Historic Landmarks

Drastic Rebuild Resurrects Graves' Landmark Portland Building

A unitized painted-metal curtain-wall system replicated the original painted concrete walls, which had leaked. A terra cotta system at the base replaced problematic mortar-set ceramic tiles.

Photography by James Ewing/JBSA

The replica of the Portland Building envelope consists of a unitized painted-metal curtain wall system on the upper floors and a teal terra cotta tile system on the base.

Photography by James Ewing/JBSA

A young Michael Graves, who died in 2015, standing near his first major commission, the Portland Building, soon after it was finished in 1982.

Photography by Peter Aaron/OTTO

Thanks to the small window openings of the building, workers had to install the new modular curtain wall system from movable work platforms outside the building rather than from the inside, which is standard.

Photo courtesy of DLR Group

For the new concrete shear wall core, workers had to cut slots in the waffle floor slab around the exiting service core. The slots allowed the shear walls of the core to be constructed from the basement to the roof.

Photo courtesy of Balfour Beatty

A section of the new shear wall core ready for concrete.

Photo courtesy Balfour Beatty

An example of the interior transformation after the gut rebuild of the Portland Building.

Photography by James Ewing/JBSA

Fifteen minutes into a 105-minute job interview for the $195-million overhaul of the long-troubled Portland Public Service Building in Oregon’s largest city, owner’s rep Mike Day threw a curve ball to the unwitting design-build team of Howard S. Wright Construction Co. and architect DLR Group. Already hard at work solving Day’s first faux crisis scenario—a budget buster that threatened the viability of the makeover of the notoriously dysfunctional landmark—they had to regroup.

Designed by the late Michael Graves and considered the building that solidified the postmodern movement in architecture, the leaking 15-story icon—colorfully whimsical on the outside but dubbed the tallest basement in the world because of its dark and dreary interiors—had persistent envelope failure problems that started five years after it opened in 1982. It also had antiquated structural and mechanical systems.

The project had “a lot of potential barriers” beyond its leaking concrete exterior walls.

– Kristin Wells, Portland Office of Management and Finance

At the June 13, 2016 interview, the curve ball started with a staged phone call to a member of the selection panel. The caller had bad news: Yet another crisis was brewing—this time a potential budget and schedule buster relating to the supply of reinforcing steel.

All three contenders for the job, which also included the Andersen/FFA /Perkins + Will DBR Team and the team of JE Dunn Construction and Yost Grube Hall Architecture—were qualified for the work. So Day devised a way to differentiate the three teams.

“We built something into all three interviews that was a little more interactive” and spontaneous than the usual canned presentations, says Day, president of Day CPM, which became a division of Otak in 2017.

All three teams were warned in advance that they would be given a problem scenario 30 minutes before the interview started. But they didn’t expect the curve ball.

“When I was in the middle of running one of the breakout sessions we had established for the ‘problem’ engagement portion of the interview, I was briefly surprised that there was a phone ringing and then immediately aware that the ‘new’ information was just another fun aspect of the problem-solving performance, mainly because the phone was answered and the new information was conveyed somewhat dramatically,” says Carla J. Weinheimer, DLR Group’s project principal.

For Kathleen Brenes-Morua, the city’s design and construction procurement services manager, the key elements of the HSW-DLR team’s performance were its collaboration skills, especially with the owner, and its ability to respond quickly to a problem.

The HSW-DLR Group team won the job, even though it “wasn’t the highest scoring team at the written stage," adds Kristin Wells, the facilities division manager in the city’s Office of Management and Finance.

Landmark Status a Challenge

Graves’s first major commission—full of color and ornamentation in contrast to the stark modern architecture movement—is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a building of “exceptional importance.” The landmark status further complicated the design-approval process, says DLR Group.

The overhaul of the postmodern landmark primarily involved fixing the envelope, upgrading the seismic resistance to current codes, replacing antiquated mechanical-electrical-plumbing (MEP) systems and gutting and remodeling the depressing interior.

"The project had a lot of moving parts and things to figure out,” says Todd Miller, vice president of operations for Balfour Beatty Construction, doing business as HSW.

Under progressive design-build delivery, “the city could stop us along the way if we were off schedule or off budget.”

– Todd Miller, Balfour Beatty Construction

That’s why Brenes-Morua, Wells and Day knew they also needed a special type of project delivery, not construction management-general contracting normally used by the city.

