#MeToo in Construction: 66% Report Sexual Harassment in ENR Survey

Two-thirds of 1,248 respondents to ENR's first-ever survey report an incident in construction-sector workplaces, but industry gender bias issues are not clearly understood, universally accepted or easily fixed, the analysis shows.

The ironworkers’ union Be That One Guy program was on the cover of its magazine. Joe “Icepick” Moore (left), working with Shannon Russell, says “I’m not going to put up with it. I’m going to say something.”

PHOTO BY TARA GARNER

Ironworker Lisa Kientzy says coworkers on site have told her “we’ve got your back.”

Credit: Tara Garner

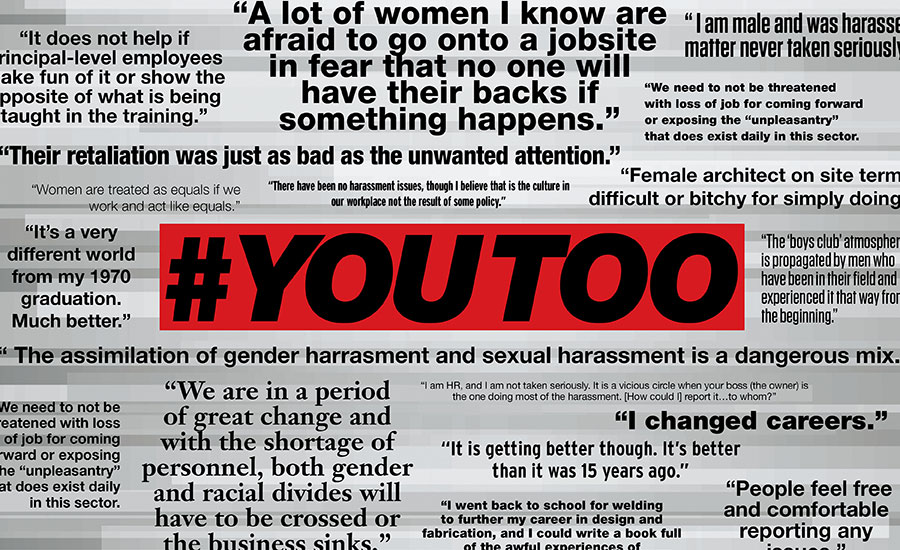

The personal stories and points of view on sexual harassment and gender bias in the construction industry are as varied as the 1,248 respondents themselves in ENR’s first-ever survey of a workplace phenomenon that has long plagued the industry but now comes front and center at the first anniversary of the #MeToo movement.

More episodes of unwanted physical contact or biased treatment are being acknowledged and debated, and generating workforce and management interest as employers struggle to create cultures that will keep critical talent in place, push needed diversity and build the future pipeline.

The survey results indicate the extent of the industry’s problem, with some 66% of respondents reporting they have faced sexual harassment or gender bias in the workplace, and nearly 60% saying they have witnessed it.

These issues have appeared in ENR and Architectural Record—its sister publication that collaborated on the survey—long before the first revelations involving Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein and hundreds of other business, media and academic leaders gained intense media attention last year.

|

Related Articles |

Now the publications take a deeper dive into how employers and their staffs in the architecture, engineering and contracting sectors are both confronting issues and developing proactive solutions.

Click here to read an architecture-specific analysis on line appearing in Architectural Record magazine and here to learn how architecture students are propelling needed culture change on campus.

Accusations this past spring by multiple women of inappropriate contact and other harassment by award-winning architect Richard Meier revealed to the New York Times gave the problem an industry face and began generating more intense debate and a flurry of actions.

After a several-months-long leave of absence, Meier will "step down" from firm management, his architecture practice announced on Oct. 9, although he will be involved with its activities.

The attention in the architecture community generated a large response to the ENR-Architectural Record survey, with individuals in that community making up about 48% of respondents. They included at least one of the women who had publicly claimed sexual harassment by Richard Meier.

The concerns—along with new initiatives—also were voiced in May by nearly 700 participants at the Groundbreaking Women in Construction conference in San Francisco, presented by ENR and law firm Peckar & Abramson. Small groups shared personal experiences during informal lunch discussion sessions.

To gain a broader perspective—across gender, age group, employer type, job function and career level, among other demographics—the magazines hosted the online survey on their websites for six weeks this summer. Publicized by social media and industry groups, it sought responses on the prevalence and type of sexual harassment and gender bias, how incidents were handled by those involved and responsible and larger issues around building a diverse and productive workplace.

