While attending the Juilliard School’s pre-college music division, Frances Halsband had an epiphany.

“I’m there in this artistic bubble and eventually realized I was not going to be a great pianist,” she says. “I felt isolated at Juilliard and decided I wanted to be more engaged in the real world.”

Halsband soon left the musician’s life and, in 1961, went off to Swarthmore College. There, she had another epiphany. It began with some impatience that students were just sitting around moaning about the war in Vietnam. She then noticed that her architecture-student friends at the University of Pennsylvania “never had time for suffering and angst.”

She started hanging around them, helping build models. Soon, she left Swarthmore for Columbia University, where she earned a master’s in architecture.

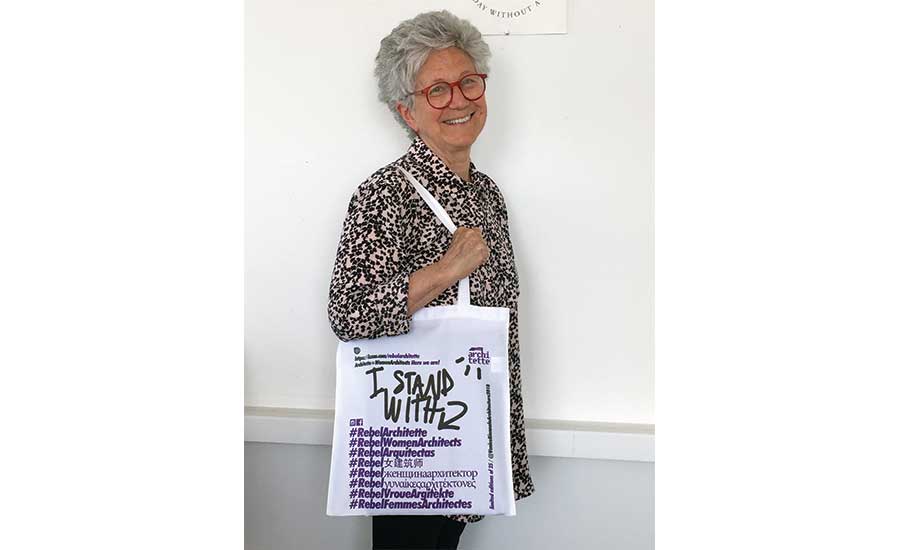

Fast forward 45 years to last May, 11 months after Robert Kliment—Halsband’s husband and co-founder of Kliment Halsband Architects—had died. With extra time on her hands, Halsband decided she wanted to do something meaningful. So she rallied 600 signatories from the American Institute of Architects’ 3,000-member College of Fellows and, at the June business meeting, introduced the anti-abuse and anti-harassment Resolution 18-16 to amend the AIA Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct. It passed almost unanimously.

In May, Halsband had sent an initial email about the resolution to 50 fellow AIA fellows. The header was, “Oops, I am becoming a revolutionary.”

The email initiative exploded. Soon, she had more than 500 replies. “This is so important,” said one. “It would be an honor to sign,” said another.

In September, the AIA board of directors ratified Resolution 18-16 and modified the AIA code of ethics. It now states that members “shall not” engage in harassment or discrimination in their professional activities on the basis of race, religion, national origin, age, disability, caregiver status, gender, gender identity or sexual orientation.

At first, Halsband’s crusade was about women. Then, it became about people. Her rationale goes back to a problem she has with the women’s movement in architecture. She says it makes it too easy to blame a situation on being a woman. “Being a victim is not a strategy for getting ahead,” she says.

Without playing the victim, Halsband has broken through some glass ceilings for women. She was the first female dean at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture and first female president both of the AIA New York and the Architectural League of New York.

Her client Michael L. Marin, surgeon-in-chief for the Mount Sinai Health System, calls Halsband “creative, thoughtful, vigorous in her drive for equality, and most importantly, human.”

In December, Halsband and her Resolution 18-16 cohort, Betsey Olenick Dougherty, managing principal of Perkins Eastman/Dougherty, received an AIA presidential citation. “The message was clear. Change was demanded,” said Carl Elefante, 2018 AIA president, in his Dec. 7 letter to the anti-abuse duo.

Not one for sitting on the sidelines, Halsband is plotting her next activism, which remains a secret.