Government

EPA's Rollback of Rules Faces Senate Committee Scrutiny

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Chief Andrew Wheeler faced criticism and praise from senators at a May 20 oversight hearing over a slew of rollbacks and regulations the agency has implemented since the beginning of the year.

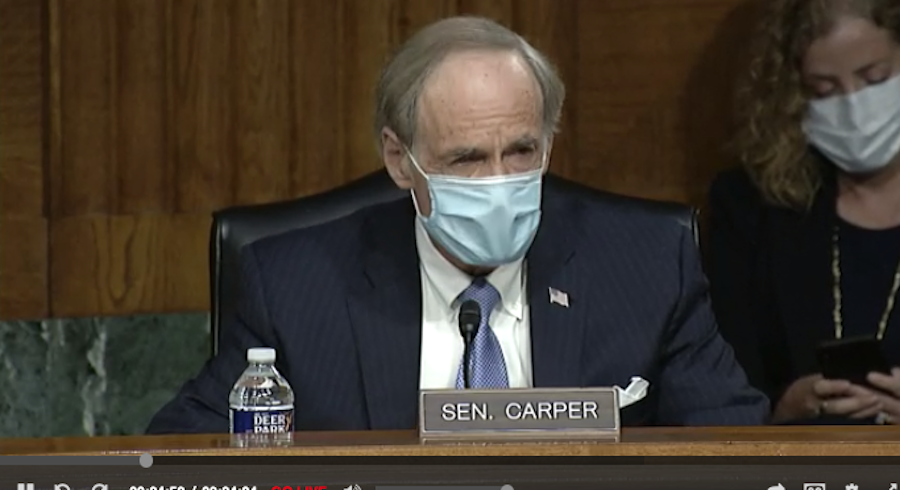

Wheeler faced members of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee who were wearing masks or questioned him remotely from their chambers. Wheeler himself did not wear a mask.

Over the last year, EPA has released proposed and final regulations—including the finalized Navigable Waters Protection Rule, the Affordable Clean Energy Rule and the Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient Vehicle Rule—all of which Democrats and environmentalists have said were rollbacks of more-stringent rules.

The agency also has proposed revisions to the Lead and Copper Rule and has taken steps to address per- and polyfluoralkyl substances (PFAS) pollution through its PFAS action plan, and recently proposed regulatory determinations for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water.

Additionally, on March 26, EPA announced it would temporarily relax enforcement of some requirements on powerplants, water utilities and other facilities in response to COVID-19.

Ranking member Tom Carper (D-Del.) pointed to a recent Harvard University study that suggested that people with pre-existing conditions who live in areas with higher levels of air pollution are more likely to die or have serious complications from COVID-19.

“We are in a fight for our lives right now. What we need is an EPA that harnesses all of its resources to help us better understand any links between air pollution and COVID-19 risks and take steps to address them. Instead, what we have is an agency taking actions that will increase air pollution and put public health at even greater risk.”

Sen. Ed Markey, (D-Mass.) said, “You owe an apology to the American people. Shame on you.”

Wheeler said the enforcement leniency applies only to monitoring and recordkeeping for small facilities, which, because of COVID-19 are unable to complete routine reports. They eventually will have to file those reports, he said. “No one is allowed to increase emissions. No one is off the hook,” he said.

Since March 16, EPA has opened 52 criminal enforcement cases, 122 civil actions and charged 10 defendants, he noted.

Committee Chairman John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.) and Wheeler attempted to discredit the Harvard study, noting that it was not peer reviewed and had other “problematic” issues.

Barrasso said overall, EPA has saved more than $5 billion in regulatory costs under the Trump administration and saved Americans an estimated $1.5 billion through deregulatory actions. He said saving American taxpayers is crucial at a time of economic crisis. “EPA is taking actions to carry out its core mission of protecting public health and the environment, while supporting economic growth. We can—and must—do both,” he said.

Other Democrats expressed frustration with EPA’s approach to cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay. They said the attorneys general of Maryland, the District of Columbia and Virginia, along with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and other environmental groups, announced on May 18 their plans to sue the agency over its lack of enforcement of Pennsylvania and New York’s share of the Chesapeake Bay plan.

Sen. Ben Cardin, a Maryland Democrat, asked Wheeler for assurance that the agency would enforce the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) water-quality requirements that each state is required to meet as part of the plan.

Wheeler said the TMDL is not legally binding, and therefore not legally “enforceable,” but that “we continue to use our other authorities,” such as permitting, to ensure states meet water-quality goals. He said the lawsuits, if filed, would ultimately harm efforts to clean up the bay.

“These lawsuits are premature at best, but [will also] pull staff from technical assistance [for] fighting frivolous lawsuits,” he added, noting that EPA staff are already working with states that are having problems meeting nutrient-reduction requirements and that the agency plans to award $6 million in funding for nitrogen-reduction projects in targeted states, “mostly Pennsylvania.”