In 2015, based on studies of all the failing building systems, the city decided to fix the building rather than raze it. That was the signal for Brenes-Morua to research a contracting approach never before used by the city.

Called progressive design-build by the Design Build Institute of America, DBIA’s twist on conventional design-build involves progressive contracting. Under the model, the design-build team is engaged one phase at a time. If the team meets its targets for one phase, it proceeds to the next.

“The city could stop us along the way if we were off schedule or off budget,” says Miller.

The city needed—and was granted—an exemption from the state legislature to use the method. All state and city approvals were in place by the end of January 2016.

In anticipation, Brenes-Morua had already received permission from the city to first hire an owner’s rep, rather than an architect. Day CPM provided “another set of experienced eyes and ears” for the city, she says.

As the city’s manager of the all-but complete makeover, Wells knew progressive design-build was important. But it was not enough. “I felt very strongly that we needed collaborative design-build” delivery, with progressive contracting, she says.

Collaborative Design-Build

Collaborative design-build also incorporates the building team behaviors of Lean Integrated Project Delivery. "We were incentivized to succeed, truly in the spirit of IPD,” but without the multiparty agreement, says Miller.

The guaranteed maximum price was eventually set at $147.3 million. “If we were under budget, we got the opportunity to share 50% of the savings with the city, up to a certain amount,” he adds.

Scott Bevan, principal for the MEP consultant, PAE Engineers, is a big supporter of collaborative design-build because it offers a forum to allow people to do what they do best.

The hybrid delivery model worked. The project, substantially complete last December, came in “several-million dollars” under budget, says Wells.

“Collaborative design-build offers a forum to allow people to do what they do best.”

– Scott Bevan, PAE Engineers

“It was absolutely successful,” adds Brenes-Morua. “I don’t think we would have the facility we have today had it not been for the delivery strategy,” she adds.

Wells adds, “it’s a fantastic methodology if you have hurdles and know you will need to problem-solve.” For a straightforward project, “you don’t need it,” she says.

It was no secret that the makeover of the Portland Building was anything but straightforward. The project had “a lot of potential barriers” beyond its leaking concrete exterior walls, says Wells. “This could have had some really bad outcomes,” agrees Day.

Before beginning the reconstruction, HSW-DLR Group was charged with evaluating, based on cost and schedule, whether to relocate the city’s 1,300-person staff to leased space or to phase the work, which would take much longer. Based on the evaluation, the city decided to vacate the building, despite the extra costs involved, to minimize the project’s duration.

The rebuild has space for 1,600 employees. Design began in August 2016. The move-in, over 11 weekends, was just complete in March when the pandemic hit and the building closed. Since then, the staff has been working remotely.

Crews are currently scheduled to complete the final piece of the project—first floor interiors—by the end of the year.

Giant Jukebox

Labeled everything from a “giant jukebox” to a “mausoleum,” the full city-block building was the first large-scale project for Graves, who died in 2015.

“Things had not gone well from the start” of the original project, says Day.

Problems were mostly caused by the extremely low $20.7-million budget (ENR 10/9/1980 p. 16). The original design-build team—which in addition to Graves included the joint venture of Pavarini Construction Co. Inc. and Hoffman Construction Co.—was between a rock and a hard place even before it was selected.

For example, as a stipulation for winning, the team had to agree to change a proposed nonmasonry drywall façade, which was already a change from its proposed terracotta cladding, to a more durable and expensive façade, and still guarantee the $20.7-million price tag.

For this, the structural engineer, DeSimone, Chaplin & Associates, had a winning idea. It would revise the proposed structural system, which originally consisted of a relatively simple structural core combined with a moment-resisting frame and waffle slabs with integral beams.

The accepted revise, which was built, eliminated the structural core. Instead, to resist lateral loads, there is a 150-ft-square exterior reinforced concrete box, with stick-built punched windows.

The punched shear-wall exterior tube begins above the third floor, after the setbacks. Below the wall, loads are transferred by a girder to columns and carried down to a mat. The exposed concrete is coated with elastomeric paint.

The facades of the three-story base were clad in teal-colored mortar-set ceramic tile. By 1988, there was evidence of efflorescence. Then, the building started leaking around the windows. Despite repairs, the conditions worsened.

