Risk Management

How Texas' Uncommon Law Is Different on Design Defects

The state's subcontractors and suppliers are looking for a legislated change

Unlike in Louisiana, only traces of the French-influenced legal approach remain in Texas.

IMAGE OF NAPOLEON COURTESY OF WIKIMEDIA COMMONS; TEXAS GRAPHIC COURTESY OF GETTY IMAGES

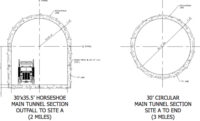

A case involving the Dallas Area Rapid Transit System reinforced protection for designers over defective plans.

PHOTO COURTESY OF DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT AUTHORITY

With land surveys, contractors often expect some information will be missing. But how much? Fifteen years ago, El Paso Corp. decided to replace a 68-mile-long pipeline with a new one that would carry butane from Corpus Christi, Texas, to inland Air Force bases. The energy company hired a Houston-based survey mapping firm to draw the route with rivers, roads and crossing rights of way. In all, the mapping company counted 280 survey crossings included in the bid package. No one pretended the count was final, and El Paso encouraged potential bidders to do their own survey.

Coral Gables, Fla.-based MasTec, at that time a newcomer to pipeline projects, hired an industry veteran who conducted a flyover of the route, but much was missed, court documents show. MasTec submitted a bid of $3.69 million, well below the average bid of $8.1 million. It signed a contract in 2003 where it took the risk for overruns.

Ever since a landmark 1907 Texas case and a landmark 1918 federal case, Texas contractors working on pipelines, office towers and light-rail lines have faced competing judicial precedents in similar cases involving design errors.

In the end, MasTec had to contend with more than 794 unknown crossings in the pipeline route and the extra welding that would be required, and it sued to recover its losses.

In the rest of the U.S., companies in MasTec’s position could expect a favorable court verdict and some recovery—despite the language in the contract about overruns—because of a 100-year-old legal doctrine widely observed in U.S. courts. It holds that the owner is responsible for the basic accuracy of the plans on which the contractor bids.

In this case, MasTec won the first round in a trial court, but El Paso prevailed in an appeal before a panel of state court judges in 2013. The appeals court victory provided another confirmation that Texas, as far as construction law is concerned, is a little different.

Ever since a landmark 1907 Texas case and a landmark 1918 federal case, Texas contractors working on pipelines, office towers and light-rail lines have faced competing judicial precedents in similar cases involving design errors. One favors owners, the other contractors. This year, Texas subcontractors believe they can win support from state lawmakers for a statute that will unify the treatment of Texas design defects under the doctrine that followed the 1918 federal case.

The subcontractors have found some unusual support for their bill in the Construction Law Journal. A recent article about the 1907 Texas precedent shows it may have been tainted by a tangle of conflicting interests, and was not, as previously thought, based purely on disinterested legal reasoning.

The 1907 Texas decision in Lonergan v. San Antonio Loan & Trust Co. was understood by some to have been a reflection of French-influenced Spanish common law that survives in Texas, which once belonged to Spain. The Spanish influence traces its roots to the six-year period when France, under Napoleon Bonaparte, controlled Spain. Unlike Louisiana, where the French code still figures prominently in state law, Texas in 1840 adopted English common law as the basis of Texas’ system. But elements of the French approach remained.

The 1907 case pitted the San Antonio bank against Chicago developer Thomas Lonergan, who built an office building for the bank in San Antonio, only to later see it collapse in a heavy wind and rain storm.

Evidence introduced at the trial suggested that a defect in the architect’s drawings may have played a key role in the collapse. To support the five-story building, the architect had planned to use steel beams tied into an adjacent building, known as a “party wall,” according to the journal article.

The architect later reversed course, declared the plan unsound and, after the prime contract had been inked, issued new drawings modifying this part of the plan. Lonergan’s foreman denied ever receiving the modified plans. Justice Thomas Jefferson Brown went on to deliver the ruling, stating that Lonergan was liable for the design defects that caused the collapse.

