Bullitt Center's Hayes Shares Rain-to-Tap Water-System Saga

Bullitt Center’s on-site rain-to-potable water treatment system, pushed by Hayes, was approved for operation 51⁄2 years after the office building opened in 2013.

Photo by Brad Kahn

Herndon spends four mornings a week making and testing the drinking water for the building’s 175 occupants.

PHOTO BY BRAD KAHN

Herndon spends four mornings a week making and testing the drinking water for the building’s 175 occupants.

Photo by Brad Kahn

Bullitt recently added a second holding tank (at right, above) to increase capacity and keep the system running smoothly.

PHOTO BY DYLAN HERNDON

Dylan Herndon spends about three hours several mornings a week in a windowless basement room in Seattle’s 52,000-sq-ft Bullitt Center—likely the world’s most sustainable speculative office building. There, he concocts the specialty of the house—drinking water made exclusively from captured rainfall.

Bullitt’s potable-water treatment plant is the heart of the Bullitt water district. As the highest-capacity single-building rain-to-tap system, the district is “unlike any other,” says Herndon, a certified water treatment specialist for Water & Wastewater Services. W&WS, which manages 200 water and wastewater utilities in Western Washington, has a service contract with Bullitt’s building manager, Unico Properties.

Herndon was the first one to sip Bullitt’s water. “I have been very surprised at the consistency of the raw water quality and how easy it has been to treat,” he says.

Bullitt is groundbreaking. No other spec office building is a water district. No other water district is six stories, complete with roof rainfall catchment and a vertical, rather than a horizontal, distribution system.

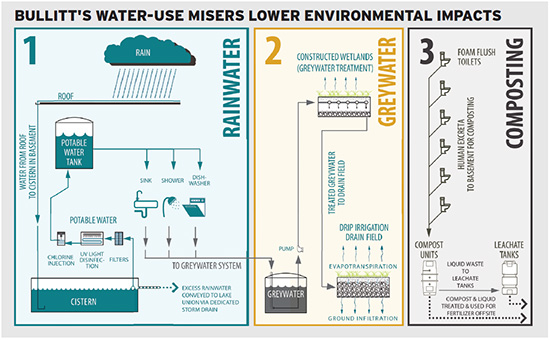

Source: Integrated Design Lab, University of Washington

Herndon has been serving his beverage to Bullitt’s 175 regular occupants since 3 p.m. on Nov. 1. The moment, which arrived 51⁄2 long years after the building opened in 2013, was cause for celebration, especially for Denis Hayes, president of Bullitt’s owner-developer-occupier—the Bullitt Foundation. Hayes is the mastermind of Bullitt’s living laboratory, developed to demonstrate the viability of sustainable buildings (ENR 2/7/14 p. 28).

Hayes attributes the protracted and arduous approval time for Bullitt’s water system to inexperience—and offers lessons learned to others. Bullitt’s cautionary tale has already aided five on-site water projects, including one for the 50,200-sq-ft Santa Monica General Services Building, on course for completion next April.

For one of Bullitt’s seven tenants—the International Living Future Institute—Nov. 1 was also a watershed day. ILFI is the steward of the world’s most demanding sustainable-building certification program, called the Living Building Challenge. Jason McLennan, ILFI’s chairman, received ENR’s 2016 Award of Excellence for creating the LBC (ENR 4/11/16 p. 42).

Bullitt Center, the first, largest and tallest office building to achieve full LBC certification, is ILFI’s poster Living Building (LB). Certified in 2015, Bullitt is “critical to us,” says Amanda Sturgeon, ILFI’s CEO. “It was the first building to get us beyond environmental centers and into the urban context.”

Bullitt’s water saga—and the outright rejection by regulators elsewhere of other rain-to-tap systems—has altered ILFI’s mind-set. “Water, not materials, is now the biggest challenge,” says Sturgeon. Teams have been dropping out of the LB program because the water imperative takes too much, often fruitless, effort, she adds.

In response, ILFI has revamped its water rules to focus more on conservation. And for an LB, though a team must design a rain-to-tap system and try to get it permitted, construction is no longer required.

