A Double-Decker Road Runs Through Vista Tower, Chicago's Third-Tallest Building

Measuring from false grade, Vista has a 17-ft-tall opening for a pedestrian path and vehicle drop-off area at the base of the middle tower. Columns continue to true grade, making the restaurant space appear to stand on stilts.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JEFF YODERS/ENR

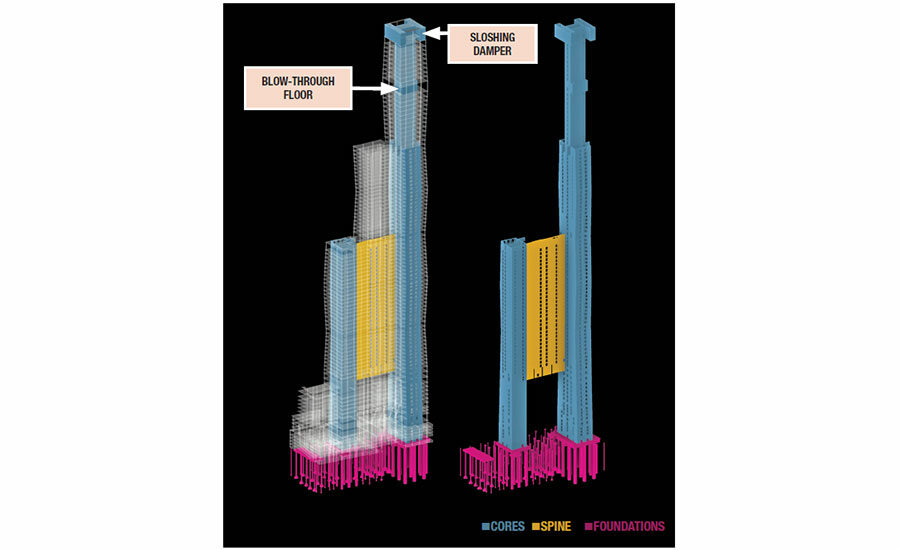

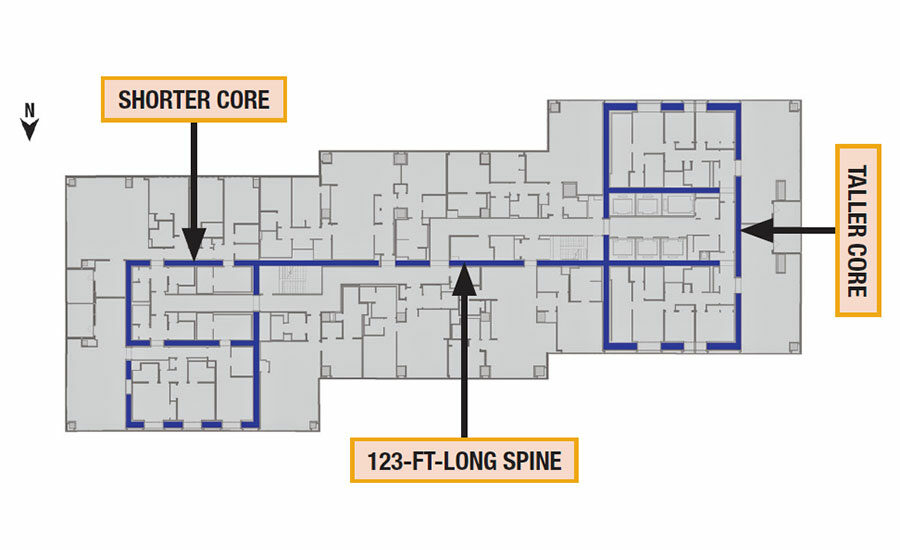

To resist wind forces, MKA designed a coupled dualcore assembly (drawing, far right). The assembly consists of a 123-ft-long, 508-ft-tall shear wall (yellow) that bears on gravity columns (white) and connects the two conventional cores (blue) in the bundled tower building.

