Superfund Push Yields Few Results

Cleanup continues at the GE-Pittsfield/ Housatonic River Superfund site in Massachusetts (above) and at the San Jacinto site in Houston.

PHOTO COURTESY ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS

Cleanup continues at the GE-Pittsfield/ Housatonic River Superfund site in Massachusetts (previous photo) and at the San Jacinto site in Houston.

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY (BOTTOM)

Speeding up the notoriously slow-moving Superfund program appears to be a priority for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt as he looks to revamp the entire agency.

He has taken direct control of the hazardous-waste cleanup program’s largest sites, created a task force to address its problems and recently identified 21 sites for “immediate, intense action.”

EPA proposed plans on Feb. 1 to clean up legacy nuclear and chemical waste dating to the World War II-era Manhattan Project that was illegally dumped at the West Lake Landfill in Bridgeton, Mo., in the 1970s. In January, the EPA said it reached a preliminary pact with key parties to address cleanup work at the Silver Bow Creek Butte Area Superfund site in Butte, Mont. In October, the agency OK’d a $115-million cleanup at the San Jacinto Waste Pits site, near Houston. “There is nothing more core to the agency’s mission than revitalizing contaminated land,” Pruitt said last year.

But those familiar with the program say it is not clear whether Pruitt will have an impact on an underfunded program in an agency that doesn’t yet have in place all its regional administrators.

“It’s probably too early to tell” the impact of Pruitt’s actions, says Alan Elia, CEO of Sevenson Environmental Services, a longtime Superfund contractor. He says it takes years to craft a site remediation design, and potential changes have not flowed through to firms such as his.

There is a lot of buzz around the Superfund program, says Elgie Holstein, Environmental Defense Fund director for strategic planning. According to Holstein, a key indication of Pruitt’s effectiveness will be the Trump administration’s next annual budget request, set to be released on Feb. 12. This year’s budget proposed cutting the program for this fiscal year by 30%, to $762 million from $1.1 billion. “You certainly can’t accelerate cleanup while protecting human health and the environment on a reduced budget,” he says.

Long-Term Slowdown

But Pruitt’s effort to jump-start Superfund cleanup comes amid a long-term slowdown in the program.

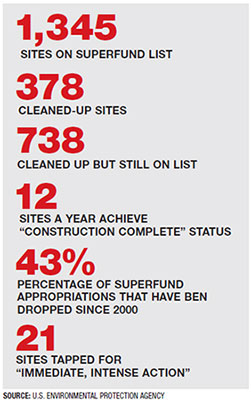

There are roughly 1,345 waste sites on Superfund’s National Priorities List (NPL), which indicates they may need cleanup action. So far, 378 non-federal sites have been cleaned up and taken off that list, and another 738 non-federal sites have had all cleanup measures put in place—that is, achieved “construction complete” status—but still have not been removed from the list, according to EPA.

From 2000 to 2012, 27 non-federal sites per year achieved construction-complete status, according to a report released in June by the American Council of Engineering Cos. (ACEC). Since 2012, the average number of construction-complete sites fell to 12 sites per year, says Katherine Probst, a Superfund consultant who wrote the report. At the same time, since 2012, the pace of sites removed annually from the NPL has dipped to eight.

From 2000 to 2012, 27 non-federal sites per year achieved construction-complete status, according to a report released in June by the American Council of Engineering Cos. (ACEC). Since 2012, the average number of construction-complete sites fell to 12 sites per year, says Katherine Probst, a Superfund consultant who wrote the report. At the same time, since 2012, the pace of sites removed annually from the NPL has dipped to eight.

Meanwhile, Superfund appropriations have dropped 43%, to $1.1 billion in 2016 from $1.9 billion in 2000, according to the report.

When possible, the EPA requires responsible parties, such as site owners, to pay for site cleanup, a process the agency manages and oversees. A lack of funding has forced the agency to delay cleanup action at some sites in 14 of the past 17 years, according to the ACEC report. Further, the underfunding likely has prevented sites from being added to the priority list and caused site studies and remedial actions to be spread out over a longer period.

Holstein doubts that efforts to make the Superfund program more efficient, including the EPA’s new “lean management initiative” that is being implemented across the agency, will reduce the amount of money needed for the program. The management system, developed by Toyota, aims to create “more effective ways to better serve EPA’s customers while freeing up the capacity of EPA employees to do more environmental good,” the agency says on its website.

Such an approach, which calls for treating industry as the “customer,” likely would lead to poor results in the Superfund program, Holstein says.

Pruitt has taken several steps that he contends will improve the Superfund program. In May, he took authority from EPA’s assistant administrator for the Office of Land and Emergency Management and from regional administrators to make decisions on Superfund cleanup remedies that cost more than $50 million and directed regions to coordinate more closely on those sites with his office.

In July, an EPA task force issued a set of 42 recommendations that included creating a list of sites that were ready for “immediate, intense action” and identifying sites that are good candidates to be redeveloped. In December, EPA released a list of 21 sites ready for “immediate” action; one month later, it issued an inventory of 31 sites that are ideal for redevelopment.

In response to the task force’s plan, Pruitt directed the agency to increase the use of early and interim actions to respond to immediate risks and make parts of a site available for reuse. The EPA is still studying the directive, according to a Feb. 1 report that outlines how the agency is responding to the task force’s recommendations.

No Obvious Changes

Despite Pruitt’s comments, his directives have not seemed to trickle down to those who have to implement them. “I haven’t seen changes in directions and improvements,” says David Rosenblatt, managing partner at Boston law firm Burns Levinson, who represents alleged polluters and buyers of contaminated properties. “I haven’t seen any reforms.”

The task force’s recommendations provide only a blueprint for reform, Rosenblatt says, noting that EPA’s Boston-based region, where his work is focused, has no regional administrator in place yet to implement Pruitt’s vision.

Probst is monitoring whether EPA steps up use of “removal actions,” which are short-term measures that address immediate risks. She says such a move would be a concern if the agency were to use removal actions to avoid long-term cleanup.

She also is skeptical of the push to redevelop Superfund sites. Site reuse is not a new concept, although creating a redevelopment list indicates that it is a higher priority for Pruitt than it may have been at the agency before, she points out.

State environmental regulators have not seen substantial changes, either, according to Ken Kloo, president of the Association of State and Territorial Solid Waste Management Officials and director of the division of remediation management at the New Jersey Dept. of Environmental Protection.

From a state perspective, New Jersey continues to have an excellent working relationship with region-based EPA Superfund managers but has not seen any significant changes under the Trump administration, Kloo says. However, the state waste managers’ group has been invited to work with the task force to create recommendations, he adds.

But it remains unclear if any task-force recommendations have taken effect because of a lack of transparency at EPA, according to ACEC report author Probst. “It’s very hard to tell if they are making changes to speed up Superfund,” she says. “I basically don’t have a clue.”