Graves' First Major Commission

Patrick Burke, a principal of Michael Graves Architecture & Design, says Graves was so “desperate” to get his first major commission that he bent over backwards to accommodate the owner’s unreasonable demands.

The experience taught Graves a lesson. He would never again take on a job with an inadequate budget, says Burke, who joined the firm in 1982.

DLR Group contacted the Graves office in 2016, to offer the firm a role on the team as a design critic. “I was really surprised how well it turned out,” says Burke, of the rebuild. “It’s a gigantic improvement.”

The city viewed the rebuild as “a second chance to get it right,” Day says.

“I was really surprised how well it turned out. It’s a gigantic improvement."

– Patrick Burke, Michael Graves Architecture & Design

For DLR Group, the most significant aesthetic design challenge was finding a way to maintain the historic integrity of the exterior architecture while meeting the project’s exterior enclosure performance goals—no water intrusion and significantly improved daylighting, thermal performance, seismic performance and pedestrian interface at the base of the building—for 50 years or more.

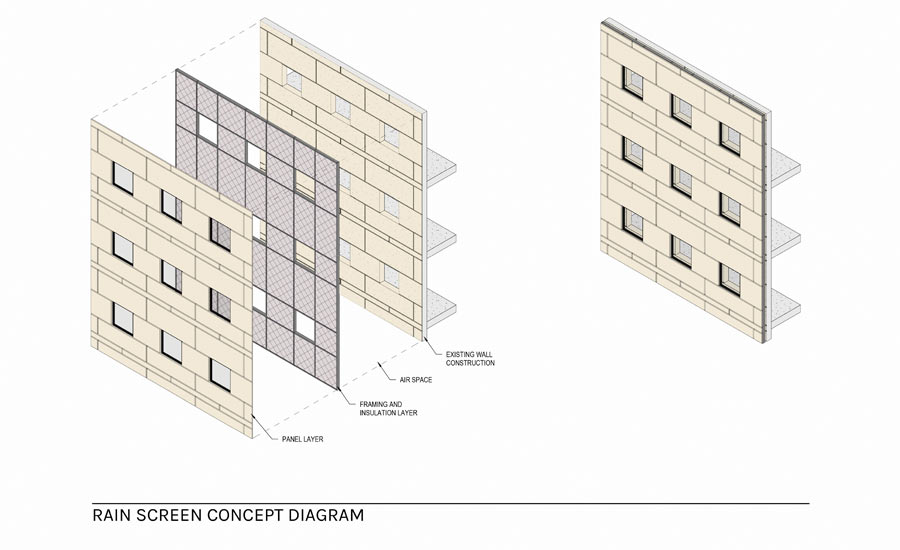

HSW-DLR Group knew it could not meet the owner's performance goals by restoring the problematic envelope, which also was not insulated and had single-pane windows, to its original inferior state. The team soon proposed overcladding the concrete walls with a unitized painted-metal curtain wall system, with a rainscreen layer. At the base, there would be terracotta tile, mechanically hung as a rainscreen system. Both would replicate the building’s forms, detailing and colors.

Potential Budget Buster

The overclad included slightly larger double-glazed clear-glass windows, not the unpopular tinted-black windows of the original, which Burke says Graves did not specify.

The cost of the overclad would be $8.8 million—a true potential budget buster. “Our proposal for the rainscreen system blew the budget by $6.5 million,” says Miller.

There was “some push back initially from strict preservationists against overcladding the face with modern curtain wall technology.”

– Jeffrey Heymann, Benson Industries Inc.

HSW-DLR Group suggested ways to slice nearly $5 million off the budget—mostly by salvaging more material and components than originally anticipated and avoiding the cost of hoists by using existing elevators and stairs. That would shave $2 million off the electrical work, $600,000 off elevator and stair costs and $2 million off demolition costs.

The city contributed the rest from its contingency fund, which it had reduced by $6.5 million “because we removed so many risks” from the project, says Miller.

The overclad moved forward, but it was a bit challenging. Unitized systems, which are prefabricated into modules, are most efficient for repetitive cladding systems. The Portland Building had different details, colors and ornaments.

Production challenges aside, there was “some push back initially from strict preservationists against overcladding the face with modern curtain wall technology,” says Jeffrey Heymann, a vice president of unitized-system supplier-installer Benson Industries Inc., which joined the team in a design-assist role.