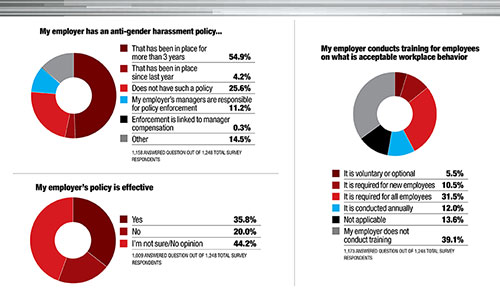

Responses were anonymous to encourage as much candor as possible on a complex, personal and sensitive subject, but many respondents also agreed to be contacted. In multiple-choice and open-ended questions, they provided a wealth of data (see chart below and farther down) and individual narratives that reveal details on nagging incidents from the past and present, insights on persistent problems, and proactive thinking and programming to change behavior.

By the Numbers

Respondent demographics were diverse. They worked in craft, technical, business and management roles at all levels in a cross-section of private and public construction industry employers of all sizes and specialties in the U.S., Canada and overseas. Almost one-third of respondents were men, including some that communicated issues stemming from their sexual orientation. “I was fired for being gay after 10 years of managing the office … and was threatened [it would] ruin my career if I told anyone,” said one veteran male architect executive.

When queried about personal experiences with sexual harassment, one-third of respondents reported none in their construction careers.

“I was groped by my foreman and then told I could ruin a man’s career if I talked too much … I got laid off a day later. There have been times when I was genuinely scared for my safety and no one cared, and when I spoke up I was penalized.”

– Survey respondent: Female craftworker in the southeast U.S., age 18-30

Among the rest, incidents reported at jobsites and in office settings were about evenly split, at 36.2% and 37.5%, respectively.

About two-thirds of the 76% of survey respondents who characterized a sexual harassment experience, pointed to inappropriate personal requests, questions, jokes or innuendo, while 42% marked gender-different responses from a supervisor.

About 30% characterized the harassment as inappropriate, unwelcome or unwanted physical contact.

Some survey respondents voiced confusion in definitions of and responses to gender bias and sexual harassment. One male educator in the Midwest said that in some circumstances, an “accusation seems enough to convict without full investigation.”

The ENR results parallel other sectors. In a major 2016 report, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) found that while only 25% of women surveyed characterized an experience as sexual harassment, 75% had experienced behaviors that can be described as harassment, such as unwanted sexual attention and coercion, suggestive comments and derogatory language, says Romila Singh, a workforce trends expert and associate business school professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. “The report also described that regardless of whether or not women label such unwanted conduct and offensive comments as sexual harassment, they all suffered similar negative physical, psychological, health and work consequences,” she says.

In a June report, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found that 58% of all female faculty and staff in academia experienced gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention or sexual coercion. It noted that 25% of female engineering undergrads and graduate students in the University of Texas system were harassed by faculty or staff. “There is no evidence that current policies, procedures and approaches—which often focus on symbolic compliance with the law and on avoiding liability—have resulted in a significant reduction in sexual harassment,” said the academies.

A U.K.-based survey in 2014 by financial consultant PWC of 25,000 men and women aged 28-40 reported construction as nearly the worst business sector for both sexual harassment and nonsexual bullying, topped only by the military for the former and by the media and entertainment sector for the latter.

‘Genuinely Scared’

Some ENR survey respondents described graphic and intense incidents. One 20-something craftworker who reported groping by a foreman and a layoff notice the next day said she was “genuinely scared” for her safety and “no one cared.”

A female architect from the Midwest in her 30s or 40s rebuffed repeated advances from a boss both at work and on out-of-town trips. She said she “confronted him very sharply and strongly and called him out on all actions he had taken.” That resulted in him “taking me off projects one by one until he had basically stripped me of my position. I informed his partners who … did nothing. I eventually resigned and started my own company.” Said another female architect: "The problem is a man would never feel the same physical threat as a woman does when they are being verbally abused. One out of five jobs is like this."

Despite threats of physical or career harm, most survey respondents said they did not take steps to report the harassment or punish the alleged perpetrator.

“The construction industry is predisposed to workplace sexual harassment due to several factors: gender disparity, marginalization, ‘macho culture,’ normalized behavior and outdated attitudes.”

– Stuart Binstock, CEO, Construction Financial Management Association

Nearly one-third of respondents shared harassment incident details only informally with a colleague, while 26% reported saying nothing or taking no action. About one-fifth of those answering the question said they alerted a manager and 12% contacted human resources. For nearly 14% of respondents, leaving that workplace permanently was communicated as their only remedy.

