Cedar Rapids Learns from Past Floods to Protect City

The 2008 flood left both banks of the Cedar River inundated with 31 ft of water.

COURTESY OF SASAKI ASSOCIATES

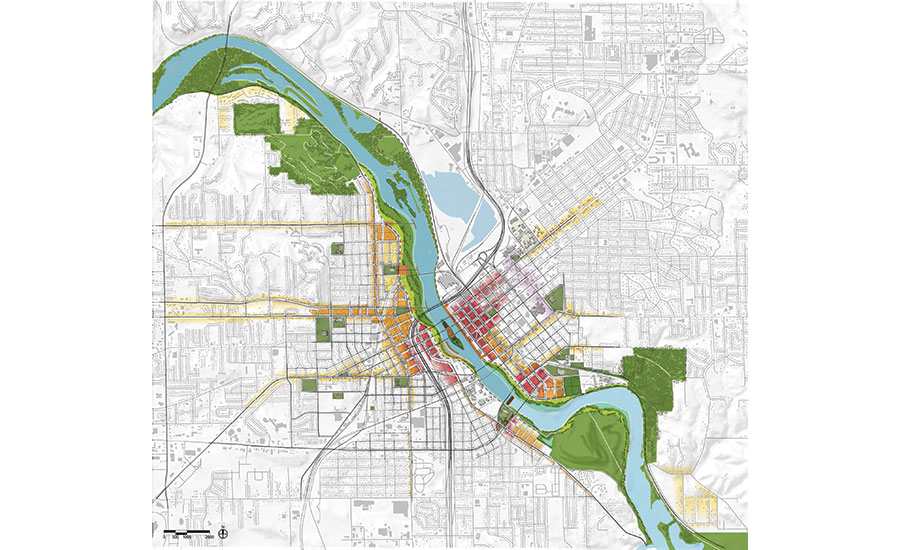

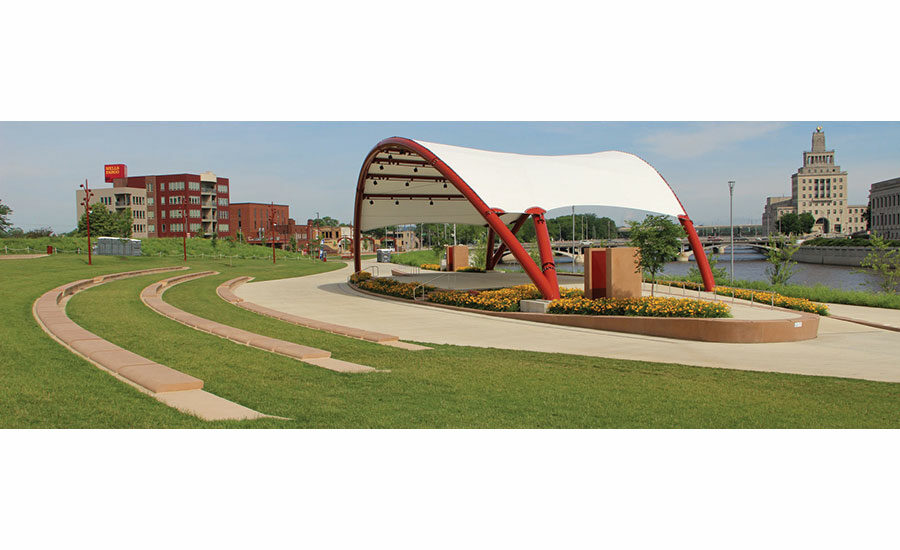

The plan to strengthen Cedar Rapids included buying property in low-lying areas and creating greenspaces and public amenities such as the McGrath Amphitheatre, which acts as a levy in high-water events.

PLAN COURTESY OF SASAKI ASSOCIATES

The plan to strengthen Cedar Rapids included buying property in low-lying areas and creating greenspaces and public amenities such as the McGrath Amphitheatre, which acts as a levy in high-water events.

COURTESY OF CITY OF CEDAR RAPIDS

HESCO barriers were effectively used to prevent flooding in 2016.

PHOTO COURTESY OF CITY OF CEDAR RAPIDS

As flood waters inundated neighboring communities and states last month, the residents of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, took some comfort in the barriers and measures put in place following the devastating floods of 2008 that would help protect them as waters surged. In March, the Cedar River rose to 18.1 ft, 6 ft above flood level, but nowhere near 2008’s record 31.12 crest. Since walls and levees are still being built, this year’s rising water required temporary barriers in the city to augment levees and pumps that have been installed since 2008. The biggest difference, however, was that the city was prepared.

As flood waters inundated neighboring communities and states last month, the residents of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, took some comfort in the barriers and measures put in place following the devastating floods of 2008 that would help protect them as waters surged. In March, the Cedar River rose to 18.1 ft, 6 ft above flood level, but nowhere near 2008’s record 31.12 crest. Since walls and levees are still being built, this year’s rising water required temporary barriers in the city to augment levees and pumps that have been installed since 2008. The biggest difference, however, was that the city was prepared.

