Philips Arena Revamp Relies on Structural Redo

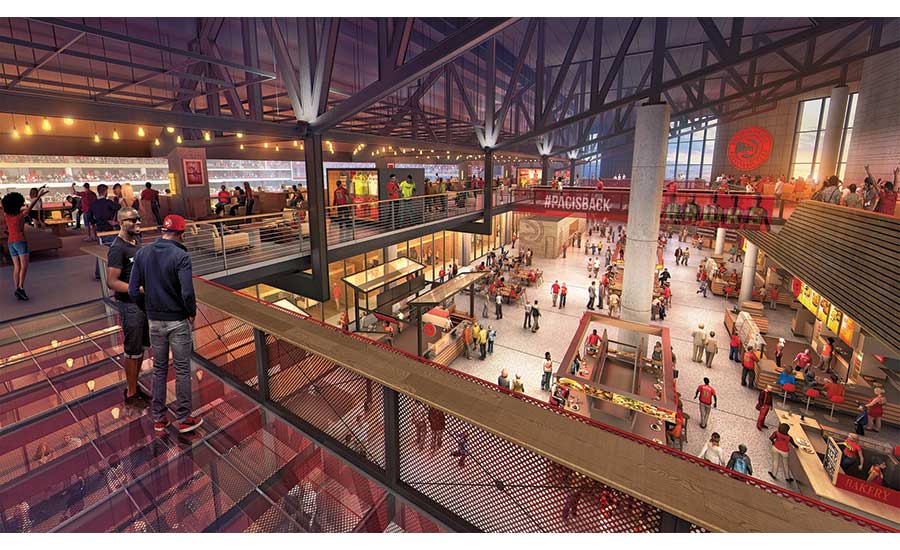

HOK’s design for new Philips Arena calls for more areas providing social interaction.

RENDERING COURTESY HOK

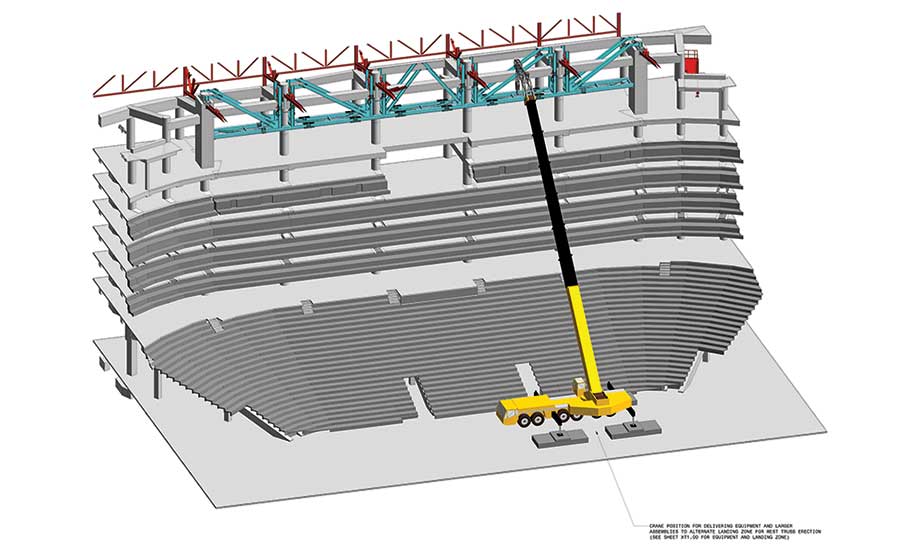

Erection of a new truss required significant planning and 3D scanning to execute.

IMAGE BY STANLEY D. LINDSEY AND ASSOCIATES

The stick-built truss required approximately 250 crane picks to put into place.

IMAGE BY STANLEY D. LINDSEY AND ASSOCIATES

The installation of the truss enabled the demolition of four columns and additional structural concrete.

PHOTO COURTESY TURNER CONSTRUCTION CO.

Don’t call the $192-million Philips Arena project a renovation. Though that’s its official moniker, the terms “rebuild,” “transformation” or “complete gut-job” would be more apt. That’s because contractors, designers and structural engineers, especially, are having to exhibit some fancy footwork and deft maneuvering as they completely tear out the heart of the Atlanta NBA facility—including a huge chunk of its structural system—as they install a completely new interior.

