1Q Tech Report

Making Construction Innovation Stick

A HoloLens view of contours of floor flatness is overlain with metrics from laser scans. “Augmented reality makes the difference, especially to those that need to do the work,” says Tomislav Žigo, vice president for VDC at Clayco.

IMAGE COURTESY OF CLAYCO

Clark Patterson Lee’s network of technology-savvy employees at CPL Creative Labs taps skills in its 13 offices for support, training and production to create tools like this virtual walk-through of an unbuilt design.

IMAGE COURTESY OF CPL

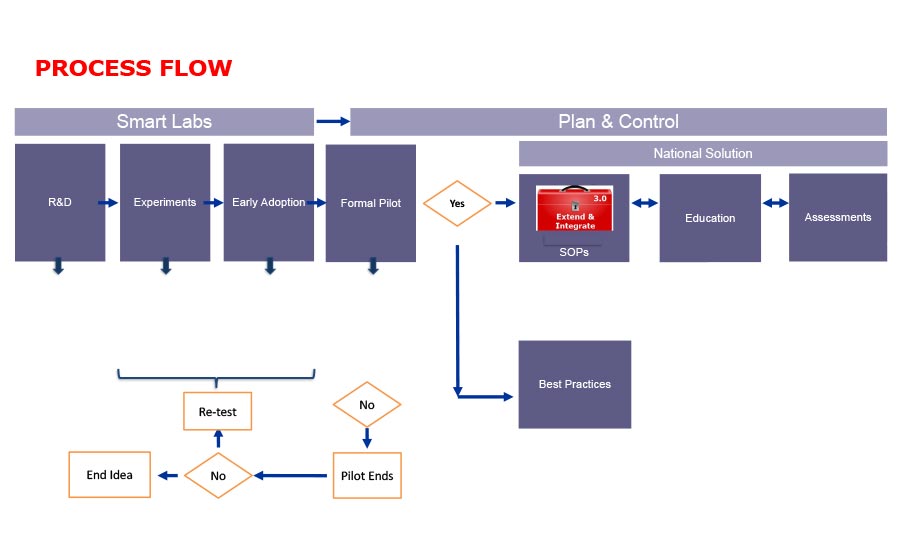

Suffolk Construction follows a flowchart for developing and testing new ideas before they become a part of the firm's SOP toolbox.

Image Courtesy of Suffolk Construction

WeWork’s acquisition of social-media inspired FieldLens for enterprise-wide project management puts technology, such as reality-capture- based planning and project execution, first.

IMAGE COURTESY OF WEWORK

Integrating innovations into construction workflows—rather than serially testing, piloting and discarding them—is a definition of success. Yet few innovations—even ones that shine in trials—are absorbed into practice. Many just quietly go away, sending the work of vetting and testing them down the drain. That leaves some firms wondering if most construction technology innovation efforts are a waste of time.

But instead of giving up, those frustrations lead others to step back and improve innovation processes. They are finding ways to make sure they not only focus on the most beneficial innovations, but also on ones that will be put to wide use on multiple projects. Their strategies for winning the technology-innovation game can be described either as top down, regionally driven with national support, individually championed or philosophically grounded and based on production and safety fundamentals.

One approach is to select and hard-wire innovative technology right into the corporate backbone for enterprise-wide deployment. WeWork’s acquisition of and standardization on FieldLens last June as its construction-documentation and process-management platform across all its real estate development operations is an example.

Tim Dumatrait, WeWork’s head of construction, says the company, which builds out and manages office facilities for its 200,000 “members” in 66 cities across 20 countries, ran an aggressive testing program to search for the right tool to coordinate its real estate acquisitions, design, construction and operating teams before it settled on FieldLens. “It was a year before we started narrowing it down,” Dumatrait says. “We settled on FieldLens because it was the most flexible. All of the other tools were too highly specialized.”

“This is the most forward-thinking real estate company in the world, and tech is at the center of what we do.”

– Douglas Chambers, Vice President of Powered by We

Douglas Chambers, co-founder and CEO of FieldLens until the sale and now a vice president at WeWork subsidiary Powered by We, says implementing the system at an enterprise level is a natural for WeWork. “This is a technology company,” he says, describing how an organization that commissions 1 million sq ft of office space a month could hardly be anything else if it is going to stay in front of the management process. He says since so much of its work involves retrofitting existing spaces, reality capture is a big focus. “Inherently, this organization just invents technology in a way that’s not typical. This is the most forward-thinking real estate company in the world, and tech is at the center of what we do,” Chambers says.

The organization has a stable network of consultants and contractors, but all collaborate on the FieldLens platform. And even though FieldLens is an internal tool, it still is publicly available, with all the improvements engineered since the acquisition, Chambers says. “The FieldLens team is thriving here. The interaction they get to have with the builders and designers they work with is really powerful.”

Other firms seeking to incorporate innovations create teams that support new technology experimentation, evaluation, testing and deployment. This encourages evolutionary developments that can prove innovation efficacy in regional operations first, and then support their spread from office to office.

Rochester, N.Y.-based architectural and engineering firm Clark Patterson Lee has established its in-house CPL Creative Labs. It is a virtual group from the firm’s 13 East Coast offices that meets regularly and is “dedicated to staying ahead of all things tech,” says Vince Press, CPL communications director.

The team members’ backgrounds include architects, engineers, marketers and interior and graphic designers. They research, develop and help other employees implement technologies, such as virtual and augmented reality, 360º photography, 3D scanning and printing, and video production.

“The formation and support of the group shows a commitment from our leadership as well as how [innovation’s] importance has permeated the culture and is valued,” says Danny Jones, an architect and a member of the Creative Labs.