The overclad project is viewed as both “controversial and ground breaking” in historic preservation circles, adds Erica Ceder, DLR Group’s historic preservation specialist and project architect for the exterior. The norm is either to restore a building to its original state or preserve it as it was during a certain period.

Seismic Upgrade

Meanwhile, structural consultant KPFF was working out the next biggest challenge—the seismic upgrade.

The original structure did not meet current seismic codes, which had changed drastically to reflect the likelihood of a magnitude 9.0 quake, expected since the discovery in 1970 of the Cascadia subduction zone, which runs from northern California to British Columbia, 70 to 100 miles off the Pacific Coast.

The new core is “smack in the building's center, so there is no torsion or twisting.”

– Mark Tobin, KPFF

KPFF considered either strengthening the exterior concrete shear walls or creating a shear wall core, as proposed for the original structure, around the existing 90-ft by 30-ft service core.

KPFF selected the structural core option. "It's smack in the building's center, so there is no torsion or twisting,” says Mark Tobin, a KPFF principal. The full-height core is 94 ft x 34 ft in plan. It springs from a thickened mat, approximately 109 ft x 49 ft. The mat was created by adding an additional 2 ft of thickness on top of the building’s existing 2.5-ft-thick mat.

A corridor splits the core walls into two mirror-image “square C” shapes, in plan. As the building increases in height, the core's short- direction walls vary in thickness from 28 in. to 16 in. In the long direction, they vary from 18 in. to 1 ft.

Floor diaphragms resist both inertial forces generated from quake accelerations and transfer forces generated between the existing exterior walls and the new core.

Concrete Exterior Too Stiff

The exterior concrete walls also participate in resisting seismic forces, but they were too weak to perform well, says Tobin. “We had to design the core shear walls to be stiff enough so that they could pull load away from the exterior walls to the point where the existing walls could accommodate the seismic drifts of the building,” says Tobin.

The exterior concrete walls terminate at the third floor and transfer their gravity loads to large concrete columns. That meant that any seismic shear and overturning forces in these walls must also transfer at this level, Tobin adds.

The shear transfers out through the floor diaphragm to the new core. The overturning moment is resisted by axial forces generated in the existing columns below the exterior wall. Both the floor diaphragm and the columns required strengthening to accommodate these transfer forces.

More measures were needed. Columns from the third floor down to the foundation that support the exterior walls did not have adequate capacity to resist the prescribed combined dead, live and seismic axial loads. Additionally, the columns did not meet current standards for reinforcing detailing that is meant to provide for ductile behavior during seismic loading.

KPFF’s solution was to wrap the columns with fiber-reinforced polymer both to increase their capacity and to provide ductile behavior.

The exterior walls also are load-bearing above the third floor. The gravity loads are relatively high, says Tobin.

“The tricky parts for us were the pretty high-level energy efficiency goals and LEED requirements."

– Scott Bevan, PAE Engineers

Because the walls were lightly reinforced without ductile detailing, KPFF specified new secondary columns around the perimeter of the building, directly against the inside face of the concrete walls and epoxy-doweled into the walls. The new columns provide an alternate load path to support the floor slabs, says Tobin.

The MEP systems also were antiquated. “The tricky part for us were the pretty high-level energy efficiency goals and LEED Gold requirements,” says PAE's Bevan. The building achieved LEED Platinum status this month.

For the heating, ventilating and air-conditioning (HVAC) system, “nothing was worth leveraging for use,” says Bevan. “We provided a full new mechanical plant, though the distribution shafts were saved.”

The HVAC’s heat-pump system is all electric, theoretically from renewable sources, to reduce the amount of carbon used in the building’s operation.

Relocate the Staff

One of HSW-DLR Group's first tasks was to evaluate for the city whether to relocate the staff or work around the occupied offices. The city decided to lease temporary space rather than phase construction around building occupants, which would have taken longer.

The team got its notice to proceed on Dec. 4, 2017 and reached substantial completion exactly two years later.

From a contractor’s standpoint, logistics were the key, not the individual tasks. HSW, which self-performed concrete work, used just-in-time delivery, for example, because there was little room for staging outside the building.

For construction, “the building sliced and diced pretty nicely to support” concurrent exterior and interior work, which helped reduce the schedule, says Miller.