3D Model by MKA

Vista’s three tied towers have offset footprints. The shorter core in the 51-story tower has two cells. The taller core in the 101-story tower has three cells. The middle tower has a spine wall (blue), 123 ft long, that connects the cores, forming the coupled dualcore assembly that resists lateral loads.

FLOORPLAN DIAGRAM AND 3D MODELS COURTESY OF MKA

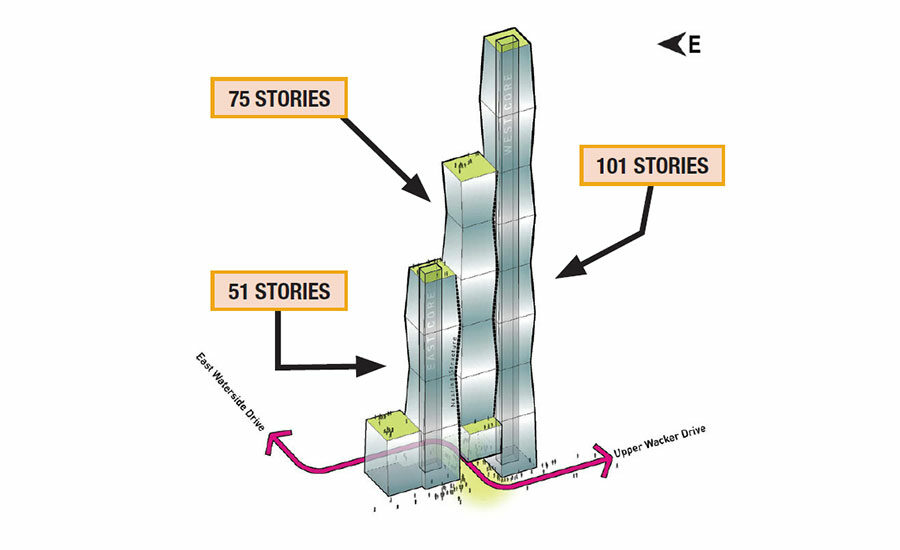

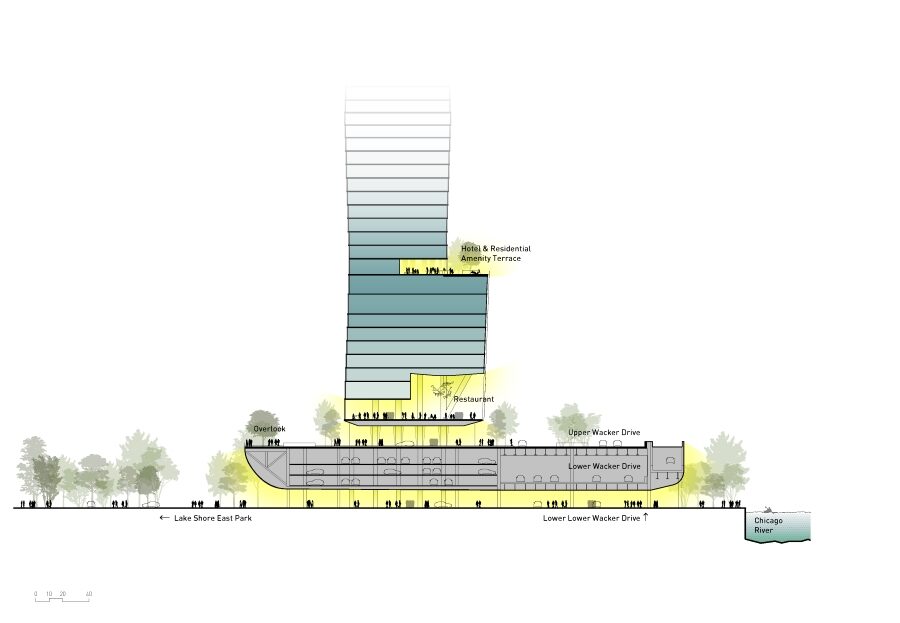

Both Upper Wacker Drive and East Waterside Drive currently dead-end near Vista’s site. When the tower is completed, a new pedestrian and vehicle connection will unite the two streets under Vista’s middle tower.

