Project Delivery

Despite Feds' Raised Bar, $2.8B Massachusetts Offshore Wind Project Presses On

New U.S. Interior Dept. demands will delay construction of Massachusetts’ 800-MW Vineyard Wind.

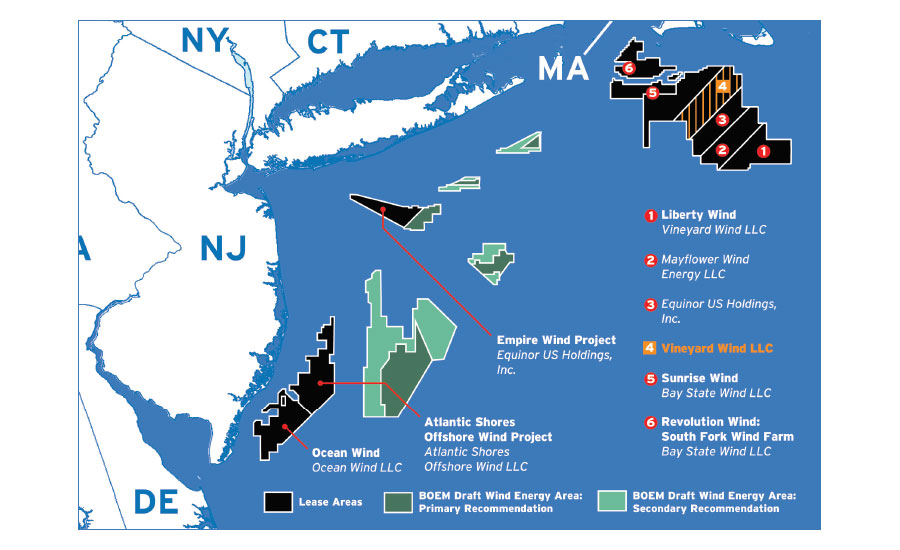

MAP: BOEM

Developers of the 800-MW, 84-turbine Vineyard Wind offshore wind energy farm in Massachusetts, set to be the first and largest commercial-scale project in the U.S., say they are committed to pushing through its $2.8-billion construction despite a sudden Trump administration permitting setback.

The project, originally set to gain a key final environmental permit in June so construction could start by year-end, allowing use of a soon-to-expire renewable energy federal tax credit, now must vastly expand study of potential impacts to commercial fishing—including those of other pending projects—before work can start, based on new U.S. Interior Dept. mandates.

DOI’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which leads the federal inter-agency review, on Aug. 9, told the developer—a joint venture of Copenhagen Investment Partners and Avengrid Renewables—that it had to expand its analysis of Vineyard Wind to take into account the cumulative effects of other offshore wind projects that have been awarded power purchase agreements as well as state procurements of offshore wind generation that are expected to be awarded. (see map).

DOI wants reference to a larger buildout of offshore wind capacity than was analyzed, based on new stakeholder concerns voiced.

Annie Hawkins, executive director of the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, a new fisheries industry advocacy group, argues that analyzing effects of one wind farm is insufficient. “There are 1,400 square miles of leased areas in one New England cluster,” she says.

But expecting one project to carry the cumulative impacts of others that may or may not be built is too big a burden, says Tim Charters, vice president of the National Ocean Industries Association, a trade group that represents U.S. offshore energy, oil and gas and marine sectors.

Offshore wind observers say the U.S. position change stems from new Interior Secretary David Bernhardt, confirmed in April, who has not indicated the same support for offshore wind as his predecessor Ryan Zinke.

DOI did not respond to a request for comment.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Marine Fisheries Service—within the U.S. Commerce Dept.—said it does not concur with BOEM's decisions related to distance between its 84 planned turbines and their alignment because of claimed hazard to commercial fishing, said Michael Pentony, NOAA’s regional administrator.

The turbines are set to be spaced 0.75 nautical miles apart and aligned in a northwest-southeast orientation. NOAA wants them spaced one-mile apart and aligned in an east-west direction “to minimize impacts to fishing operations.”

Lobbyists for the commercial fishing industry sought a more comprehensive study that would show how the buildout of various proposed wind farms in the region would affect that sector's operations.

“We are disappointed not to deliver the project on the timeline we had anticipated,” Lars Pedersen, CEO of Vineyard Wind said in a statement.

There are other repercussions to a delay in construction, including pressure on the multitude of tier one and tier two suppliers that are committed to the project.

Vineyard said more than 50 design, construction and other companies have either been awarded project development contracts or are bidding on them.

Liz Burdock, CEO of trade group Business Network for Offshore Wind, is concerned about slowdown in the offshore winh sector's growth momentum. “We’re on the cusp of hiring 10,000 workers and we don’t want to pause that,” she says.

Vineyard has not received any specific requirements for the expanded analysis from BOEM, but the company said the timing of such a study could not be completed within its timeline to begin construction before 2020.

BOEM had initially pushed back against the NOAA mandate, saying it had weighed how to avoid impacts. It also said NOAA’s request would disqualify Vineyard Wind from an expected 24% federal tax credit that expires Dec. 31 and factors in its financial framework and ability to deliver power to Massachusetts utilities at an already set price that is significantly less than what residents now pay.

“BOEM would be approving a project with very little likelihood of eventual construction,” said its chief environmental officer, William Brown in a letter to NOAA. The agency held that position for months until it recently informed the project of the changed environmental study parameters.

Three bills now are pending in Congress to extend the tax credit for from five to eight years, with some observers speculating that the extension could be included in tax extenders legislatlon that passed the House Ways and Means Committee but whose passage this year depends on an uncertain level of bipartisan cooperation.

BOEM has until March to approve the multiagency review but could take months longer to grant the final permit.

Burdock says Vineyard Wind may still gain the tax credit since BOEM caused its delay.

Meanwhile, Massachusetts’ congressional Democrats and three Louisiana Republicans, in an Aug. 16 letter, urged the U.S. agencies to “mitigate any additional delay that may threaten the overall project.”