Construction Disputes

WWII Museum Hotel Project Team Hopes to Avoid Claims Trial

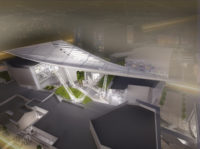

A lawsuit targeting the engineer on the National World War II Museum’s Higgins Hotel & Conference Center alleges that some of the steel beams were undersized and insufficient to bear the loads of the eight-story building. The original steel structure is shown here prior to repairs.

PHOTO COURTESY PALMISANO LLC

A nonprofit representing the National World War II Museum is working toward a settlement but preparing for a jury trial in its lawsuit against the structural engineer of its $65-million hotel and conference center, under construction in downtown New Orleans. The lawsuit, targeting DeSimone Consulting Engineering Group, alleges that the engineer is responsible for structural steel design errors that resulted in two months of project delays and more than $1 million in damages.

The timing of the response to the purported problems with the steel is a big issue in the claims by the museum and contractor. And now the prospect of a possible settlement looms large. A federal court has ordered the parties to hold their first pretrial telephone conference Sept. 26 if no settlement is reached.

The disputants on a late-running project seek a settlement on repair costs

As far as construction disputes go, the issues are conventional. Even the length of the delayed completion and the amounts of money in dispute are modest compared to other, more spectacular disputed claims. But the conflict is typical of the type of disagreements that continue to plague construction on a routine basis and which spill into the courts regularly. Now, a fairly high-profile project at an important cultural institution is spilling into public view.

The 230-room Higgins Hotel & Conference Center is part of a $400-million expansion underway at the museum. Also under construction are the $25-million, 34,800-sq-ft Hall of Democracy pavilion and the $14-million, 150-ft-tall Bollinger Canopy of Peace structure. Both projects are scheduled for completion this year. The Liberation Pavilion, focusing on end-of-war and postwar experiences, is the final planned exhibit space. The lawsuit involves the hotel and conference center.

Representatives of both the museum and the lead contractor, Palmisano LLC, say the hotel’s structural integrity has been fully restored and that the hotel is on track to open later this year, but only after Palmisano and its subcontractors performed extensive repairs on numerous beams, columns and the foundation.

“The hotel is scheduled to open later this year, and it has not impacted any other construction projects on the museum’s campus,” a museum spokeswoman said in a statement.

Moved to Federal Court

The lawsuit, originally filed in April in state court, has been moved to federal court in New Orleans. World War II Theatre Inc., the museum’s nonprofit arm building the hotel is the plaintiff. In addition to DeSimone, a New York City-based engineering practice with offices in several other cities, the lawsuit names as defendants two insurers.

Unlike some other, more contentious construction delay lawsuits, the key parties, which had never worked together before, have remained on speaking terms.

Shannon Holtzman, the plaintiff’s attorney who represents the museum on various matters, said her client has been engaged with the other side since December—including a daylong mediation in May. She says the museum has maintained an ongoing dialogue with the engineer in hopes of avoiding the expense and extra work of discovery, depositions, experts and other steps involved in a jury trial.

“We remain hopeful that we can settle, but we won’t settle unless reasonable terms can be reached. But we’re not there yet,” she says. “If we’re not able to settle fairly soon, we’re fully prepared to litigate the case.”

The suit claims that some of the steel beams DeSimone designed were undersized and insufficient to bear the loads of the eight-story building, and that structural design issues resulted in at least a 61-day delay to the completion of the project. The hotel is nearly finished, and Palmisano is scheduled to turn over the project to the museum by late September.

Attorneys representing DeSimone did not respond to requests for comment. And DeSimone officials declined to comment given the sensitive nature of the legal dispute and settlement negotiations. But the engineer’s reply to the complaint against it claims that the museum shares blame for the delays, repair and rework that have set back the project.

The only accounts of the design and construction trouble and how the events surrounding it unfolded comes from the museum’s lawsuit complaint, originally filed in state court, and interview comments from the prime contractor’s CEO, Wes Palmisano.

Sagging Noticed

The lawsuit states that in April 2018, Palmisano LLC notified the museum that some of the structural steel beams it installed on the second and third floors of the building’s east side appeared to be sagging following the installation of the steel deck. The suit claims that DeSimone confirmed that the beams, which it had designed, were undersized and insufficient to handle the building’s loads, and that remediation would be necessary. The assertion about what DeSimone confirmed could not be independently verified.

This led Palmisano to fabricate additional steel and reinforce five beams on the second floor. The contractor also removed six beams on the third floor and replaced them with larger beams.

In early August 2018, Palmisano notified the museum about new concerns regarding the building’s structural integrity. According to the complaint, Palmisano discovered that another steel beam, which it had installed on the third floor of the building’s east side, also appeared to be too small and was unable to support a concrete block wall load, extending from the third floor up to the ninth floor roof.

In mid-August, DeSimone ordered Palmisano to stop work on the concrete wall so it could address the issue, the complaint says. The lawsuit claims that DeSimone took no further action to review the design’s structural integrity, including the foundation, even though the engineer had issued the stop-work order. According to the lawsuit, the museum had to cover costs of $433,000 for Palmisano to keep working on the building.

On Aug. 30, project architect Nichols Brosch Wurst Wolfe and Associates Inc.—DeSimone’s designated representative on the project—notified the museum that DeSimone had discovered more than 27 locations with undersized beams. Third-party consultant Ysrael A. Seinuk P.C. confirmed this finding in its peer review report two months later.

As a result Palmisano claims it was unable to complete the roof and make the building watertight on time, further delaying the project schedule. The lawsuit also contends that following the discoveries of the various structural deficiencies, DeSimone did not act quickly enough to mitigate damages and prevent delays, work on the repair designs, or assign enough staff to resolve all the issues. Almost 12 weeks had passed, the lawsuit claims, before the engineer had finished final repair details on the initial third floor beam after the structural deficiencies were discovered.

Attorneys' Email Exchange

In the spring, a separate sequence of events played out over the timing and deadlines for filing of legal pleadings. Lawyers for both WWII Theatre and DeSimone exchanged emails agreeing that the deadline for DeSimone to respond to the basic lawsuit would begin a month after the May 17 mediation.

In the interim, the lawsuit was moved to federal court. Charles B. Long, DeSimone’s attorney, emailed Holtzman asking for an informal extension of time for DeSimone’s formal reply pleading to the basic lawsuit complaint until June 28. Holtzman declined the request in an email to Long. “Unfortunately, I do not have authority to grant any additional extensions as my client reasonably believes that it is being strung along. [The museum] has been promised an offer since January, it’s been more than a month since the mediation, and still no offer has been made.”

DeSimone did file on June 24 a reply to the basic lawsuit. In it, the engineer denied or denied for lack of sufficient knowledge most of the detailed allegations against the firm. One of the defenses that the engineer spelled out is that it did not breach the duty of care to perform its services and that the plaintiff’s own negligence bars or diminishes DeSimone’s liability.

By Autumn Cafiero Giusti, with Richard Korman