Structural Failures

Spreading Cracks On FIU Bridge Failed to Alarm Project Team

On the morning of last year’s Florida International University pedestrian bridge collapse, when the engineer of record assured project team members that there were no safety risks related to cracks propagating across a part of the unusual single-truss structure, other project team members voiced mild concern, but no alarm.

In hindsight, considering that the bridge had no inherent structural redundancy as it sat, incomplete, straddling a busy highway—and would suffer a sudden, catastrophic and deadly collapse just hours later—the team’s lack of urgency remains puzzling, say engineering experts contacted by ENR for comment.

“Do we need temporary shoring?”

– FIU bridge inspection company at meeting hours before the March 15, 2018 collapse

Minutes of the meeting in the contractor’s field office recently released by the Florida Dept. of Transportation show that attendees offered modest suggestions and questions to FIGG Bridge Engineers.

Bolton Perez & Associates, the project’s construction engineering and inspection contractor, asked, “Do we need temporary shoring?,” for instance. FIGG officials responded that it was not necessary. Instead, the minutes show that FIGG staff suggested that steel channels and post-tension bars would “capture some of that force which is better than vertical support. The diagonal member is what needs to be captured.” To the suggestion that another engineer should peer review the bridge’s cracks, FIGG concurred.

An official with FIU asked a representative with Bolton Perez their opinion of FIGG’s presentation analysis. Bolton, Perez said they could not comment at the moment, but would “expedite” a response in 2-3 days, according to the notes.

An FDOT representative asked FIGG to supply a copy of the presentation for the agency’s records.

Puzzled by Cracks

Engineers asked by ENR to review the meeting presentation and minutes for this story don’t believe that it shows exactly what errors or mistakes precipitated the sudden collapse.

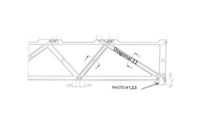

Designed with a single central, open truss, the pedestrian bridge structure featured a narrower top chord. The top chord was to serve as a canopy over the wider bottom chord, which would be the walking surface. Cables from a 109-ft-high central pylon, not yet built at the time of the collapse, would add stability, according to the design-build proposal. The concrete deck was designed with two-way post-tensioning tendons.

At the time of the collapse, contractors were apparently adjusting a tension rod in one of the diagonal struts between the chords at one end of the bridge. It is possible that the project’s prime contractor, MCM, and its post-tensioning subcontractor, in attempting to fix the problems, made an error that caused the bridge’s single truss to crack and give way. According to the National Transportation Safety Board, crews reportedly had been re-tensioning diagonal member 11 at the time of the collapse. Lacking redundancy, the truss failed at that end and fell to the ground, smashing autos and claiming six lives.

Just days before the meeting, the truss structure cast alongside the road was loaded onto its permanent supports and inspections showed no distressed members. But two days before the collapse, MCM emailed FIGG about cracks. FIGG responded by instructing MCM to install temporary shims in the base of a pylon directly below the portion of the bridge with the cracks, between the permanent support shims.

Then, on March 15, 2018, engineers, contractors, consultants, state DOT representatives and officials with FIU, the project owner, gathered to hear why the bridge designer thought cracks were occurring around part of the structure’s walking surface. The section in question was the bottom chord of the concrete truss comprising the bridge, at one of the diagonal web members at the structure’s north end.

Meeting notes indicate that it was known that cracks were “growing daily.”

Despite that, FIGG Bridge Engineers assured project team members that they saw “no safety concern” due to the cracking. According to the meeting notes, FIGG’s lead technical designer Denney Pate—who led the presentation, according to FIU—and bridge engineer Eddy Leon were on site for the presentation. Dwight Dempsey, FIGG’s design manager, joined by phone.

Team members in attendance probably held Pate’s opinion in high regard that morning. FIGG-MCM’s design-build proposal lists numerous accolades for Pate in support of its description of him as “one of the leading bridge designers in the world.”

A slide from FIGG’s presentation summarized the firm’s conclusion: “After about an hour of review and evaluation, FIGG had conducted sufficient supplemental/independent computations to conclude that there is not any concern with safety of the span suspended over the road.”

Responding to ENR’s request for comment, the Tallahassee, Fla.-based engineering firm would not elaborate on the above quote, instead stating: “The most important thing is to arrive at the truth. The complex investigative analysis of the construction accident is ongoing. It is inappropriate to speculate on potential outcomes with limited available information. The NTSB process precludes us from comment on investigative information until the NTSB process is complete.”

Failure to Protect Public Safety

In retrospect, the reviewing engineers all wonder why concerns raised by Bolton Perez didn’t trigger alarm, and why no one on the project team insisted the busy road beneath the partly complete bridge be shut down.

Richard Rice, a certified forensic engineer and president with Mutual Engineering, Hampton, Ga, said that he’s “been in that meeting” discussing mysterious cracking, citing his involvement with the shutdown of a parking garage at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in the late 1980s, over what turned out to be minor surface cracking in some precast double-tees.

The firm he was working for at the time stopped work “because we had a duty to protect life and property.” By comparison, the cracks occurring on the FIU bridge “were astonishing” in size, Rice says.

William L. Gamble, professor emeritus of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Illinois in Urbana, told ENR that he was “dumbfounded, greatly surprised and appalled” at the documents detailing the meeting, adding: “Yes, reinforced concrete structures often crack, but no, the cracks should not be large and growing day by day.

“I still find it hard to believe that anyone who had taken, and passed, a course on reinforced concrete design and behavior could not be greatly concerned,” he added. “Cracks that one can stick the end of a tape measure into are a collapse waiting to happen.”

Martin E. Gordon, a forensic engineer and professor in the Rochester Institute of Technology's College of Engineering Technology, says speculation about what happened can be dangerously misleading and any conclusions should await the publication of detailed analysis by forensic engineers.

Gordon, however, adds that he is interested in why the design and construction team didn't shut the road beneath the bridge. “It would still be important to review the details of what caused them to make that decision, but on a personal basis I don’t understand why they didn’t isolate that bridge.”

Unusual Design

Rice, the Georgia forensic engineer, remains most perplexed over the designer’s use of a single truss. “That just blew me away,” he says. “To have a single truss like that is violating one of the first tenants of structural engineering—provide redundancy. If you're going to make a truss bridge, you have at least two trusses,” he argues.

In November, the NTSB issued an investigative update stating that "errors were made in the design of the 174-foot span and cracking observed prior to the collapse is consistent with those errors."

The update stated: "Errors made were in the design of the northernmost nodal region of the span where two truss members were connected to the bridge deck. The design errors resulted in an overestimation of the capacity (resistance) of a critical section through the node, and, an apparent underestimation of the demand (load) on that section." The Federal Highway Administration’s Office of Bridges and Structures conducted the design review on behalf of the NTSB’s investigation.

The NTSB says major investigations such as this one normally take 18-24 months to complete, which would mean later this year or early 2020 before its findings are made public.

The Occupational Safety & Health Administration, meanwhile, has completed its investigation into the causes behind the collapse, sources say, but is waiting to release its findings until the NTSB completes its work.