Editorial: The Unspoken Messages in NTSB's Miami Bridge Collapse Report

The last time the National Transportation Safety Board came down hard on engineering and construction was in 2007.

That year, the board delivered reports on the collapse of the I-35 Highway Bridge in Minneapolis that killed 13 people, and on a ceiling collapse in a Boston Central Artery tunnel that killed one motorist.

Both involved completed structures. With its final investigation findings, the board also made recommendations for new standards and procedures and quality control.

NTSB's report on last year’s Miami bridge collapse at Florida International University in mid-construction, which killed five motorists and one construction worker, has similar recommendations. But it also has stinging criticism of the structural engineer and of the performance of the construction team as a whole.

Of the many investigations the board has performed, chairman Robert Sumwalt pointed out, none has had as much finger-pointing.

Keeping the obligation to public safety front of mind might have helped overcome the false sense of security that obscured the unfolding disaster.

Magnum Construction Management and its subcontractor on a design-build contract, FIGG Bridge Engineers, each accuse the other of making the fatal errors.

Once cracks grew significant, one might assume that on this singular project and design there would be a cohesive and effective crisis response.

What happened instead was passivity and deference to engineer FIGG, which failed to recognize the emergency.

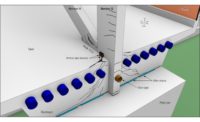

NTSB and other engineers claim that the one-of-a-kind structure was showing signs of distress in the days before the collapse. Present at the bridge the morning that it collapsed—and after viewing cracks deemed by NTSB to be 40 times larger than considered normal—FIGG nevertheless assured the rest of the team there was no hazard.

Under its contract, FIGG did not assume construction responsibility and was only required to make periodic visits to check the work for conformance with design.

But FIGG’s mystifying incaution as cracks spread remains puzzling—as does the failure of construction engineering and inspection firm Bolton, Perez & Associates, the Florida Dept. of Transportation and the university to intervene, each of which knew of the worsening cracks.

NTSB said each member of the team had an “implied authority” to shut the road to all traffic or require reshoring—not spelled out in contracts but as tangible as the tons of concrete above the passing motorists. None acted on that authority.

In the paper world of contracts, only contractors are responsible for means and methods.

In the real world, partly as a result of NTSB investigations and civil lawsuits—but unstated by the board—design engineers face expanding liability. They will always be the first ones consulted when it comes to protecting human life.

Few collect fees commensurate with that awesome liability. But recognizing how wide that responsibility stretches, and keeping the obligation to public safety front of mind, might have helped overcome the false sense of security and groupthink that obscured the unfolding disaster.