“We had a scare, but we learned a tremendous amount since the 2008 floods, so we made physical investments, things such as levees and pumps and, in some areas, a flood wall” says Jeffrey Pomeranz, the city manager of Cedar Rapids. “We’ve also become much more educated on how to protect ourselves.”

Just as they did in 2016 when the river rose to 21.6 ft, emergency personnel put up temporary flood protections in March, including stackable HESCO sand-filled, wire-mesh and impermeable fabric barriers in low-lying areas to augment permanent protection, which includes new high-power pumps, stronger levees, and a flood wall along the east side of the river. Even as Cedar Rapids was flooding in 2008, Boston-based planning firm Sasaki was pitching a master plan to make the city more resilient. Two of Sasaki’s landscape architects were in Cedar Rapids when the 2008 flood hit.

Cedar Rapids’ two-fold approach to resilience involves strengthening at-risk areas while also integrating greenspace created by a post-2008 home- and business-buying program. The system will eventually include 7 miles of levees and flood plain along both the east and west banks of the Cedar River through downtown. The overall cost for the levees and land buyouts is estimated to be between $550 million and $750 million, depending on how quickly they are completed.

Some of the master plan, including the land buyback program and addition of greenspace along both sides of the river, has already been completed, but the modifications to Iowa’s second-largest city are ongoing.

The city is currently focused on improving its east bank. In June, Cedar Rapids was awarded $76 million in grants and $41 million as an optional low-interest loan through a federal emergency supplemental appropriation for flood protection measure. The Army Corps of Engineers also committed $117 million for river infrastructure improvements.

A $14.2-million floodwall near the Quaker Oats Campus and more pumps in the New Bohemia neighborhood helped in the most recent flooding event. HDR, Stanley Consultants and Anderson Bogert worked on the New Bohemia improvements.

More than 1,400 of the properties damaged by the 2008 flood were bought out by the city with money from a Department of Housing and Urban Development Community Development block grant. Cedar Rapids paid $93.9 million to acquire the land between 2008 and 2010: $58.1 million for residential properties and $35.8 million for businesses. The payouts were 107% of the pre-flood assessed value of those properties. Even the flood-damaged National Czech and Slovak Museum and Library was moved to higher ground.

“I’ve been here almost 10 years. When I first got to Cedar Rapids every week there was a big cart of documents that I had to sign from all the acquisitions we were making. It was a lot of work by lots of people to get to that point,” says Pomeranz, who is Cedar Rapids’ first city manager and was charged with modernizing flood protection and response upon taking the job.

That purchased land is now greenspace, levees and resilient parks.

“We did a comprehensive system plan,” says Laura Marett, senior associate in Sasaki’s landscape practice. “Because the flood protection plan had more or less identified 220 acres of new flood plain greenspaces, the idea is that there’s this floodable ecological corridor that is also layered with programs and amenities that benefit everyone. I don’t think there was ever a desire to turn away from the river; it’s such a core of the community.”

One feature is the McGrath Amphitheatre on the west side of the river. Completed in 2013, the live music venue functions as a levee in a flood event and is within a park designed with materials and plantings intended to withstand flooding.

“It’s really meant to be a community amenity most days of the year, when there’s no flooding happening,” Marett says.

Sasaki’s master plan promises the ability to withstand volumes greater than the record-setting 2008 flood, but that’s dependent on several stakeholders implementing the entire plan on both sides of the river. The Cedar Rapids City Council raised property taxes last year to pay for $264 million of the improvements.

Cedar Rapids will spend $20 million on resilience projects this year, which are mainly on the east bank. That amount will increase to an estimated $35 million to $40 million in 2020 and then to at least $50 million in 2021 and 2022.

“We worked with the city, and the community, and a lot of stakeholders at the Army Corps of Engineers, to plan a series of system-level plans,” Marett says. “So we looked at the alignment of the flood protection throughout the whole system.”

The Army Corps of Engineers’ Rock Island District manages the river and plans to award contracts for levees, floodwalls and bridges in Cedar Rapids this year.

Cedar Rapids still sits at the bottom of a 5-million-acre watershed that begins in Minnesota. The master flood control plan is being implemented as quickly as Cedar Rapids, the Army Corps and other stakeholders can land funding. While most of the east bank is now either completed or close to construction, some west bank plans are still not funded.

“You’ve got to have a plan in place from the very beginning and then execute on that plan,” Pomeranz says. “While difficult for the community, we’ve really come back better and stronger, from what was the worst … disaster in Cedar Rapids history.”

When Sasaki held community meetings about how to rebuild after the 2008 flood, they offered an option of simply rebuilding both banks with higher walls. Residents didn’t land on a straight rebuild and agreed to trade-offs.

“When we’re doing the flood management strategy process with the community, we put out extreme ideas to tease out people’s interest such as, ‘What if you retreated all the way from the 500 yard flood plain?’ and ‘What if you built walls right up to the river?’ They didn’t want exactly the same with higher walls. They really wanted to rebuild in a more resilient way, that would [also] create this room for the river,” Marett says.