Historic Whiskey Row Facades in Louisville Connect To Urban Bourbon Hotel

Hotel Distil and Moxy are being constructed in the former location of the J.T.S. Brown warehouse on W. Main Street in Louisville.

RENDERING COURTESY OF HKS HOSPITALITY

AECOM Hunt laser-scanned the two adjoining facades in front of the site to monitor movement during construction and coordinate connecting the building’s tower to the steel bracings holding them up.

LASER SCAN COURTESY OF AECOM HUNT

While Hotel Distil faces Main Street, the event spaces for Moxy are along First Avenue and Washington Street, making the “back” of the building its face.

PHOTO BY JEFF YODERS/ENR

HKS Hospitality used the openings in the historic facades as skylights for Hotel Distil’s bar, restaurant and curbside dining spaces.

RENDERING COURTESY OF HKS HOSPITALITY

The coordination model allowed AECOM Hunt to install a complicated web of piping, ducts and wall studs and two separate circulation systems on a tight schedule.

PHOTO BY JEFF YODERS/ENR

Clashes and errors were eliminated in design stage while creating the BIM 360 Glue coordination model.

3D MODEL COURTESY OF AECOM HUNT

Nineteen whiskey distillers, wholesalers and other liquor businesses called the 100 block of Louisville’s West Main Street home over the last two centuries.

Whiskey Row was known more for the business of warehousing barrels and loading and offloading them to barges on the nearby Ohio River than for the actual distilling of Kentucky Bourbon, but the block still was important enough to be placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010. In July of 2015, though, three of those historic buildings burned to the ground, incinerating previous renovation plans with them. All that was left behind were the cast-iron, Chicago-style facades saved by 80 Louisville firefighters. Emergency crews propped them up with steel supports.

Many developers balked at trying to build anything behind the heavy, still-protected remains of the buildings. The block was never a good candidate for facadectomies even before the fire. The 1860 facade of the J.T.S. Brown Warehouse at 115 W. Main couldn’t be changed at all and even bore the name of the distiller who later became a part of the Brown & Foreman Co.

But a plan was developed “to celebrate and embrace the culture (of Whiskey Row) and those historic facades … they have a history and a story to tell that goes back to the Civil War era,” says Aubrey Hartman, Vice President and Hospitality Designer at HKS in Dallas and lead designer of the $100-million, nearly 200,000-sq-ft hotel project being built behind the facades. “The history, everything all the way through to the fires that ravaged that block and those buildings just a few years ago needed to be respected and reflected in the design.”

The square of land at the corner of Main and First streets is only a block from the KFC Yum! Center arena and only a few more blocks from the newly renovated Kentucky International Convention Center. It was prime property for another hotel. Developer Steve Poe, CEO and founder of Poe Cos., had experience developing Louisville’s 620-room Marriott convention center hotel and the well-received Aloft Hotel directly across the street, but he was initially skeptical.

“When we first started looking at this site and started talking to my partners [White Lodging of Merrillville, Ind.] about it, as a developer, all we could see was dollar signs,” Poe said when announcing the project. “Facades to save, tight sites, historic structures to build around, streets to close … we recognized it was going to cost more, but we saw opportunity. Ourselves and the design team, we started embracing what’s here.”

Poe and White quickly realized that downtown Louisville was going through a transformation of its own. Washington Street, Poe said, was becoming more edgy and hip, but any design needed to respect the history of Main Street. The answer was two hotels. Hotel Distil, an upscale hotel that’s part of Marriott’s Autograph Collection brand, and Moxy, a 110-room hotel brand that began in Europe as Marriott’s answer to hostels and Airbnb and that has become popular with younger travelers. Both hotels had a place in the plan. A 14-story tower includes rooms for each of the hotel brands on each floor, but Autograph’s Hotel Distil and its public and front-of-house spaces engage downtown Main and the historic facades while Moxy engages and interacts with the younger crowd on the other side of the block facing Washington.

Rather than tie the historic facades directly to the front of the building, HKS created a design that sets them back and incorporates the existing steel supports into the building’s frame near large, open spaces rather than hide them.

“We kept our building pulled back from those historic facades and we connect to them only via a skylight, which is over the Autograph/Hotel Distil restaurant at the base of those facades,” Hartman says. “It was really important for us to create experiences for our guests to interact with the facades in different ways. Dining in the Autograph/Hotel Distil restaurant, that’s their perspective looking up through that skylight.”

There’s also a roof terrace for Hotel Distil that’s one level up from Main Street, immediately behind the facades and a covered amenity terrace for outdoor events.

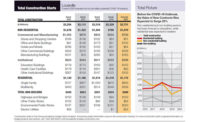

Ground was broken on the dual hotel in late November 2017. General contractor AECOM Hunt was faced with not only fitting all 198,159 sq ft and the program of both hotels into the narrow footprint, but the schedule was also a quick one, requiring that the hotels be able to open by the end of October.

AECOM Hunt’s Indianapolis office laser-scanned the three facades and built a construction model of the plan in Autodesk Revit from the design model.

“The reason we laser-scanned it was to see if we could monitor the facade to make sure it wasn’t shifting during construction,” says Bryan Hastings, VDC technician with AECOM Hunt.

While the dual hotels could use the same mechanical systems to serve the rooms of both brands, they still required separate elevators and circulation systems to their event spaces. As a result, coordination became more difficult in some of those spaces, a problem that was tackled while still in the design phase.

“The lower level, Level L, the one that the Moxy lobby is in, has so many plumbing mains, pipes and electrical lines that we had to fit into it, that it took the longest amount of time to coordinate of any part of the project,” Hastings says. “It looks like a mess of spaghetti in some of the areas [in the model]. We spent a lot of time down there with the design team moving stuff and asking if we could have more space in certain areas.”

The coordination effort is paying off during actual construction. The concrete structure has already topped out and AECOM Hunt’s project director, Jonathan Carpenter, expects it to be completed on time thanks to the coordination model being used as a reference on site.

“We can do everything from create a simple model [for our subcontractors] to show the exterior skin to a complete 4D or 5D model incorporating time and cost with all of the coordination in it,” Carpenter says.

AECOM Hunt is using its model for construction scheduling and just-in-time delivery of materials. Main Street only had to be closed for a few days during installation of utilities, assuaging Poe’s fears about the site. The majority of the building’s exterior skin is solid brick-faced precast panels with punched windows which were being set in place almost immediately as they arrived in mid-December. HVAC ductwork and insulation panels were also being installed immediately after delivery.

“The goal is on-time deliveries for as much of the material required to construct the project,” Carpenter says. The minority of the exterior skin is a copper metal panel facade that’s being installed on the Main Street side above the historic facades.

“All the materials we looked at and studied, we wanted them to have a relationship back to the history of Whiskey Row,” Hartman says.

The interior design of the Distil lobby carries forward this concept, incorporating blown glass pendant lights that evoke the local history of glassblowing for use in distilleries. Alan Orb, the owner’s representative for the Poe-White partnership, said they were pleased with the evolution of HKS’s design and Flick Mars’ interior design.