-cu-yd, 21-hour pour for a 315-ft-long main span of an overpass that will carry the Crenshaw rail line over the congested I-405 freeway. A 720-cu-yd, 12-hour pour followed. The design-build team revised the original plan, which would have required a new column in the median of the freeway. The cast-in-place box-girder bridge with parabolic flares “cribbed off” an existing freight-rail bridge, rather than demolishing it, says Felkins. The old bridge was sturdy enough to support falsework for the new one.

The pour included a complex web of pipes that pumped chilled water to cool the concrete. Supported on 11-ft-dia piers as deep as 170 ft, two columns straddling I-405 will accommodate the future widening of the freeway.

In that segment, WSCC employed deep soil mixing for mechanically stabilized earth walls to protect a 66-in.-dia, 100-year-old sewer line, which runs adjacent to the alignment; and, farther west, lightweight concrete for MSE walls to protect a 13,400-kV power line that feeds the airport.

Labor and staffing is a challenge considering the amount of L.A.-based construction occurring, he says.

– Charles Beauvoir, Metro Project Director

The team also changed the previous at-grade alignment near the airport to 2,600 ft of cut-and-cover tunnel. “The FAA was concerned about the trains being near the runways and causing pilot distraction,” says Beauvoir. “They asked us to depress it.” Crews used a vibratory pile system to install 700 piles during hours when the airfield was shut down. Crews also installed two 500-ft lids with the capacity to handle planes if they overrun the runway, adds Kimberly Ong, deputy executive officer with Metro.

In that section, crews on Jan. 26 shut down five Green Line stations to connect the Crenshaw and Green lines. The effort is expected to take about two months. Ong notes that the alignment passes below the 105 Freeway overpass with 15-ft minimum clearance and just above the Imperial Highway bridge. “We call it ‘threading the needle,’ ” she says.

The Crenshaw-LAX project also includes a $307-million, 18-acre Southwestern Yard maintenance facility for both the Green Line and Crenshaw Line trains. A joint venture of Hensel Phelps and Herzog, working under a $172-million contract, is scheduled to complete the yard this year.

Streetwise

The at-grade sections of the job required extensive coordination with multiple city agencies and businesses to minimize impact, says Mays. Other local challenges include the sheer amount of construction projects, including Metro’s Purple Line and the new Rams stadium, notes Beauvoir, adding, “It creates a big staffing challenge.”

Under its project labor agreement with WSCC, Metro is the first transit agency in the nation to adopt a “local hire” pilot program under an agreement with federal agencies. It includes a requirement that project hours be worked by 40% locally targeted workers, 10% by disadvantaged L.A. residents and 20% by apprentices.

“This is going to turn the arterial into a true multimodal corridor.”

– Christopher Devery, HNTB project manager

Inspired by previous efforts in Houston, Metro also implemented a construction-mitigation pilot program for impacted small businesses. It provides up to $50,000 a year to qualified applicants; so far, Metro has paid out $6 million, says Jose Ubaldo, Metro spokesman. Metro also inaugurated two other pilot projects: a free business training and consultation service and an “eat, shop, play” campaign, wherein Metro promotes patronage of local businesses, says Ong.

In terms of context-sensitive design, the at-grade stations are among the first to use Metro’s new kit of standards for design elements, says Devery. “It is intended to bring an overall theme and consistency to Metro’s stations,” he says. “The feel of the stations is standardized in terms of the canopies, surrounding glass, the layout of the ticket vending machines, the kiosks and signage.” Local artists will be commissioned to display their work at entrances and on platforms.

“This is going to turn the arterial into a true multimodal corridor,” says Devery, noting that cars and buses will still traverse Crenshaw Boulevard on either side of the light-rail tracks. “There will be larger sidewalks. The street and landscaping improvements are going to be beautiful. In the end, it’s going to be an asset to existing businesses and future development.”