The New Energy Market

Engineers, Contractors Building More Renewable Energy Power Plants

Mortenson constructed the 170-MW Beaver Creek wind farm for MidAmerican Energy. Company executives say as wind towers and turbines get larger, much of the assembly has to occur on site.

PHOTO COURTESY OF MORTENSON

Coal, natural gas and nuclear plants, long sources of baseload power, are losing some ground to cheaper renewable wind and solar generation, which are now providing 10% of the nation’s electricity.

PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Coal, natural gas and nuclear plants, long sources of baseload power, are losing some ground to cheaper renewable wind and solar generation, which are now providing 10% of the nation’s electricity.

PHOTO COURTESY GETTY IMAGES

Coal, natural gas and nuclear plants, long sources of baseload power, are losing some ground to cheaper renewable wind and solar generation, which are now providing 10% of the nation’s electricity.

PHOTO COURTESY BURNS & MCDONNELL

Coal, natural gas and nuclear plants, long sources of baseload power, are losing some ground to cheaper renewable wind and solar generation, which are now providing 10% of the nation’s electricity.

PHOTO COURTESY MORTENSON

The 32-MW Gila Bend project was built by Black & Veatch for utility Arizona Public Service Co. The state is third in the nation for solar capacity, with 3,400 MW of installed solar capacity.

PHOTO COURTESY OF BLACK & VEATCH

Solar power is becoming more popular as energy choice for some corporations, such as Apple.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Apple

In 2005, at the start of his career, engineer Ben Edgar was doing the same calculations on energy project after energy project—centralized power station to end user. “I thought it was going to be a long, boring career,” says Edgar.

Now Edgar, business development lead for distributed generation at Black & Veatch, might be calculating how much renewable power is needed to run a corporate client’s data center, how much building efficiency can offset energy use or how a microgrid will perform if a major transmission line fails—all possibly on a single project.

“I personally love all of the change in the industry,” Edgar says. “It forces us to mix the engineering and technical details behind the power generation with real business and economic issues. And how we solve those problems changes from location to location. I love all the chaos.”

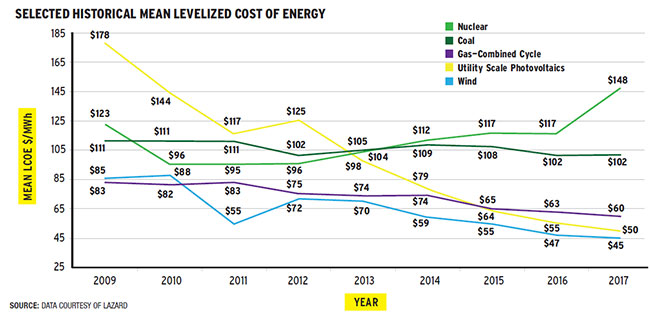

Driven by wind prices that, according to financial services firm Lazard, have fallen 47% since 2009, and utility scale solar prices that have plummeted 72% since that time, wind and solar generation have grown to 10% of the nation’s energy capacity from 2% in 2007, according to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Renewables have led capacity additions for power generation for the last three years, according to FERC, and wind and solar will account for 64% of all generation additions through 2050, even as subsidies for the renewables disappear, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). When hydropower and other renewables are included, the U.S. is running on 17% renewable power.

“It’s definitely a new day,” says John Olander, head of the transmission and distribution division of Burns & McDonnell. “We’ve been talking about this for quite a long time. In the last couple of years, it feels like it’s here. There’s quite a bit of momentum.”

Some states are way ahead of the trend: In California, there have been times where renewable energy, including hydropower, supplied more than 70% of the load; Texas runs on more than 50% wind power during some periods; and in less than 30 years, Hawaii expects to be 100% renewable.

Corporations are embracing cheap wind and solar to lower their costs and meet sustainability goals. Already this year, companies have entered into deals for more than 2 GW of renewable power, often sidestepping utilities that can’t act quickly enough to provide renewable power. Some are going a step further by creating distributed generation, or microgrids, that will allow their operations to continue even if the power grid goes out.

“I have seen more changes in the industry in the last five or six years,” than in the last 20, says Mark Donahue, vice president and general manager of the high-voltage transmission group at Mortenson Construction. “It’s going to take everyone to figure out what direction that this is heading."

The changes are causing growing pains for electric utilities. Ohio’s FirstEnergy confirmed late last month it will shut down three nuclear plants because those plants can’t compete with lower-priced natural gas and renewable energy. Nuclear plants can’t easily start up and shut down, meaning they have to keep operating even if the market price for power is below zero.