Speaking to the psychology of sexual harassment at a New York City forum on the subject last spring sponsored by the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, Julie Kantor, an executive coach and consultant, told seminar attendees that incidents may get hidden “under the auspices of creative tension,” and that women “have a tendency to do nothing … and just hope it goes away.”

Fear of being ignored, ostracized or retaliated against was a key determinant.

The academies’ analysis confirms that “women cope with sexual harassment most often by ignoring or appeasing the harasser and seeking social support.” Respondents noted challenges for those in small firms or those without an HR function or some other clear incident-reporting process. “It becomes difficult to say anything when there isn’t a system in place where ownership or senior management are in check,” said one respondent, a young male architect. “When it’s a client, this becomes even more complex. We are a service-based industry, so when those we serve become a part of the problem, the only solution is to be taken off of a job.”

Time has helped somewhat, said one veteran female manager respondent working for a specialty contractor whose workplace incidents date to the 1970s, 80s and 90s from previous employers. Then "there was fear and shame … blaming yourself for getting into this situation and the knowledge that my reputation would be put on trial and my life ruined," she reported.

But she added: "I would still consider reporting a sexual harassment situation to be a career killer unless you have a union to protect you. I am forever grateful to the women who have had the courage to come forward and bring this issue to the forefront."

Read one woman engineer's story of speaking out about unwanted physical contact on a jobsite.

Asked if their employers had responded to sexual harassment concerns, only 35% (of the one-third of respondents for whom the question applied) said yes. More than 54% indicated the response was no or other.

For those who could answer, nearly half of respondents said an alleged sexual harassment perpetrator denied the allegation, with about 11% in total indicating they had received a written or public apology.

One respondent, a 20-something project manager from Canada, settled a sexual harassment claim through a company-brokered nondisclosure agreement. She said such arrangements should “be handled by an unrelated third party,” claiming that internal HR departments “are not trained to support staff who have been sexually harassed.”

But said one human resources manager in a large industry firm: "I am seeing a heightened sense of awareness, and leadership speaks more openly about the realities of harassment."

According to new statistics released by EEOC that surprised some legal observers, the agency in fiscal 2018 filed 66 harassment lawsuits—including 41 alleging sexual harassment—more than 50% more than in above the previous year. New claims filed to the agency alleging sexual harassment jumped 12% over 2017—the first increase in eight years. EEOC also said it recovered nearly $70 million for claimants in 2018, up from $47.5 million the year before.

State Actions

States are also ramping up sexual harassment prevention rules now for employers in everything from worker training to bans on secret arbitrations and brokered settlements and reduced or eliminated time limits for claims.

Amendments enacted in April to New York City and state laws expanded workplace sexual harassment bans to outside contractors, vendors and service providers as well as outlawing nondisclosure clauses unless claimants say otherwise, according to an update by city-based law firm Tarter Krinsky & Drogin. State law now extends the time to file a misconduct claim to three years, from one year.

But the state just announced it would delay its employee-training deadline to October 2019 from January 2019 and dropped a requirement to train new employees within 30 days of hire.

“The fact that we still have to explain to people in 2018 that harassment is unacceptable is beyond sad. Dragging our feet on this, and related issues, is a sign of how behind the times this field is.”

– Survey respondent: Architect, age 31-45, New York-New Jersey

Richard Steer, partner in the firm’s employment and labor practice, says that flexibility will make it easier for contractors with fluctuating workforces, but he says the state’s model harassment complaint form does not enable a sufficient investigation by employers.

“Our members have had training for years,” says Denise Richardson, executive director of the General Contractors Association of Greater New York. “I don’t think we will have the trouble that other industries will have.” She contends that “construction is a production-driven environment. Sexual harassment takes a backseat in a culture where everyone is expected to do their share and pull their weight.”

California goes further in a new sexual harassment protection law enacted on Sept. 30 that will take effect on Jan. 1, says Andrea Oxman, a Los Angeles employment attorney.

It sets new training rules for firms with at least five employees, bans most secret pacts and clarifies legal standards for claims, including required jury resolution. Says Oxman, “We haven’t seen the crest of the wave of sexual harassment litigation.” In Maryland, employers with more than 50 workers must now disclose each year the number of sexual harassment pacts they enter.

“We have to raise up the good guys.”

– Vicki O’Leary, General Organizer, Ironworkers’ union, referring to its new Be That One Guy bystander training program

Bills also are pending in both houses of Congress to eliminate or curtail secret arbitration agreements, that would apply in other states.

One little-known facet of the Trump administration tax cut passed last year also restricts employers from deducting costs of sexual harassment pacts, but observers say other provisions of the law pertaining to allowed deductions could limit the amount of settlements for plaintiffs.

