Race Rises as a Top Construction Industry Issue After Protests

George Floyd’s death has highlighted systemic racism in many areas of society. Here protesters march in Seattle on June 12.

PHOTO: PPI/ZUMA PRESS/NEWSCOM

A lawsuit filed June 2 by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission against San Antonio, Texas-based general contractor CCC Group claiming white supervisors and co-workers bullied and threatened Black workers and used racial slurs at a jobsite in Albany County, N.Y., underlined a hard truth: Racism still occurs in construction and related fields.

Black leaders in the industry told ENR that the death of George Floyd on May 25 at the hands of police and subsequent protests appear to have opened the door to more frank discussions, not just about generic diversity and inclusion in the construction workforce, but about meaningful opportunities for change for Black employees and entrepreneurs.

“We’re at a point where the country is trying to figure out what change is going to look like,” says Wendell R. Stemley, National Association of Minority Contractors emeritus national director and founder and CEO of Black IPO Inc. “What can we do as far as solutions?” he asks.

“We’re at a point where the country is trying to figure out what change is going to look like. What can we do as far as solutions?”

– Wendell R. Stemley, National Association of Minority Contractors Emeritus National Director

While the incidents alleged in the CCC incident are overt, Black leaders say they more often see an underlying systemic racism that disadvantages Black workers in everything from training opportunities to reaching the C-Suite.

“We are at a seminal moment,” says Michael Brown, executive vice president at Skanska USA, who is Black. “We’re seeing an awakening to the fact that systemic racism still exists in our society. I’ve had conversations in the past two weeks that I haven’t had in 54 years.”

Skanska and numerous other companies, as well as industry groups, are working to tackle issues such as unconscious bias and to increase training opportunities.

“I have asked each member of the Turner community—all 10,000 people—to commit, not passively, that this will be the most important thing they will do in their entire careers. If we don’t build another building, and we do this right, it will be for the future generations of Turner and for our sustainability in the industry,” says Peter Davoren, CEO of the national contractor. “There will be no more silence.”

Working harder for a more diverse workforce isn’t just a practical matter. For industry members who see the need, it’s a moral imperative. Racism “is something that people shouldn’t be afraid to discuss,” says Michael B. Russell, CEO of H.J. Russell & Co., a large, Atlanta-based Black-owned contractor founded in 1952. “Silence means you’re complicit with where we are today. If you really care about things getting better, you have to be willing to step up and speak up. That’s my message.”

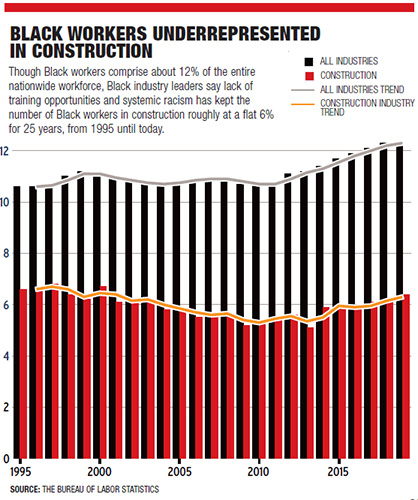

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics says that while Black people comprise 12% of the workforce, they make up just 6% of the workforce in construction—numbers that have been relatively unchanged for 25 years.

“This is an issue—too long an issue in the industry. We still need to have the conversation,” says Jumoke Akin-Taylor, a veteran Black project manager for the city and county of San Francisco, with more than 30 years in working in the construction sector.

“The flip side of this moment is opportunity,” says Ron Lewis, executive director of design, engineering and construction management at Seattle’s Sound Transit, who also is Black. “I think there’s a growing awareness and interest of what systemic racism looks like. People across a broad spectrum are willing to engage, but many of them don’t know how.”

Unconscious Bias

Lewis adds, “It’s important at a leadership level to acknowledge institutional racism—understanding what that means. Leaders need to model the way. If you see something that’s not right as a leader, everyone’s watching. You’ve got to have the courage to step in.”

“I had to work very hard and push beyond and try not to make mistakes. If I did, the consequences for me would be different than for someone else.”

– Toks Omishakin, Director, California Dept. of Transportation

The EEOC complaint in the New York case alleges that white supervisors and coworkers commented that Black workers on the cement plant modernization project, which completed in 2017, were better suited for menial labor that required less skill and intelligence.

Project contractor CCC Group denies the allegations made in the complaint and says its management was not made aware of any incidents until after the project was over.

President and CEO Joe A. Garza says the company could not substantiate any of the claims made in the complaint and that such conduct is not tolerated or allowed at the firm. The lawsuit seeks a permanent injunction against CCC Group and new policies and practices at the company to protect employees from hostile working conditions. It also requests punitive damages for Black workers.

Whether or not the claim against CCC is found to have merit, sources referred to less obvious slights that may or may not have been intentional.

“Unconscious bias is the most challenging thing. People don’t hate me because I’m Black or a woman. They just can’t understand that I’m on par with them,” says Akin-Taylor. After a recent detailed presentation on design-build, she was questioned about her accuracy. “It’s not direct racism, but having others not believing you know what you’re saying is the biggest problem for people like me,” she says. “You’re there as a token, an EEO symbol.”

