Ronald O. Hamburger Named Legacy Award Winner for Northern California

Pilot Hamburger occasionally flies himself to business meetings to add enjoyment to his travels.

ALL PHOTOS COURTESY OF RONALD O. HAMBURGER

Engineers who led the post- Northridge steel-connection project, from left, Malley, Steve Mahin, Ed Huston, Marc Saunders and Hamburger.

Much of Hamburger’s work has been inspecting building damage after earthquakes.

Through building code development, “we are seeking the truth to have a positive impact on society.” —Ronald O. Hamburger, Chairman and Senior Principal, SGH

Hamburger calls his post-9/11 wanted poster, circa 2002, “a stitch.”

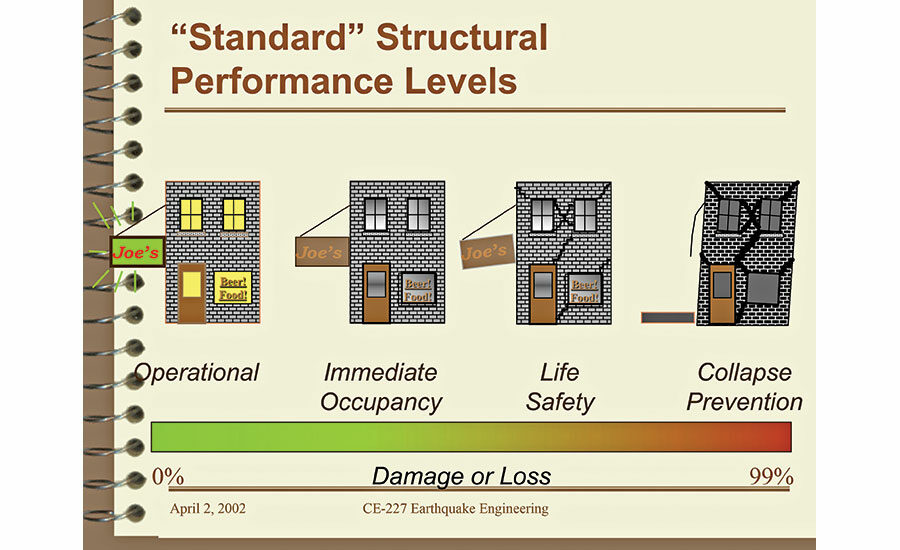

He developed sketches of Joe’s Bar to add levity to the serious subject of four standard design goals for structural performance in an earthquake.

Thirty years ago in Seattle, at the end of a talk to fellow structural engineers about lessons learned from recent earthquakes, Ronald O. Hamburger showed a photograph of a largely intact San Francisco after 1989’s magnitude-6.9 Loma Prieta quake. He followed with a photo of the utter devastation caused by 1988’s magnitude 6.8 Spitak quake in Armenia.

In Loma Prieta, there were not too many building collapses and only 63 deaths. In Armenia, years behind California in seismic design rules, there were collapses nearly everywhere and 25,000 to 50,000 deaths.

“The effect of modern construction and codes is evident from comparison of these two events,” Hamburger, currently chairman and senior principal of Simpson Gumpertz & Heger, recalls telling his audience in 1990.

Then came the Hamburger bombshell. “My belief is that Seattle lies somewhere between these two examples in preparedness,” he said.

As he tells it, Hamburger was almost “mobbed” by a number of Seattle engineers, now mostly friends, who took great offense at his having insulted their engineering capabilities. “My remarks were made [only because] Washington permitted the use of unreinforced masonry well into the 1960s,” he explains. “California had banned URM in the 1930s. Anyway, those folks had no sense of humor,” he says dismissively.

Deadpan Delivery

The presentation was quintessential deadpan-delivery Hamburger—known to speak his mind, sometimes shock and occasionally ruffle feathers.

“He got everybody’s attention,” says John Hooper, director of earthquake engineering for Seattle-based Magnusson Klemencic Associates, whose first sighting of Hamburger was at that long-ago talk. “His demeanor can be hard to understand at first because of his unique sense of humor, but he has integrity beyond reproach and doesn’t suffer fools gladly,” says Hooper.

Since then, Hamburger has gotten and kept the attention—and respect—of Hooper and an admiring cadre of competing structural engineers, working together mostly pro bono on initiatives.

“Ron is an extreme example of the many engineers who have given back to the profession in terms of volunteer work and/or leadership in engineering associations, on code committees and on research and development projects,” says Jon A. Heintz, executive director of the Applied Technology Council, which funds research.

Hamburger has led or been involved with many significant projects that have “fundamentally shaped the future of engineering practice,” he adds. “We owe him a great debt of gratitude.”

Hamburger characteristically bellows with laughter at the suggestion that, to some, the subject of codes and standards is a big yawn. He asserts that code development, to which he has dedicated his life, “isn’t boring. We are seeking the truth to have a positive impact on society [by] trying to prescribe economic, safe and reliable structures.”

With more than 40 years of experience in design, construction, education, research, evaluation, investigation and the repair of commercial, institutional and industrial facilities, Hamburger, based in San Francisco, is an internationally recognized expert in performance-based structural, earthquake and blast engineering.

“Ron is a natural leader and a visionary,” says Susan Dowty, government relations manager for the International Code Council.

Wanted Poster

Following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York City, Hamburger served as lead investigator into the destruction of the 110-story twin towers of the World Trade Center on behalf of the Structural Engineering Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE/SEI) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). For that, he earned the dubious distinction of having been listed as one of the 10 most wanted humans for crimes against humanity by one of the 9/11 conspiracy groups. Though never threatened, he came across his wanted poster on the internet, circa 2002. “I thought it was a stitch,” he says.