But engineering and construction firms see business opportunities in the changes and are expanding or creating divisions to build renewables and work with corporate clients.

“It’s hard to comprehend,” says Lou Graving, Black & Veatch vice president of renewables. “We are living it day in and day out.” Not too long ago, renewables were a small piece of the company’s power group. But now they’re one of the company’s four strategic initiatives. “The combined cycle group is definitely shrinking and renewables have seen dramatic growth in the last year and a half,” he says.

Value Proposition

The initial push for renewable energy was centered on reducing the use of fossil fuels and lowering the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. That push was accelerated by state renewable portfolio standards and the rollout of the Clean Power Plan in 2015. Even though the plan, to reduce carbon emissions 32% below 2005 levels by 2030, was stalled by courts and now by the Trump administration, it cast a pall over coal generation and put a premium on renewables, which are helped along by federal tax credits.

Today, though, renewables aren’t just about carbon reduction; they are also a value proposition.

“It’s a change in mindset,” says Patrick Malone, director of renewable energy for PCL Construction. “The solar industry has an energy solution for you whose terms are fixed for 20 to 25 years at competitive pricing. That’s a sound business proposition for any business person out there.”

The low prices convinced certified public accountant and Republican mayor Dale Ross of conservative Georgetown, Texas. “Money is money,” says Ross. Georgetown became the largest U.S. city to be powered by 100% renewables in 2015 after the city’s power provider couldn’t guarantee its electricity price from natural gas-fired generation beyond seven years. Wind developer EDF guaranteed a price for 25 years. The city contracted to purchase 194 MW of wind power from EDF and is building a 100 MW solar farm with NRG to handle future growth.

“Back then, first and foremost it was a business decision—we made a decision based on the facts. We put silly partisan politics to the side,” says Ross. Though he adds that the environmental benefits are a plus: “We all want clean air and water.”

“We are seeing the pricing of wind and solar and battery generation to be really competitive, and it will rely less and less on policy to keep driving that.”

– Mark Donahue, Mortenson

Georgetown isn’t an anomaly. Lower renewable and natural gas prices are squeezing coal power, which supplied more than 50% of U.S. electricity a decade ago. Now, coal-fired electricity accounts for only 30% of the U.S. portfolio and will be outstripped by renewables before 2040, according to the EIA.

The falling prices of wind and solar could start to push natural gas out in some regions as well. California and Arizona this year proposed moratoriums on new natural gas plants until studies are completed about the possibility of using renewables and storage to meet demand.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasts that by 2023, onshore wind and photovoltaic solar (PV) will be as cheap as new gas-fired plants. Five years later, new solar and wind will be cheaper to build and operate than existing natural gas plants.

“That’s the real tipping point—in three, five or seven years from now when new wind and solar is consistently cheaper than existing coal, gas and nuclear,” says Nathanael Greene, a senior policy analyst at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

It’s already happening in some places. An all-source solicitation by Xcel Energy last year to replace 660 MW of coal power in Colorado yielded bids for solar power that were lower than the cost of power from existing coal plants in the state, and bids for solar-plus-battery storage were cheaper than 70% of the existing coal sources in the state, according to analysis by Carbon Tracker. The utility and the state have yet to choose any projects.

“We believe that trend [of low prices] will continue to drive the market,” Donahue says. “We are seeing the pricing of wind and solar and battery generation to be really competitive, and it will rely less and less on policy to keep driving that.”

Between now and 2040, Bloomberg forecasts that $10.7 trillion will be invested in new power generation worldwide—but just 10% will be spent on coal and gas plants. The rest will be spent on new wind, solar, nuclear and hydro generation.

Related Articles:

Upgrades Improve Wind Farms' Performance and Bottom Line

Electricity Generated From Tethered Wings and Other Things

A Conversation with Energy Visionary David Crane

The Future of Baseload

Despite the growth of renewable power, traditional baseload generation from natural gas, nuclear and even coal is expected for years to provide a backbone to the electric grid to provide power when the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining.

New multibillion-dollar nuclear units being built in Georgia are unlikely to be abandoned for decades, and in Michigan, the state just approved a $1-billion natural gas plant.

“I think it will be a long time before we don’t have a fossil component to firm that intermittent power,” says Graving.

That baseload could consist of a few highly efficient plants in key locations to address variability, says Edgar.

“My personal thoughts are that in current and static mode, it would be incredibly tough today or in some very quick fashion to remove nuclear, coal and gas from the system,” says Olander.

Some states will move more quickly than others.