Among sport venues, the Philips redo is “unmatched in a lot of ways,” says Ryan Gedney, senior project designer with HOK. “The sheer scope and timeline is definitely on the upper level [in terms of] transformation. It’s a new venue.”

The National Basketball Association’s Atlanta Hawks believe HOK’s design is delivering what is essentially a new facility for the team. “By knocking down the walls and making it more connective and adding square footage, we were able to have a new building from the inside out,” says Thad Sheely, chief operating officer for the Hawks.

The project team’s main challenge was updating a unique design for the facility, which is two decades old. First, the arena featured a concourse that wasn’t completely circular, but instead horseshoe-shaped, and thus not fully extending around the interior’s perimeter.

More problematic was the original arena’s one-of-a-kind element, the four levels of luxury suites stacked along its west side. With these seating options falling largely out of favor to seating that offers more social experiences—think party decks—the hulking mass was a big problem.

Specifically, HOK’s renovation plans called for tearing out three levels of suites, from the second level up to the roof, in order to build other types of upper-deck seating featuring open views.

Tricky Truss

The task of eliminating four columns supporting high-roof trusses was a “big feat,” says Chris Christoforou, principal with Thornton Tomasetti, the engineer of record. The “play” the team designed comprised erecting, piece-by-piece, a 173-ft-long, 20-ft-high primary steel truss in a north-south direction to support the existing secondary trusses that would be left orphaned when crews removed four 36-in.-dia columns.

The approach of “building the chords, the diagonals and the verticals one piece at a time is very unusual,” Christoforou adds.

Erecting a truss carrying 1 million lb of roof load without touching the building’s envelope was the project’s biggest hurdle, adds Zach Olsen, senior project manager with the construction management joint venture comprised of Turner Construction, AECOM Hunt, SG Contracting and Bryson Constructors.

The truss’ location above seating that needed to stay in place for the time being was one challenge. Another was the schedule. Since the entire project was broken up into phases scheduled around the Hawks’ NBA seasons, contractors were left with an eight-week window in the summer of 2017 to erect the new truss. In that timeframe, more conventional methods, such as shoring down the remaining high trusses, wouldn’t work.

Further, because of the time crunch, the piece-by-piece construction of the truss had to go almost perfectly, says Olsen. To do that, “We used a lot of 3D scanning” to accurately document as-built conditions, he says.

“There was an extensive survey program before we even started fabricating the steel,” Christoforou says. “We had to adjust and modify some of the design details to accommodate the as-built conditions.”

“When you’re working 20 hours a day, a holdup for a single piece of steel that doesn’t fit correctly is a game-changer.”

– Zach Olsen, Senior Project Manager, Atlanta Joint Venture

Due to the schedule, which afforded little time to deal with problematic fits, crews needed to work nearly around the clock building and erecting the truss.

“When you’re working 20 hours a day, a holdup for a single piece of steel that doesn’t fit correctly is a game-changer,” he says. For instance, a concrete placement occurred just two days before a scheduled concert.

The truss erection required about 250 crane picks, Olsen estimates. The team’s 3D scanning was added to the project’s digital model, enabling contractors to create a 3D model for each pick showing crane placement and erection sequence.

Key to the effort was engineering and implementing the shift in load, which had to be done all at once, Olsen says. Contractors kept the existing columns in place prior to demolition and used eight jacks to preload the truss with 125,000 lb each, or a total load of 1 million lb.

“So we jacked the trusses, we transferred the load to the new truss and then we started cutting the four columns,” Christoforou explains. “And we only cut the portion that was sticking below the bottom chord of the truss. But that saved a lot of time in forced demolition.”

Estimating the existing load was trickier than one might imagine, Christoforou says.

“When you transfer a load, you make assumptions what the load up there in the roof is,” he says. While the roof structure’s weight was known, the impact of other installed systems was more ambiguous. “We have a range of load, but it’s never going to be exact.”

The final release of the load is the moment of truth, Christoforou says. “Because that’s the only way you tell exactly that you transferred the total load. It was a very close match.”

In fact, the variance from the estimate was just one-quarter inch, says Olsen.

Fast-Break Finish

Between mid-June and Oct. 15, contractors need to produce about $100 million of construction work, Olsen says. Crews are “building our way out of the facility,” he says, starting at the top of the structure and working down. “We have kind of a rolling approach culminating in that Oct. 15 completion date.”

“Folks will not recognize this facility as soon as they step through the doors,” says Olsen.

Adds Christoforou: “I can’t wait, actually.”