Axonometric Model Courtesy of Studio Gang

By selecting a thermal performance-rated glass, and subtle changes of color with it, Studio Gang found another way to highlight the building’s curves.

PHOTO BY NADINE POST/ENR

There’s an existing double-decker boulevard under it. An extended double-decker drive runs in front of it. There are buildings to either side. And an existing park abuts it on its fourth face.

To say that Chicago’s 1,191-ft-tall Vista Tower is squeezed into its surroundings is an understatement. The dense urban setting posed challenges for the team building the 101-story supertall.

Vista is “blocked in” on all sides, says Joel Kuna, a vice president for the general contractor, James McHugh Construction Co.

Construction started in August 2016. McHugh topped out Vista last April, making it the city’s third-tallest tower, after the 1,729-ft Willis Tower and the 1,389-ft Trump International Hotel and Tower. The building is scheduled to open in early summer.

Well before construction, it was clear that the biggest disrupter would be Field Boulevard that cuts the 52,076-sq-ft footprint in two at the base. That forced some structural gymnastics for the building, which is three stepped towers in one.

The good news for the building team was more laydown space at true grade on Lower Wacker. The bad news was that the slicing street ruled out a conventional reinforced concrete shear-wall core in the 75-story middle tower. That complicated the triple tower’s lateral-load resisting system.

“There’s a unique geometry” of three towers of stacked frustums.

– David Eckmann, Managing Principal, MKA

Instead of a three-core system to resist the city’s high winds, the structural engineer designed a coupled dual-core shear-wall assembly that connects the three buildings for wind resistance. The two outer cores are tied together via a 508-ft-tall reinforced concrete spine, from floors 15 to 51 above the upper street grade. For gravity loads, columns that continue to foundations—some located between lanes of traffic—support the 123-ft-long spine wall.

The 2-ft-thick spine transfers wind loads from the middle tower to the cores of the 51-story tower to the east and the 101-story tower to the west. The spine is “simply a mechanism we use to tie the individual cores together so they behave as one,” says David Eckmann, the managing principal of the Chicago office of structural engineer Magnusson Klemencic Associates (MKA).

Designed by Studio Gang with architect-of-record bKL Architecture for Magellan Development Group, the 1.9-million-sq-ft Vista resembles three human figures standing in a row, perhaps watching the boats go by on the Chicago River across Wacker Drive immediately to the north.

The form of each figure, or tied tower, is based on stacked truncated pyramids called frustums. The frustums, each 12 or 13 stories, complicated column lines.

“There is a unique geometry,” Eckmann says.

The frustums create tension and compression slab forces that are resolved within the reinforced concrete structure, which has post-tensioned floor slabs, says MKA.

Chicago’s two-level road system, which creates a false grade, also confuses matters, including floor numbering. The upper level of Wacker Drive along the building’s north face and the Lakeshore East neighborhood abutting Vista to its south appear to be at grade. They are not. The main entrances of all the buildings on the two-level road system are at the false grade, which is the upper street level. The lower level, which is at true grade, serves through-traffic and delivery trucks.

The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat recognizes the floor heights of the towers, at true grade, as 51 stories, 75 stories and 101 stories. But the floor numbers in the stacking plan start above the five-level parking garage, which starts at true grade.

In the stacking plan, counting from false grade, the spine runs from floor 11 to 47. A hotel will occupy levels one through 11 from false grade. Condominium residences top the hotel until level 93.