While prosecutions have been limited by statute of limitations or plaintiffs not pressing cases, some employers are rethinking how far back incidents can be probed. New Jersey-based Rutgers University announced in early October that it will drop its statute of limitations on case filings—formerly just two years—which while meeting state civil code, was “inconsistent with both our practices and our values," said President Robert Barchi.

Facing the flurry of new mandates, construction sector groups say they’re supporting member firms in combatting harassment.

The American Institute of Architects' board approved last month an anti-abuse and anti-harassment resolution passed at its June convention, to amend its ethics code.

One survey respondent, who is president-elect of a local AIA chapter and on a state anti-harassment task force, is pushing efforts for smaller firms with no HR staffs to understand the changes and devise programs to meet code rules and improve workplace interactions. Activists like Cynthia Kracauer, executive director of the Beverly Willis foundation, also seek to tie sexual harassment to state licensing rules for architects.

Industry groups such as American Subcontractors Association and the National Electrical Contractors Assocation also have hired outside consultants to deliver training to member firms though webinars and other approaches.

AGC companies “are more concerned about [sexual harassment rules] now and are seeking more resources from us,” says Claiborne Guy, director of employment policy and practices. Its meeting with the Construction Financial Management Association Oct. 24-26 in Las Vegas will include a focus on the topic, says CFMA President and CEO Stuart Binstock. “Sexual harassment in our industry is real and it is prevalent, regardless of whether it is openly discussed,” he says.

“In New York ... if the conduct is unwelcome, even if you didn’t intend to make the person uncomfortable, it wouldn’t save you. 95% of cases don’t go to trial. You don’t have a jury saying who’s right.”

– Richard Steer, Partner, Employment & Labor Practice, Tarter, Krinsky & Drogin, New York City

Unions, among others, also are boosting “bystander training” to improve sexual harassment vigilance and empower incident intervention.

The ironworkers’ international union is rolling out its Be That One Guy program under its safety training mission. It enlists the support of male ironworkers “who are not afraid to speak up and tell a bully to knock it off,” says Vicki L. O’Leary, union general organizer for safety and diversity, who launched the effort this year. A harassed person and one doing the harassing can’t focus on safety, she says, and it’s “upsetting to those around them.

The program’s goal is a cultural shift. “We have to raise up the good guys,” O’Leary says. In a two-hour class on diversity that is included in the ironworker safety training course, “we talk about unpacking the knapsack of gender inequality,” she says. “We ask men if they have fears of walking to their car as they leave the jobsite.” So far, about 170 managers have completed training. One ENR survey respondent was aware of the Be That One Guy program but commented that it was not in effect widely.

The union magazine, The Ironworker, with a circulation of 150,000, featured the Be That One Guy program as the cover story of its September 2018 issue. For the first time, a female ironworker, Lisa Kientzy, a fourth-year apprentice with Local 396 in St. Louis, was on the cover. “Our brothers are vital,” she says. “We need the support to know we have someone on our side.”

Joe “Icepick” Moore, a 20-year veteran with Local 433 in Los Angeles, puts a face to “that one guy,” saying, “I’m not going to put up with” harassment, bullying or intimidation. “I’m going to say something.”

“Very rarely have I experienced gender bias on a construction site. If you are respectful, contractors have no issue working with women in a position of leadership.”

– Survey respondent: Female architecture firm owner in Canada, age 31-45

Even with such efforts, some survey respondents and others worry about #MeToo movement impacts on industry relationships.

“I have been harassed in every job I have ever had, and it was something that just had to be addressed at the moment,” says Deborah Grubbe, president of consultant Operations and Safety Solutions in Pennsylvania, a former engineering project executive at Dupont and BP and member of the National Academy of Construction since 2013.

Noting concerns now voiced by male colleagues about one-on-one interactions with female professionals, she says “cross-gender mentoring is essential” in the industry, “so I worry that this kind of attitude will hurt the women who are coming up behind me.”

Adds a survey respondent, a Generation X male contractor executive: “The overreaction to normal human interaction is ... working against the goal of equal collaboration.” He adds that, as a result, women may not receive “direct and honest feedback.”

In general, the majority of survey respondents says the construction industry still has its work cut out in understanding and resolving sexual harassment and gender bias challenges, with nearly 63% concluding that sector-wide efforts are moving too slowly.

The lingering issues “are unacceptable on both a human and business level,” said one respondent, a female engineer at a small East Coast firm. "When people are distracted from their work [those victimized or perpetrating], they are not producing to the best of their ability. This is weakening the industry without question."

Data management by Andrea Pinyan