FIGG's Theory of Collapse Failed to Sway NTSB Team

In its Oct. 22 announcement of the probable cause of the Florida International University pedestrian bridge collapse, officials with the National Transportation Safety Board characterized the investigation as one of its most complex.

NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt, noting that he’s been on the safety board for 13 years and deliberated over nearly 200 accidents, said, “I don’t think I’ve ever seen one where there’s more finger-pointing between the parties. In fact, that is correct—because everyone shares a piece of this accident.”

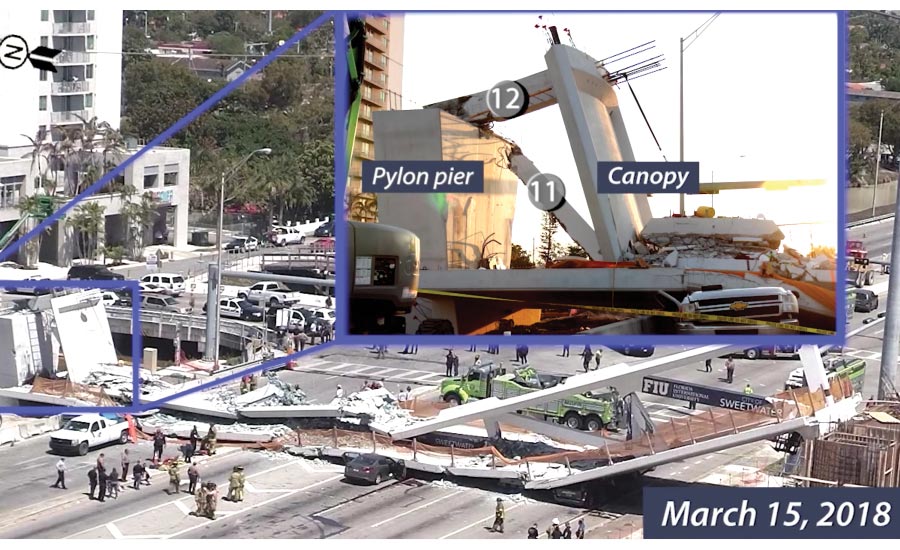

The agency’s list of 30 findings mentioned numerous project team members, including FIU, the Florida Dept. of Transportation, contractor MCM, Louis Berger Associates, and Bolton, Perez & Associates, for errors and missteps leading up to the March 15, 2018, tragedy that killed six people.

But it was FIGG Bridge Engineers that took the brunt of the criticism from the NTSB. In all, the federal safety agency specifically called out the Tallahassee, Fla.-based bridge design firm in more than a dozen of its findings.

The agency criticized the bridge designer for a host of alleged shortcomings, including: “poor judgment” in concluding the bridge was a redundant structure; producing inconsistent construction plans; utilizing incorrect factors in its calculations that led to “significant design errors in the determination of loads leading to a severe underestimation” of demands on certain portions of the structure; and not performing its due diligence relative to the project’s peer review, among numerous other items.

NTSB’s announcement of its interim report also made quick work of dismissing FIGG’s contention—submitted to the agency in September via a 344-page report—that the bridge collapsed primarily due to construction errors, specifically the intended roughening of cold joints.

FIGG based its opinion on an analysis performed by forensic engineers Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates (WJE) that claims the contractor’s failure to roughen key cold joints decreased the structure’s shear capacity in the region that collapsed by an estimated 78%.

While noting that the contractors failed to roughen the cold joints, the NTSB addressed this theory by stating: “Even if the cold joint surface of nodal region 11/12 had been roughened to a 0.25-inch amplitude, node 11/12 would not have had sufficient capacity to counteract the demand load for interface shear—and the bridge would still have been under-designed and could have failed.”

WJE’s conclusions from its testing of replicas of the bridge’s components and analysis of the collapsed structure differs from NTSB’s conclusion, stating: “The intentional roughening of the construction joint following FDOT Standard Specifications improved the shear capacity of the cracked interface by a factor of 1.78.”

In its report, WJE also stated: “The axial capacities of the roughened specimens … are substantially greater than the calculated axial force in Member 11 at the time of the collapse. … If the construction joint were roughened as required by the FDOT specifications, the collapse would not have occurred.”

Regarding the spreading of cracks across the unfinished bridge structure in the days leading up to the collapse, FIGG contends that MCM and other team members failed to inform the firm of the problem’s scope and severity.

On this matter, the NTSB mentioned both the engineer and contractor: “The rate of premature concrete distress was clear evidence that the structure was progressing toward failure and should have alerted FIGG Bridge Engineers and MCM to the origin of the distress mechanism that was causing the cracking and the rapidity of cracking progression.”

The NTSB is scheduled to issue its final report on the bridge collapse soon.