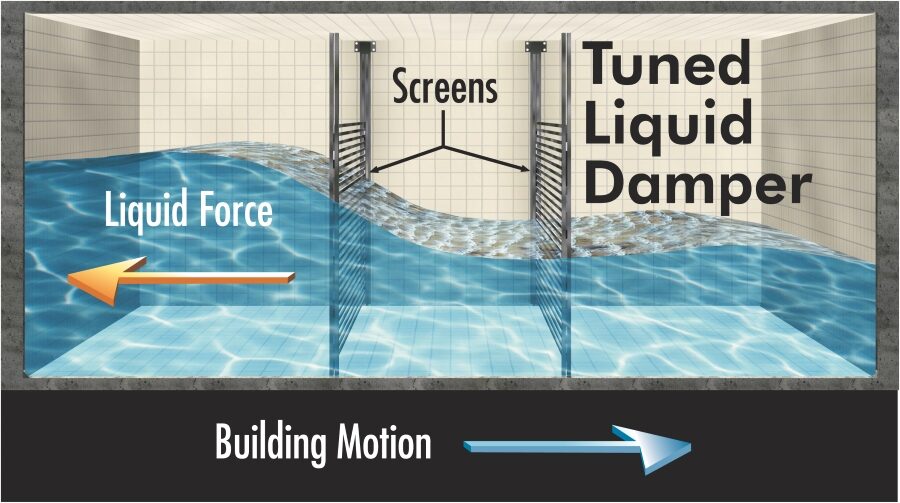

Mechanical space and damping to control sway are above that. An open-to-the-air “blow-through” floor, which lets the wind pass through the building to reduce vortex shedding, takes up levels 83 and 84.

The footprints of the three towers are slightly offset. The core in the tallest tower has three cells. North and south core walls align with perimeter walls. The core in the shortest tower has two cells. Only the north core wall aligns with the perimeter wall.

Vista has a building height-to-core aspect ratio of 40-to-1. A normal tower is about 12-to-1, Eckmann says.

The concrete walls that form the multi-celled core of the tallest tower, on the west end of Vista, range from 64 in. thick at the base to 18 in. at the top. The outermost core walls of the west core slope to follow the profile of the stacked frustum shape. A similar multi-cell core system is used in the east core. However, this core has 24-in.-thick walls and only has one additional cell, which extends to the south. The southernmost core wall slopes to follow the stacked frustum profile, similar to the perimeter walls of the west core.

The skyscraper, proximal to Lake Michigan, sits on marshy fill, necessitating deep foundations. In 1871, the remnants of the Great Chicago Fire were dumped into the lake and sediment build-up expanded the city to its east from Michigan Avenue, which is west of Vista, running north-south.

Vista’s columns are supported on deep foundations. Vista has 124 drilled piers, 24 of which are 8 ft or 10 ft in diameter and extend approximately 115 ft below grade, where they are socketed 6 ft into bedrock.

The remaining foundations are belled caissons that extend approximately 85 ft below grade. The bottom of the belled caissons are “flared” in a layer of stiff clay to increase the bearing area and capacity of the caisson.

Two concrete mats, one under each core, distribute the weight of the cores to the foundations below. The short tower’s mat is 8 ft thick and the tallest tower’s is 10 ft thick.

Crews placed a 7,000 psi self-consolidating concrete mix for the mats. The tall tower’s mat required 3,560 cu yd of concrete and took 10 hours to complete the placement.

Concrete Solutions

Vista is part of Magellan’s Lakeshore East neighborhood. Several of the early buildings in the development have post-tensioned concrete floor slabs.

McHugh, which has considerable experience with post-tensioned slabs, self-performed concrete work on Vista, as it often does. The company’s portfolio in Chicago includes the 61-story Marina City, the 98-story Trump International Hotel and Tower and the 82-story Aqua Tower, which, like Vista, faces the Lakeshore East park.

For Vista, Magellan reunited the main players in the Aqua team, including Studio Gang, MKA and McHugh.