Most Challenging

Hayes agrees that implementing Bullitt’s water system was the most challenging part of a very demanding development. “Public health officials take safe drinking water very seriously, as they should,” he says.

One obstacle was the absence of a clear path to create a “new public water system in the middle of an existing public water system” that already has adequate supply and conforms to regulations, says Steve Deem, regional engineer in the office of drinking water of the Washington State Dept. of Health. WSDOH is the regulatory body for the Bullitt water district.

Under state regulations, Bullitt is considered a Group A nontransient, noncommunity system, with surface catchment, because it serves more than 25 people in a nonresidential setting who use the building for more than 180 days each year. The system is tied into the city water system, in case of a disruption in service, and has a city fire-sprinkler connection. For Bullitt’s first 5½ years, it drew city water for potable uses. The on-site potable water system was used for nonpotable needs.

About two years before the building’s groundbreaking, Bullitt’s team met with WSDOH and, according to Deem, was given requirements for filtration, disinfection and monitoring and reporting for a Group A water district. Instead, the team filed for approval after construction of a fully equipped water treatment plant with rainwater catchment on the roof of a house, says Deem.

Hayes takes the blame. He advises owners and developers of rain-to-tap water systems to engage a qualified and experienced water system engineer from the outset. The engineer must have knowledge of the system type, the regulatory environment and the approvals process—at city and state levels. He also cautions against design, procurement and construction until regulators grant conditional approval.

“Bullitt Center is critical to us. It was the first building to get us beyond environmental centers and into the urban context.”

– Amanda Sturgeon, CEO, International Living Future Institute

To help revamp the Bullitt system to conform to regulations and shepherd it through approvals, the Bullitt Foundation engaged water-systems engineer Gray & Osborne Inc. The redesign of the treatment system from residential to commercial was “fairly simple,” says Russ Porter, a G&O principal.

Still, there were headaches. Hayes’ resistance to trace amounts of chlorine disinfection—required to prevent bacterial growth, especially if introduced at the tap or showerhead—was a huge obstacle for approval.

“The belief that chlorine disinfection is evil was their biggest hang-up,” says Deem. “Trying to get around that requirement wasted two years.”

During that time, Hayes contacted local, state and federal officials to get an exception, all the way to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency administrator. “After significant exploration, we learned that chlorine is a statutory requirement,” he says.

In hindsight, Hayes admits his quest to avoid chlorine disinfection was quixotic. It “took significant time, frayed relationships with regulators, was unwise on its merits and stood no chance of success,” he says.

There is a workaround to keep chlorinated water from ingestion—charcoal filters at taps and showerheads. Bullitt doesn’t have filters, but the LBC, in its latest version, allows chlorine disinfection if there are filters.

Other nonconforming items were a bit easier to eliminate. Washington state requires any surface in contact with rainwater, before it reaches the cistern, to be certified by the National Sanitation Foundation or tested to NSF standards. The objective is to ensure no harmful chemicals leach into the rainwater supply.

The original system’s membrane filters were not NSF certified and were removed. The bigger hiccup was that the SunPower rooftop solar array and the roof catchment-area surface were not certified or tested.

Hayes persuaded SunPower to underwrite the certification, which cost about $35,000. But it took nearly two years to find a testing location and to test panels.

If every type of module produced by the dozens of manufacturers selling solar equipment in the U.S. needs to be individually approved, “the delays and transaction costs will be crippling,” Hayes says.

The roofing material problem was easier to fix. At the time, with no membranes NSF-certified, crews applied an NSF-certified coating on top of the original membrane. Currently, there are several coatings available and at least two NSF-certified membranes.

To minimize the need for surface certification, Bullitt advises keeping equipment off the roof. If that is not possible, designers should direct drainage from air handling equipment away from the catchment area. Foot traffic for maintenance should also be minimized.

Creating an on-site rain-to-tap water system does not pencil out. Bullitt’s plant cost approximately $175,000. The W&WS operating contract costs about $3,000 per month, which includes operating insurance.