Hamburger is a past chair of the Structural Engineering Certification Board, a past president of the National Council of Structural Engineers Associations, a past president and fellow of the Structural Engineers Association of California and the Structural Engineers Association of Northern California, and a past director and vice president of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute. Also, he is a member of the National Academy of Engineering.

Hamburger was an ENR Newsmaker twice. Both recognitions were related to 1994’s magnitude-6.7 Northridge quake, in California, which nearly dealt a death blow to steel moment-resisting frames by fracturing welded connections—and major design assumptions—in tall buildings.

Hamburger, then working for the now-defunct seismic consultant EQE International, helped clean up the analytical mess left by the fractured connections by distilling research, conducted by a large consortium of academics and consultants across the U.S., into a unified set of guidelines.

“Ron was tireless, making sure the documents reflected our learning and were consistent,” says James Malley, a senior principal with Degenkolb Engineers, who led the research for the multi-year project.

After Northridge, building codes were altered to require testing—which could be expensive and time consuming—of each different steel moment connection in a building. In response, Hamburger led the effort to develop prequalified seismic connections.

Hamburger is proud of the post-Northridge work. But he says his most important, and favorite, project involved the development of documents that led to performance-based seismic design standards. “I played a pivotal role in that landmark project,” he says.

Change Agent

Engineers call him a change agent. The steel connection project changed the way structures are designed, detailed, fabricated, erected and inspected, says Duane Miller, manager, engineering services, at Lincoln Electric Co. And Hamburger’s “forward thinking on performance-based design was pioneering,” Miller adds.

Hamburger is known for boiling down hard concepts to simple ideas—with humor. One example is his well-circulated sketch of Joe’s Bar, showing four different design levels of building performance in a quake.

Rendering things less complicated for designers is his goal as chair of the committee updating ASCE/SEI’s Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures: ASCE 7-22. The aim is to simplify the standard from the user’s perspective while assuring it remains state of the art. He had the same goal as chair of the update of ASCE 7-16.

Jim Rossberg, ASCE’s managing director for engineering programs, is impressed with Hamburger’s vast design experience. “He is reasonable and open to discussion, though once he gets locked into a position it is hard to move him,” says Rossberg. Bob Bachman, principal of Robert E. Bachman Consulting Engineer, agrees, adding, on committee work, “when you are butting heads with Ron, you had better be prepared.”

Retired SGH chairman and CEO Glenn R. Bell, who hired Hamburger in 2002, recommended him as his successor as chairman. “Ron is a consensus builder without being a politician,” says Bell.

Hamburger has been chairman for a year, in addition to his other duties. He works 70 to 80 hours a week to keep up with his many projects. Of a normal 40 hour week, 70% of his time is billable and 30% is charged to overhead, including committee work.

Mr. Fix-It

An apt moniker for Hamburger is Mr. Fix-it. Much of his repair work has been difficult, but the list-topper is the scheme to fix the 645-ft-tall sinking Millennium Tower in San Francisco.

“Probably in terms of pure size, the level of review and the complexity of the analyses we did, this would have to be my most challenging project,” says Hamburger. The expected 22 months of remedial work by the Shimmick division of AECOM won’t begin until the involved parties agree on the final terms for payment, he says.

Most other tricky repair schemes are related to quake damage. One project involved Guam Hilton’s seven-story wing, badly damaged in a 1993 quake near Guam in Micronesia. Hamburger saved the wing, despite another engineer’s assessment it had to be razed.

Hamburger also saved the now-shuttered Broadway store at Topanga Plaza Mall, in Canoga Park—a three-story, reinforced masonry structure, with precast concrete floors, damaged in the Northridge quake. Four concrete columns partially failed in the central escalator core, allowing the middle of the second floor to drop about 2 ft. “I jacked the floor back into position, installed new columns and repaired other damage,” says Hamburger.

The Emporium Capwell store in San Francisco, housed in a historic seven-story unreinforced masonry building, experienced extensive damage, including a partial interior collapse, during the Oct. 17, 1989, Loma Prieta quake. “We worked 24 hours a day, with a contractor, to get the building back in service by Thanksgiving,” in time for Christmas sales, says Hamburger.

Loma Prieta also seriously damaged the two 15-story Pacific Bell buildings in Oakland, Calif., which housed the main interchange, including Bay Area long distance service, between Pac Bell and AT&T. Over a weekend, Hamburger designed shoring for the buildings and got them back in service. Then over two years, he designed a repair and seismic upgrade. Work had to be done while the buildings remained in service, “which was quite challenging,” says Hamburger.

Pilot, Hunter, Fisherman, Equestrian

Somehow, in addition to all his professional duties and committee work, Hamburger finds time to be a pilot, a hunter, a fisherman, an equestrian, a pianist and a karate enthusiast. On occasion, he flies his small plane for business because it saves time and offers him more control of his schedule, compared with commercial travel. “I just start the engine and go,” he says. “The cost is usually competitive to economy fares and I get to do something I enjoy while working.”

But flying isn’t always fun. Hamburger recalls a night flight 10 years ago, when he was flying with his late wife, Deborah, from the Bay Area to Salem, Ore., to visit their daughter. Preparing to land, he switched radio frequencies to the local air traffic control tower and had a complete electrical power failure, which kept him from bringing up the lights on the air field. “Luckily, someone else was landing and lit up the runway,” says Hamburger. He landed safely but recalls the incident as the most harrowing five minutes of his life.

Hamburger, 67, is looking forward to more time in pursuit of his flying, however risky, and his myriad other interests. “I’m actually hoping that 2020 will be my last year working full time,” he says.

Confident that as he winds down, others will pick up the pro bono code and standards work, he adds, “I think the engineering profession will be just fine.”