Others recount stories of establishing relationships by phone or email that turn cold when someone meets them in person and finds out they are Black. “I still [see shock expressions] when I arrive on site and they realize Adrian Russell is a Black guy,” says Adrian Russell, a project manager at Mattcon General Contractors. “What I experience is something that is unmistakable. You’ve been conversing by email for weeks, you’re almost friends with this guy. The guy who has been so friendly and so outgoing for a month, once he sees you … there’s almost a wall, an icy tension. It doesn’t happen all the time, but …”

Russell adds, “You learn to manage. I have friends who are professional individuals, who are angry and struggling with what’s going on in this country. At the same time, they’re terrified to express that to their coworkers and bosses. On weekends you can be one person, but when you report to the office you have to pretend these problems don’t exist.”

“Where the divide exists, is that people are comfortable in their own space, and it’s very uncomfortable to have conversations about areas or things that are different.”

– Gloria Samuel, VP of Retail Construction, Fifth Third Bank in Cincinnati

Those who have succeeded note the extra struggle. “I had to work very hard and push beyond and try not to make mistakes,” says Toks Omishakin, director of the California Dept. of Transportation, who is Black. “If I did, the consequences for me would be different than for someone else.” He has encountered issues such as being excluded from meetings where he could have had input, but says, “to me, it just meant going back and getting stronger.”

Even something as benign as office banter and activities outside of work can be a barrier, says Gloria Samuel, a vice president of retail construction at Fifth Third Bank in Cincinnati, who is Black. She worked for 17 years as a construction executive at Messer Construction.

“Groups in the office might say, ‘Hey, let’s go canoeing.’ Well, most of the time, their Black peers may not have ever done that or may not have ever experienced that. Where the divide still exists is that people are comfortable in their own space, and it’s very uncomfortable to have conversations about areas or things that are different,” Samuel says.

The Associated General Contractors of America recently launched Culture of CARE, a program designed to boost industry inclusiveness and diversity. The group says 100 member companies so far have signed the pledge promising to “commit, attract, retain and empower” employees.

“We’re asking companies to commit to hire based on skill and experience, regardless of ethnicity, gender, race, nationality, religion or sexual orientation," says Brynn Huneke, AGC director of diversity and inclusion and member engagement. "The aim is to attract prospective employees by creating workplaces and cultures that are free from harassment, hazing and bullying; to retain high-performing employees by identifying and removing barriers to advancement; and then empower every employee to promote a culture of diversity and inclusion—or a culture of care—within their companies.”

The recent Black Lives Matter protests acted as an accelerator for the National Black Contractors Association and the AGC San Diego chapter to sign a memorandum of agreement that will increase the scope of training and hiring programs, especially on larger projects, for Black workers in the area. The discussion of such a program had predated the recent protests.

Lack of Opportunities

There’s wide agreement that more needs to be done to provide opportunities for Black workers in the construction workforce. “We need to get good quality people, and the industry needs to continue to do a better job to reach out to more diverse audiences and find a way to make the industry more inviting for diverse people,” says contractor executive Michael Russell.

Scott Shelar, president and CEO of the Construction Education Foundation of Georgia, thinks more cities across the country should have programs targeted to Black workers. He points to Atlanta’s Construction Ready program, which was started in 2014 as a way to train at-risk youth. “The top of the funnel has to be bigger,” he says. “And the only way you make the top of the funnel bigger is to reach out to groups of people that we haven’t reached out to before.”

“The flip side of this moment is opportunity. … I think there’s a growing awareness and interest. People from a broad spectrum are willing to engage.”

– Ron Lewis, Executive Director of Design, Engineering and Construction Management, Seattle Sound Transit

Paul King, a former Chicago subcontractor and an industry activist since the 1970s working to promote more Blacks in trade, professional and entrepreneurial ranks, also faults “the failure of vocational training” to make construction a career path. He says high school and community college programs are not “targeting African American students.”

King also notes the large number of Black men in prison who are unaware of industry opportunities. “If there was more training for them, they could be craft workers when they get out,” he says. “They’re a captive audience so that would create a pipeline to bring more young Blacks into construction.”

One success story he points to is the St. Paul Community Development Ministries Inc., a church-affiliated pre-apprentice program run by Kevin Ford, a Black pastor who recruits from Chicago’s south side. Now in its second decade, the program is working to remove barriers to entry into union apprentice programs that also include a “broken education system that has students failing in basic math and reading comprehension,” he says.

Some 223 students, mostly Black males, have come through the program, says Ford. “This is where the excitement comes in” he says, noting that apprentice program coordinators and unions “even in polarized Chicago, have opened their doors” to its graduates. “We prepare students to overcome racism in the industry, to deal with individuals who don’t see eye to eye,” Ford says.

“This is the perfect season to bring all of humanity together,” he says. “I’m getting calls from all over. There’s a lot of scar tissue. People say it’s time to work together. We will show it in Chicago. It’s not all doom and dire.”

With Scott Lewis, Scott Judy, Jeff Yoders and Corrine Grinapol, Scott Blair and Pam Radtke Russell