“There are quite a few product solutions we deal with,” adds Jones. “Having a deep understanding of how they operate and what they can produce allows us to strategize and determine the best course of action.”

The firm is using 3D modeling and virtual reality as presentation and design validation tools. On the document-production side, Jones says it has “an assembly line, and we are trying to design our efficiencies into that. The more efficient we can be, the better off the project is as a whole.”

One initiative is to make software training available across the company. “We make a video recording of the software itself, with a sound overlay, so we don’t have to travel to every office,” says Jones.

The dedicated resources appear to be helping. Jones says virtual reality is becoming “a way of life” at CPL. He notes that when its new Atlanta office opens this spring, it will have a designated testing, development and demo media lab, with room for future VR pods. “It’s really exciting because it’s changing the culture of design and the way we work as a company.”

Currently, CPL is beta testing both Enscape and 3D Studio Max Interactive, a tie-in to Autodesk Revit. CPL is implementing the tools and VR headsets in a design and planning mash-up to let contractors and owners take virtual walk-throughs before construction begins.

“Enscape is being handled in our Charlotte office, while 3ds Max Interactive is coming from Atlanta. It’s more of an Enscape first, 3ds Max Interactive if needed, approach. A lot of what we’re doing is targeting specific applications and using them for what they’re best at, instead of being tied to a single piece of software and trying to pound the round peg through the square hole,” Jones says.

“One of the great things about Clark Patterson Lee is that we’re a collection of small offices, like incubators. This gives us avenues to experiment. We can change the way 20 or 30 people do things, rather than the whole company at once,” says Jones.

Suffolk Construction has a similar but more structured approach. It is building and staffing “Smart Labs” to collect ideas and support innovation in its offices across the country. But collecting ideas is just the first step in a rigorous evaluation process, says Chris Mayer, executive vice president and chief innovation officer. “We’re focused first on the value proposition,” he says.

For Mayer, the best way to get an innovation to stick is to look for early returns and constantly evaluate it. “We are looking to standardize our process,” he says. “If it shows promise, you move into experiments. There’s a template: What are your key milestones? What’s your expected value? What resources do you need? What assumptions are you making?”

Mayer says the experiment phase typically is 90 days, with interim evaluations every month. Ideas that make it through experimentation go into early adoption, where project teams are invited to champion or critic the new technology. “It’s important at every step to be able to say ‘no, this is not working,’ ” notes Mayer.

One technology Suffolk is testing is a site control and workforce data-collection platform from Veriwolf. It uses RFID tags on badges and helmets, facial recognition and a jobsite mesh network to harvest personnel data and pre-populate forms and daily logs. Suffolk is testing it on a residential project in New York City.

While Veriwolf’s focus is on geo-fencing sites and monitoring workers, that’s only in service of data logging, says Veriwolf CEO Robert Samuels. “It comes down to document control, and tracking the workforce is part of [data acquisition] needed for that,” he says. This means setting up wireless mesh relay nodes, entrance controls and other systems to monitor the site.

Suffolk hasn’t decided whether to go with Veriwolf, but Mayer says it is evaluating how it can use the stream of data. “We need to make these experiments visible to the company so skeptics can bring up valid points, things we should be addressing now,” says Mayer. “Veriwolf is not part of the toolbox yet.”

Mayer says the most critical adoption step is deciding whether to adopt technology as standard operating procedure and make it part of the official toolbox. When that happens all employees will be trained on using it in the normal workflow. But some good ideas don’t fit the company as a whole, which is when Mayer says it’s important to file them as “best practices” rather than put them in the SOP toolbox. They shouldn’t be forgotten, because they may become more valuable later as the industry evolves.

Challenging Champions

Other firms challenge employees to go beyond idea generation and to lift ideas into usefulness by becoming their marketers and champions.

In a recent ENR guest column, Jason Kraynek, Fluor’s vice president for business transformation and innovation, described how the company’s “One-10-Times” approach grounds its innovation efforts. For an innovation to get company backing, the submitter is challenged and empowered to reach across the globe and find other supporters. Ideas under development are tracked on the company intranet, providing visibility into the ideas in the pipeline. Only after an innovation has been shown to be suitable for implementation on at least 10 projects and global support is found with people ready to champion and use it does an innovation gain standing to be considered for adoption.

“Idea generation and implementation are not successful if they are limited to one research and development center or isolated inside the technology division,” wrote Kraynek. “For innovations to be implemented and sustained, they must have ownership and engagement from across the organization.”

Focus on Achieving the Most Good

And finally, some technology leaders are learning from earlier disappointments by stepping back to question the very ways construction gets done and how people are taught to do it.

“Even failure is a success in understanding and being more pragmatic.”

– Tomislav Žigo, VP for VDC, Clayco

“We embarked on this task about pushing digital information into the field eight or nine years ago—really early on,” says Tomislav Žigo, vice president for VDC at Clayco. “We thought we could use it to evaluate subcontractor performance, identify most common issues and help us calculate statistical probabilities. It turned out we were not all that consistent in producing digital data, and the data that was collected did not have the significance we hoped it would. Now we are going through phase two, making it smarter.”

As part of that, Žigo says Clayco is re-examining the roles of its managers and their engagement with projects, with the idea of following the manufacturing model more closely and “talking more about process managers instead of project managers.”

“The biggest potential is that the construction industry can, with relative ease, make progress in eliminating factors that create unsafe work environments and remove humans from repetitive tasks that are prone to error,” Žigo says. “Robotics, machine learning and AI, if deployed in a smart way, with modest humble steps that are well thought through, can really change the way we do business.

“Even failure is a success in understanding and being more pragmatic when it comes to the next step. That’s internal knowledge you want to contain, and even nurture,” Žigo says.