Hawaii, which had 27% renewable energy in 2017, has an ambitious goal of being 100% renewable by 2045. California is set to meet its 2030 goal of 50% renewable by 2020. New York plans to be 50% renewable by 2030.

“There are going to be opportunities in different parts of the country to get a feel for how this will work,” says Olander.

A 2012 study by the National Renewable Energy Lab found that with commercially available technology, the grid would be “more than adequate” to accommodate 80% of all electricity generation from renewables by 2050.

A 2015 paper by Stanford University civil and environmental professor Mark Jacobson found the U.S. could run on 100% wind, water and solar by 2055. A recent paper, released this year by a group of researchers at the Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford, found that wind and solar could, in principle, provide 80% of total U.S. electricity demand. But going beyond 80% would require more storage or more interconnected wind and solar.

Clyde Loutan, principal for renewable energy integration for the California Independent System Operator, which controls the California power grid and integrates a constantly changing amount of renewables onto the system grid, points to a study from 2014 he participated in that found renewable energy can provide even better control frequency, ramping capability and real-time energy balancing than fossil generation.

“We are going to have to rely on a lot of different solutions to make it work,” he says. “But if you ask me, we can do it.”

While regulations and investments in existing fossil generation may hold back some utilities and state regulators from moving more heavily into renewables, no such barriers exist for hundreds of corporations, which are building or buying renewable energy at breakneck speed to meet corporate sustainability goals. Since 2013, corporations have inked deals for more than 11 GW of renewable energy—the equivalent of 11 new nuclear units. More than half of Fortune 500 companies have greenhouse gas or renewable targets, and according to a PricewaterhouseCoopers survey, 72% of large companies in the U.S. are actively pursuing renewable energy purchases.

“The C&I [corporate and industrial] growth has been huge. It has been the number one renewable energy growth group in the country,” says Graving.

“Utilities can’t adjust fast enough. I think the desire is there, but it’s a difficult proposition to make such radical changes quickly.”

– Ben Edgar, Black & Veatch

In April, Apple achieved 100% renewable power at all of its own facilities worldwide, and now is pushing companies in its supply chain to convert to renewable energy. The company achieved its goal by building its own facilities when utilities couldn’t meet its request.

“They are not getting the products and services that they want from their utility and they are going out and getting it even if there’s a financial cost to them,” says Kevin Haley, marketing manager of the Rocky Mountain Institute’s Business Renewables Center, which tracks corporate deals and helps corporations and developers work to meet their renewable goals.

It’s up to renewable developers and consulting engineers to help the corporations navigate through the often-confusing world of power purchase agreements and grid interconnections.

“We’re developing solutions for those types of clients,” says Malone. “We are helping more of the C&I customers to provide direct connection and direct supply and energy.” As renewable prices keep dropping, Malone expects the C&I sector will continue to grow. Donahue at Mortenson says the company has created a separate group that focuses on corporate work.

At the same time, the consulting engineers are also helping utilities figure out how to provide renewable energy to corporations within regulatory confines.

“Utilities can’t adjust fast enough,” says Edgar. “I think the desire is there, but it’s a difficult proposition to make such radical changes quickly. It is taking longer than people want to wait. Every utility we are talking to is trying to figure out how to do that.”

The utilities are making progress by developing flexible programs that will allow them to provide renewable electricity without subsidizing it.

“We can’t cost shift on to other customers,” says Lisa Wood, vice president of customer solutions at the Edison Electric Institute, the trade group that represents investor-owned utilities. “We definitely recognize this as a trend.” Some corporate buyers are beginning to realize there are advantages to working with utilities, Wood said. “If you look at the West—California, Arizona and Nevada—there’s a lot of solar. They could put another solar farm there, sure, but would it make sense?” she says. “Let’s figure out another way to meet your goal.”

Such solutions could include constructing net-zero buildings, or participating in programs to reduce how much energy a company uses. “There’s no reason that these deals need to happen outside of the [utility’s] control or territory,” Haley says.

The growth of corporate renewables, however, could drive a massive change in the traditional regulated-utility-monopoly model that provides power to everyone. “Probably what you end up with is that commercial and industrial customers upend the political order and demand change,” says Greene, who cautions that such a move driven by corporations might not yield the best outcome for a society that depends on affordable, accessible power.

SOURCE: DATA COURTESY OF LAZARD

Huge, Huge, Huge

Donahue says corporate demand points to another trend he expects to continue to grow—distributed generation, which can be in the form of company- or community-specific microgrids that use company-owned generation.

“I think a lot of the corporate growth ties into where I see us going in five or 10 years. There’s a lot more interest in microgrids, distributed energy resources, batteries instead of generators,” says Donahue, referring to the C&I clients.