Within each frustum, Vista’s floorplates vary from 80 ft squares to 90 ft squares. Thanks to the curves created by the changing floorplate, perimeter columns could not be vertical without interfering with the condo layouts and the views.

The different shades of glass create a visually interesting quality that further enhances and brings out the human-like shapes of the three towers.

– Juliane Wolf, Partner/Design Principal, Studio Gang

MKA considered sloping columns, but determined that “shifting” each column line slightly to follow the profile of the frustum would be more constructible and economical than sloping columns.

“We could have cantilevered the slabs at the perimeter to keep the column [lines truly vertical], but then you would still have a column through your living room in some units,” says Eckmann. Instead, “we stepped the perimeter columns 5 inches at each floor to generally follow the shape of the frustum,” he explains.

From a structural and visual standpoint, that effectively creates a sloping column line. But there are vertical columns within each story. The solution satisfied McHugh, which didn’t want to build more-complex sloping columns, says Eckmann.

To accommodate winds, the designers specified Chicago’s first blow-through floor. A double-height blow-through floor has no curtain wall and allows the wind to pass through the building rather than go around it.

“We had to pull all the stops because the building is so tall and slender,” says Eckmann.

“We needed stiffness from the concrete and sloshing dampers to manage accelerations, and a blow-through floor to reduce wind pressures,” he adds.

Vista has six sloshing dampers holding more than 400,000 gallons of water. Two sloshing dampers are on the blow-through floor and the remaining four are on the 97th and 99th floors.

Three-day Floor Cycle

After completing the parking garage and lower portions of the project, McHugh began the occupied portions of the superstructure on a three-day-per floor cycle.

Crews built the short tower, the farthest east, first. They followed with half of the tallest tower. Next came the middle tower.

McHugh had to be able to walk on a floor approximately three hours after concrete was placed in to keep up with layout work, column forming and floor forming for the next level. Placing rebar, post-tensioning elements, structural steel members and hardware for anchoring the curtain wall followed the next day.

For the floors, McHugh used a self-climbing placing tower with a trailer pump on the ground level to place the floors. Floor-forming concrete was pumped through one vertical pipe the height of each tower. Concrete for the columns and shear walls was delivered in buckets by the tower crane to eliminate the possibility of confusing it with the concrete for the floors.

The requirement for the highest modulus of elasticity concrete mix on the project is 7 million psi as an average, with nothing below 6.3 million psi. “We were just as concerned about stiffness as we were about strength,” says Eckmann.

McHugh was able to keep up its three-day-per-floor pace from the start of construction for a year and a half. The bitter cold winter of 2018 caused a delay of at least a month. For safety reasons, work could not proceed when winds off Lake Michigan reached up to 90 mph.

McHugh was still able to top the structure out in April 2019, putting it on schedule for completion later this year, Kuna says.

The frustums inspired Studio Gang to explore new glass. The units in the wider portions of the building have different thermal performance than the units in the narrower portions, says Juliane Wolf, a Studio Gang design principal and partner.

“The wider areas in the figures’ shoulders [the wider areas of the frustums], essentially heat up more slowly,” she said. “We wanted to select a glass that would mitigate that condition and be tuned to the space rather than have one uniform glass.”

The architect specified different glass shades for visual impact. The waist areas have darker glass and the shoulder areas lighter glass, which brings out the human shape of the figures, Wolf says.

Studio Gang had difficulty finding a supplier of thermal-rated glass in different shades. German supplier AGC Interpane, which ultimately supplied the glass, offers a “coating on demand” service which, via a calibrated rendering screen, allows architects to select the color of glass required together with the performance values required.

AGC Interpane’s coating line can produce the required glass overnight. “We went over to Germany and selected the colors we wanted,” says Wolf. By the next morning, “when we returned to the plant, they had produced a mock-up for us.”

“Studio Gang: Architecture,” the first monograph from the Chicago-based architecture firm, will be released in May. It explores 25 of the firm’s signature projects over its first 20 years.