According to Bullitt, the average potable water use in Seattle commercial buildings is about 20 gallons per sq ft per year. Bullitt used an average of 1,237 gallons each week since Nov. 1. That translates to about 1.24 gallons per sq ft per year, or about 93.8% less water use than the average Seattle building.

Projected lower utility costs from Bullitt’s systems, including composting and greywater recycling, are based on the cost of city water. Unico estimates city water costs at $0.38 per sq ft. Bullitt budgeted $0.03 per sq ft, which means utility bills that are about $17,500 lower per year.

Hayes maintains the water-system cost should be justified by expectations of future conditions. “In many parts of the U.S., water rates are likely to rise as climate change impacts the hydrological cycle,” says Hayes in the foundation’s 115-page report on the water system. Neighborhood, rather than single-building water districts, might make more economic sense, he says.

WSDOH did not grant Bullitt’s approval-in-concept for potable water uses—taps, showers and dishwashers—until the fall of 2017. That was 4½ years after the building opened. To get final approval, G&O had to do a pilot study to prove the water system could meet all water quality regulations while operating. During the March 2018 to September 2018 pilot, treated rainfall was used for nonpotable purposes only.

The system has a 46,200-gallon raw-water buried cistern. There is a 5-micron point-of-use residential cartridge filter and two 0.5-micron cartridge filters in series. Other components include an ultraviolet disinfection device, a calcite contactor that adds alkalinity and adjusts pH and sodium hypochlorite disinfection.

Primary disinfection occurs in dedicated contact piping totaling 227 gallons. Treated water is stored in two, connected 500-gallon day tanks. G&O added the second tank recently, mostly to meet unanticipated demand. The distribution system consists of the original code-compliant plumbing.

Eyes on the System

As the certified operator, W&WS’s Herndon is required to report operational data to WSDOH and to ensure treatment goals are met. If water quality issues arise, or demand is extremely high outside of his scheduled visits, Herndon comes in to run the system.

“We have eyes on all areas of the water system daily and at least semiannually we inspect the roof catchment system and the cistern,” he says.

WSDOH will conduct inspections every three years to identify any deficiencies in operations or facilities that may pose a risk to the system or to public health.

Herndon’s biggest surprise is how fast chlorine dissipates in the distribution system when water is not used for long periods. He remains on guard for that, he says.

The system has only been off line twice. Both times, the emergency intertie to city water took over.

The first time, a valve in one of the foaming systems in a composting toilet malfunctioned one evening and drew down the day tank below the alarm level. Building engineers repaired the leak and Herndon put the system back in service the following morning, once the day tank reached a usable level.

The system also was shut down to install the second day tank. The older tank was drawn down, isolated and moved to install the new tank.

Herndon’s typical sequence begins with calibrating the pH meter, colorimeter and turbidimeter and taking readings. Next, he collects residual chlorine from the sixth floor and at the basement entry point. He then starts the system by activating control switches for the tank-fill solenoid, UV disinfection module and the cistern pump, and starts the hypochlorite injection pump.

Next, Herndon checks for proper operation and flow rate. Following this, he takes initial chlorine/pH/temp/turbidity samples. More samples follow and chemical adjustments are made during the fill cycle. At the end of the cycle, Herndon collects even more samples. Once the tank is full, he manually turns off the system.

Even with the Bullitt system running well, WSDOH’s Deem has qualms about on-site water production. One is the supply reliability of a rainfall-only system. “We have dry summers,” he says. “Quality degrades when water is stored [in a cistern] for five months.”

Further, a roof can collect contaminants, degrading the quality of the supply water. And for health reasons, the system has to work all the time. “Even a 10-minute break can introduce microbes,” Deem says.

“The Bullitt Foundation had already saved the planet with the composting toilets,” which account for 50% to 60% of the building’s water demand, he adds.

“There is lots of cost for the last bit of water and it may not be better than city water,” Deem says. “We are all on board for saving the planet, we just think [decentralization] should make sense,” in terms of reliability, water quality and public health.