With a microgrid, wind and solar can be a primary source of power, and when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing, diesel generators can provide power, or batteries can store excess renewable generation and provide power as needed. Battery prices fell as much as 24% between 2015 and 2016, according to GTM Research. “I would say the rapid decrease of battery prices is pouring gasoline on distributed generation. It pushes more people to look at distributed generation solutions. More of those business cases make sense and become economical,” says Edgar.

Jack Griffin, vice president for one of Veolia’s energy services units, says, conservatively, microgrids will grow 15% over the next 15 years. The microgrids average about 5 to 15 MW each, he says. The demand for company-centric microgrids is driven not only by a company’s desire to add renewable power, but also to keep operating if electricity goes out.

“It’s huge, huge, huge. It’s a sustainable solution that gives companies the platform to integrate renewables. It’s that total package.”

– Jack Griffin of Veolia on microgrids.

“There is a growing interest. It is huge, huge, huge,” says Griffin. “It’s a sustainable solution that gives companies the platform to integrate renewables. It’s that total package.”

He says the power outages in Puerto Rico highlighted the possible benefits of microgrids. Many of the industries operating in Puerto Rico only had backup generation, not a solution that would allow them to continue to operate. Veolia and other companies such as Louis Berger are discussing building microgrids with industries in the territory.

“They don’t want a hiccup,” Griffin says of industry in general. Companies assign a cost per unit for the electricity needed to produce their product. Now, many are also assigning a cost per unit if the power goes out and they can’t produce their product, he says.

Utilities, with regulatory approval, are building microgrids as well, looking to determine the best way to operate them and integrate them into the nationwide grid. Later this year, ComEd will bring 490 customers onto its Bronzeville Microgrid in the middle of Chicago and will bring on 1,060 customers next year. The pilot program will create the first microgrid cluster in the world, as it will tie into a microgrid already operated by the Illinois Institute of Technology.

The microgrid signals a willingness by ComEd to test the waters of a new utility model for the future. That doesn’t mean, however, that microgrids are poised to supplant a traditional centralized grid.

“There are a lot of benefits being part of the normal grid—using power from utility-scale generation,” says Shay Bahramirad, ComEd’s director of distribution planning, smart grid and technology, and leader of the Bronzeville project. “It’s not one or the other,” she says. “It’s going to be a hybrid of both.”

The entire paradigm of electricity supply, storage and distribution is likely to be changed by a growing demand for electric vehicles. Bloomberg forecasts that as battery prices continue to fall, electric vehicles will dominate car purchases by 2040. That will increase demand for electricity, but electric vehicles could also catalyze more distributed generation as the batteries in the plug-in vehicles can be used to store the excess renewable power generated.

“If it shifts to more EVs, a significant load will be placed on the system. That’s on the horizon,” says Malone. “It’s something that people have to come to grips with—how to answer that demand.” But, he adds, electricity storage in those vehicles can also be a “big part of the solution.”

Labor Shifts

As the type of electricity generation evolves, so too will labor and construction practices. Already, there are almost 374,000 people working in solar technology—43% of the electric power generation workforce and more than double the number employed in the oil and natural gas generation sectors, according to a U.S. Energy Dept. report.

Rather than pipefitters and millwrights, the newer technologies need a different mix of labor, including electricians, robotics specialists and general laborers, the construction companies say. “The interesting thing about a solar farm is you have to envision an outdoor factory,” says Malone of PCL.

Graving agrees, “It’s more about materials management and is more like manufacturing in the field. We will have fewer workers, but different skills sets will be required.”

“If it shifts to more EVs, a significant load will be placed on the system. That’s on the horizon. It’s something that people have to come to grips with.”

– Patrick Malone, PCL Construction

Currently a typical 200-MW natural gas peaking plant takes more than 24 months and about 200 workers, at peak, to engineer and build. A 200-MW solar farm, by comparison, would take 16 months and require about 300 workers at peak, according to Malone. A comparable wind farm would take about 200 workers and be completed in less than a year, according to Mortenson.

Robotics will likely play a role in assembling new solar farms, and perhaps even installing some of the components. “We’re developing new methods from factory to field, the entire process,” Graving says. “We’re looking for ways to use lean methods to drive waste out of transportation, field and manufacture”

Innovations that haven’t yet been developed will drive new energy technologies and the ability to integrate everything into one cohesive system.

“We are in that transition phase,” Donahue says. “It’s going to take some entrepreneurial spirt to figure it out—that’s what’s exciting about it.”