The journal article, by attorneys Fred D. Wilshusen, Misty H. Gutierrez and Jacob B. Damrill, all employed at the same Dallas-based construction law firm, explain Brown’s reasoning. At the core of Brown’s argument was the principle of the “sanctity of contract.” Barring fraud, competent people should be able to enter into contracts and be required to fulfill them, with no implied warranty that would make the building owner or architect liable for design defects.

Well-Connected Insiders

The details of the conflict show another side of what was decided. Chicago builder Lonergan faced off against a well-connected and well-heeled set of San Antonio elite insiders. Depicted by the plaintiff’s lawyers as a ne’er-do-well, Lonergan seemed to confirm the impression by not coming back to town after the building collapse to testify at the trial.

“Lonergan appeared to be the wrongdoer who did not accept its responsibility,” write lawyer-authors Wilshusen, Gutierrez and Damrill.

The bank, in contrast, enjoyed connections to the city’s movers and shakers, including Brown, the judge overseeing the case. George Brackenridge, a prominent businessman and philanthropist, headed the bank, while its vice president, Leroy Denman, had previously served alongside Brown on the Texas Supreme Court. He also apparently planned to rent space in the building for a separate venture.

Another member of the bank board had served as president of the state’s bar association, while the architect of the ill-fated building, Alfred Giles, was well-known to the San Antonio elite, having designed many of their mansions, the authors note. Giles had owned a ranch with his brother-in-law, John Herndon James, who also happened to be the chief justice of the state appeals court that had handled the Lonergan case before it moved to the Texas Supreme Court.

Lonergan, write the journal article authors, went up against some of the most well-connected citizens of San Antonio at that time, and “it is no secret that Texans can sometimes be intolerant of outsiders.”

About 10 years after the Lonergan case, the U.S. Supreme Court took up a case involving a contractor, George Spearin, who sued the U.S. Navy over a Brooklyn drydock project gone bad. The contract, signed in 1905, required Spearin to relocate a sewer line and build the drydock, to be used to repair battleships, according to specifications laid out by the Navy.

A year into the work, the combination of a heavy downpour and high tide flooded the dry dock. Spearin refused the Navy’s request to repair the sewer and finish the drydock. Consequently, he lost the job. Spearin later sued for unreimbursed expenses and lost profits, with the case winding up before the Supreme Court.

Spearin’s claim was bolstered by the fact that the Navy knew, when it was drawing up plans for the drydock, that another sewer line was connected to the relocated sewer line and, as a result, partly responsible for the flooding. Furthermore, Navy officials never informed Spearin that the area was flood-prone.

When the Navy required the sewer to be built according to certain specifications, it in essence “imported a warranty,” the law journal authors note.

Touchstone of Construction Law

The ruling in United States v. Spearin, written by Justice Louis Brandeis, is one of the touchstones of American construction law. While it isn’t well known outside the industry, Spearin helps define the still contentious relationships among owners, designers and contractors as much as possible, establishing that owners basically warrant the sufficiency and buildability of plans provided to contractors.

“The issue boils down to, ‘If you tell me to build this way and guarantee it works, and if I rely on the fact you told me to do it that way, and I do it that way, you can’t require me to guarantee that what you say will work,’ ” says Fredric Plotnick, an attorney, scheduling consultant and college professor.

Lower state court judges must follow precedents set at the state appellate level as long as the facts of a case are similar. Over the years, Spearin’s doctrine was taken up by states across the country, including Louisiana and Texas to some extent. A spate of court decisions in Texas from the 1970s through the early 2000s moved steadily in Spearin’s direction, either ignoring Lonergan altogether or citing it, only to come down on the side of implied warranty on the part of the owner and architect for errors in building plans.

The Austin County Court of Appeals in 2003 actually cited Spearin directly in a decision in a court case involving a spat between an insurance company and a home builder over a subdivision project gone wrong. The owner, according to the court, “impliedly warrants the adequacy of the plans it supplies and which it requires its contractor to follow.”

But, as it turns out, the Texas Supreme Court was not done with Lonergan, not by a long shot.

