Public Works

Dilemma Over Competing Ideas Pushes Back Start of Big Boston Highway Project

The $1.3-billion realignment of Boston's Mass Pike could be delayed by more than a year

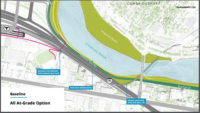

Construction on a massive, $1.3 billion realignment of a key stretch of the Massachusetts Turnpike in Boston will now be delayed by another year and possibly longer. Several stakeholders support replacing the viaduct with at-grade highway lanes (pictured above) along the river. Rendering by Perkins&Will | cbt, courtesy of A Better City

Torn between competing visions, state transportation officials say construction on a massive, $1.3 billion realignment of a key stretch of the Massachusetts Turnpike in Boston will now be delayed by another year and possibly longer.

The officials have postponed until next summer a key decision on how to proceed with the reconstruction of the turnpike in the city’s Allston neighborhood, a key chokepoint into the city for both commuter and rail traffic.

State officials are faced with the choice between two main alternatives, replacing a stretch of highway on an aging, mid-1960s viaduct in need of repair with a new span of roadway at grade along the Charles River, or simply replacing the viaduct with a new one.

That, in turn, will have a major impact on the start of construction, Stephanie Pollack, the state’s transportation chief, told board members of the Massachusetts Dept. of Transportation.

State officials are faced with the choice between two main alternatives, replacing a stretch of highway on an aging, mid-1960s viaduct in need of repair with a new span of roadway at grade along the Charles River, or simply replacing the viaduct with a new one.

Those officials indicated they see strong support among “stakeholders” and other members of the public for removing the viaduct and proceeding and replacing it with at-grade highway lanes along the river.

Supporters of the at-grade option contend it would help reconnect the city with the waterfront along the Charles, with the viaduct and the elevated stretch of Turnpike having acted for decades as a giant barrier.

But further analysis is needed, as well as a clearer plan for financing the project. The delay would also align the choice state transportation officials are calling the “preferred alternative” with the filing of key piece of required state environmental paperwork, slated for mid-2021.

“It probably delays the project by a year,” Pollack said.

That delay, in turn, would push off the launch of construction to the middle of the decade, to late 2024 to early 2025.

The design-build procurement process wouldn’t kick off until mid-2023, while the design-build process wouldn’t move forward until mid-2024.

However, state transportation officials have not ruled out the option of simply repairing the current viaduct, which Pollack calls “Plan B.”

That has advocates of a modern, at-grade highway segment concerned about the potential of an even much longer delay of a decade or more.

In discussing the repair option, Pollack noted it could extend the life of the viaduct for another 10-15 years. At the least, it would give state transportation officials a fallback should there be significant delays in the approvals and financing of the other two main options, including reconstructing the highway at-grade and getting rid of the viaduct altogether.

The at-grade plan was clearly the most popular option, with the vast majority of the more than 500 comments state transportation officials received on the issue during a public review period backing the at-grade plan.

The support was strong enough to stop state transportation officials from instead forging ahead with plans to build a new viaduct, which Pollack acknowledges is unpopular.

But rebuilding the highway at grade will also involve filling about an acre of the adjacent Charles River, which, in turn, will involve an intensive and potentially more time-consuming federal and state review process.

“We just need to have a Plan B, that would allow us to fix the viaduct and that will allow us to get through the process,” Pollack said. “I think this is the responsible thing to do. Such a near-term solution would give more time to build public consensus.

Critic Cites Cost of Delay

But Rick Dimino, president of a business-backed nonprofit, A Better City, and a long-time champion of eliminating the viaduct and rebuilding the turnpike in Allston at-grade, was critical of what he contends is an unnecessary and potentially costly delay.

Dimino said replacing the half-century-old viaduct with another one would buck decades of efforts by Boston and other cities to remove hulking highway barriers and reconnect the urban fabric of neighborhoods.

Dimino contends state transportation officials should be able to both pick the at-grade option as the preferred alternative and move ahead with financing and environmental permitting plans at the same time.

By delaying, state officials run the risk of not being prepared to take advantage of a likely infrastructure proposal from the new Biden Administration after it takes the reins in January.

“We need proactive action to position this project for a Biden infrastructure bill,” Dimino said. “It is just smart government. You want to put Massachusetts to be first in line with some really good ways to use that money.”