Overclad Increased the Footprint

The overclad increased the building’s footprint by 7 in. on each face, which meant that the building went over the lot line, just slightly. To proceed with that, the team needed and received a variance from the city’s department of transportation, which is responsible for sidewalks.

A prefabricated unitized curtain wall doesn’t lend itself to the many unique conditions. But Benson and the design team produced various types of modules to replicate the many exterior colors, materials and shapes, including complex rustication patterns and dynamic ribbon elements. Of the 964 panels, one quarter are not repeated.

“We even worked with paint suppliers to find the right colors,” says Heymann.

A sample of each panel type was produced and assembled into a performance mock-up that was evaluated for fit, alignment and color before testing. Modules, prefabricated in Benson’s factory in Mexico, were then tested before and after installation.

For exterior access above the third floor, crews installed a series of motorized climbing work platforms that rode up and down the building on masts. The masts landed on the roof of the three-story base and were shored through the building. Crews on the motorized work platforms drilled 30,000 holes in the concrete wall and inserted the anchors for the curtain wall modules.

Each module was picked by a tower crane, rather than the typical way of storing panels on the building's floors and flying them into place. This outside installation was necessary because the modules, typically 10 ft wide and 12 ft tall but as wide as 25 ft, could not fit through the 4-ft-square window openings.

Crews on the climbing platforms attached each module to the building using structural clips at the end of an 18-in.-long epoxy anchor, weighing 1,500 lb.

Installing modules from outside is higher risk because of the greater potential for falling objects, says Miller. For safety’s sake, sidewalks were either protected with sidewalk sheds, closed to pedestrians or both.

The freestanding tower crane sat on the third floor extension roof and was supported through the building in the space of an existing stairwell, which was demolished from the basement to the third floor.

Existing stairs and elevators in the service core replaced materials and personnel hoists, except for a temporary exterior stair for the demolition work. The 8-ft-square elevators were used for smaller materials, which was key to keeping costs down.

The team salvaged most of the existing structure and the plumbing and piping, which also kept costs down, says Miller.

On the outside, prep work started on the north and west elevations first. When it was time to install the curtain wall modules, prep work started on the south and east elevations. The sequence was based on the preference of the curtain wall contractor, says Miller.

Terra cotta tile work on the face of the three-level extension did not begin until the work from four to 15 was done and the mast access scaffold was taken down. Workers accessed the first three levels from a rolling scaffold.

In April 2019, workers finished the curtain wall.

Core Work Messy

Inside, the critical path was getting the new core up through the fourth floor, so that interiors work could begin below it. The core work was “big and messy,” says Miller.

The sequence began with the demolition required for the thickened mat. For that, crews cut out 30% of the basement slab.

After the core hit the fourth level, the interiors work started below it. Then, that became the critical path because it was slower than the core work.

“We are currently creating a playbook, including lessons learned,” requested by Mayor Ted Wheeler.

– Kristin Wells, Portland Office of Management and Finance.

For the core walls, crews generally worked on three floors at a time, going up the tower. They started by shoring the slabs around the future wall slots. Demolition of the slab for the slots followed.

Horizontal steel dowels came next, drilled into the waffle slab along the sides of the slots, to connect the new wall to the slabs. Wall rebar followed. Then, workers placed the infill floor slab before casting the wall itself.

In lieu of the original plan for formwork, HSW opted for shotcrete against engineered drywall, which was more constructible and economical. “Using the drywall as the form allowed us to save time,” says Miller.

A standard design-build project would have required a change order for that, he adds. But KPFF designed it under its contract because the shotcrete wall became part of the permanent structure.

The square footage lost to the new walls was made up by the area gained from moving the mechanical room from the second floor to the roof, says DLR Group.

The exact amount of the “several million dollars” of savings will be calculated after construction is complete. After that, the city will decide what to do with the remaining contingency funds, says Wells.

Meanwhile she is thrilled with the way the collaborative design-build delivery played out. The city also is so pleased with the Portland Building makeover that it plans to use the delivery model on other projects.

“We are currently creating a playbook, including lessons learned,” requested by Mayor Ted Wheeler, Wells says.

“Contractors and architects think and work differently,” she adds. Aside from total owner-team engagement throughout, the “pushes and pulls” of the HSW-DLR Group team members “were the best part” of the process, Wells says. “That’s when we sang!”