The majority in the split decision in the appeal of El Paso v. MasTec, reached in 2012, relied on Lonergan in interpreting the messy details of the case. While El Paso, the project owner, had pledged to identify all foreign crossings, MasTec had also agreed to “fully acquaint itself” with the site. In the contract, the court ruled, MasTec “assumed full and complete responsibility for any such conditions pertaining to the Work, the site of the Work or its surroundings and all risks.”

The court ruled that while El Paso had agreed to review the site before the project began, the survey and mapping of crossings were a “joint effort” with MasTec and that El Paso’s obligation did not limit MasTec’s liability. Therefore, MasTec was ultimately responsible for the risk.

One Texas construction attorney described the Lonergan precedent as “a zombie” decision that rose from the dead.

Fred Heldenfels IV, head of precast concrete contractor Heldenfels Enterprises in San Marcos, Texas, says he has seen the impact of Lonergan firsthand. He cites a general contractor he worked with on a school project who is now being sued for alleged design defects on a middle school foundation. Some Texas law firms have created a cottage industry by teaming up with school districts and filing lawsuits against contractors and subcontractors, alleging construction defects or, in cases like the one above, design defects, Heldenfels claims. “To the contracting community, it seems like common sense,” Heldenfels said. “Whoever is responsible for the designs should be responsible for the design defects. The school board provides plans and specs to the contractors.”

Unfair Leverage

Lonergan gives project owners unfair leverage in dealing with contractors, says Raymond A. Risk, Jr., chief executive of the Texas Construction Association, which lobbies on behalf of the state’s subcontractors and suppliers. While designers are adept at limiting their liability to the loss of their fee, contractors can’t rely on their liability insurance to cover design defects for designs the contractor did not prepare. “The sophisticated owners who know what they are doing can put a lot of pressure on the contractor to fix defects, even though the defect was not caused by the contractor,” Risk said. “It gives them tremendous leverage. The owner now has two pockets to go after when a defect is caused by a design error. We believe there is a gross inequity for the construction team to be responsible for someone else’s design product.”

Still, Texas contractors have developed ways to deal with the potential disadvantage created by Lonergan, says attorney Amy Wolfshohl, by negotiating up front with project owners about the costs of design errors. “People are surprised if we don’t allocate the responsibility to the owner or design professional,” she says. Neal Sweeney, an Atlanta attorney, says contractors should be aware by now of the “front-end risk,” much in the same way they would be aware of adverse contract language. But most cases never get to court and are settled. “Net-net, in my view, it’s an important distinction without a difference.”

Whether or not that’s true, the premise underlying Lonergan is important with public contracts where there is little or no free-market bargaining over terms, especially if the contract doesn’t state who bears the risks for design errors.

Attorney Calvin Cowan wrote in a 2014 blog post that another, seemingly unrelated case added to the Lonergan risks in government work.

Cowan cited the decision that year in which the Texas Supreme Court overturned a damage award won by Martin K. Eby Construction Co. from the design engineer on a Dallas Area Rapid Transportation Authority project. The case involved design errors that led to cost overruns of millions. Eby sued and won a settlement from DART; remedies for design errors were outlined in Eby’s contract with DART. And Eby won $2.25 million in its lawsuit against the design engineer. But the state supreme court reversed the decision, noting that Eby had no contract with the engineer, and therefore could not claim negligence.

The Texas Construction Association and other industry groups are hoping to put a statutory stake in the heart of Lonergan this spring in the Texas Legislature. Everything must be done during a short four-month legislative session that concludes in May.

A bill that would have shifted liability for design defects over to project owners, architects and engineers made it out of the state house last year only to die in the state senate. A last-minute push by energy and chemical industry associations derailed the proposal. They argued that the measure conflicts with 100 years of Texas jurisprudence that believes a contractor’s expertise includes analyzing designs. The companies argued that the measure would have shielded responsible parties from accountability, shifted risk to property owners, disrupted freedom of contract and was merely an attempt to overrule Lonergan, which “appropriately assigns proportional responsibility based on the problem discovered in the project.”

The Construction Law Journal authors are making their case to the state’s legal community and to the Texas judiciary, which has the power to reinterpret Lonergan in ways that eradicate its influence in future cases. The authors wrote that change is likely and that the 1907 precedent, for all the reasons cited in their article, “is on unstable ground.”